REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/dt10202601151251

Diego Santiago Marinho¹

Antônio Levy Carvalho Nobre¹

Vicente Bruno de Freitas Guimarães¹

Carlos Otávio de Arruda Bezerra Filho¹

Bruna Mara Machado Ribeiro2

Abstract

Mounjaro works by activating two gut hormone receptors, GIP and GLP-1, to manage blood sugar. This stimulates insulin release when glucose is high, reduces liver glucagon production, slows stomach emptying to control post-meal sugar spikes, and increases fullness to reduce appetite and food intake. Mounjaro with reported effects on central nervous system neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, and neuroprotection. Here, we investigated the potential anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of Mounjaro in primary hippocampal neuronal cultures exposed to the viral mimetic polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)). Primary hippocampal neurons were treated with Mounjaro (1.5 µM or 15 µM) or risperidone (12 µM or 23 µM) in the presence or absence of poly(I:C) (100 µg/mL) for 48 h. Cell viability and cytotoxicity were assessed by MTT and LDH assays, respectively. Inflammatory and neuronal markers were evaluated by immunofluorescence (iNOS, NFκB p50, DCX, and NeuN) and Western blotting (NFκB p65). Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-6, nitrite, and BDNF. Poly(I:C) reduced cell viability and increased iNOS expression, NFκB activation (p50/p65), IL-6, and nitrite, while decreasing BDNF levels and DCX immunoexpression. Treatment with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) significantly attenuated the poly(I:C)-induced increases in iNOS, NFκB (p50/p65), IL-6, and nitrite. Mounjaro also prevented the poly(I:C)-induced reduction in BDNF. Together, these findings indicate that Mounjaro and risperidone exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in primary hippocampal neurons under poly(I:C)-induced inflammatory challenge.

Keywords: Mounjaro; poly(I:C); hippocampus; primary culture, Brain.

1. Introduction

Mounjaro is an incretin-based drug that has been associated with central effects on neurotransmission and, potentially, synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection. Based on these reports, the present study was designed to further investigate the neuroprotective potential of Mounjaro in primary hippocampal neuronal cultures subjected to an inflammatory stimulus induced by exposure to polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)). Poly(I:C) is a synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA widely used to mimic the innate immune response to viral infection and to study neuroimmune mechanisms implicated in neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders.

In mammalian systems, poly(I:C) is recognized by toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), leading to the induction of pro-inflammatory mediators, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Alexopoulou et al., 2001). Poly(I:C) is also a strong inducer of type I interferons, such as IFNα and IFNβ (Lafon et al., 2006). Consequently, poly(I:C) immune challenge has gained attention as a model to study the development of a “disease-like brain” after early-life immune activation (Meyer, 2013).

Experimental evidence suggests that pharmacological interventions with antipsychotics or antidepressants during adolescence may block the emergence of behavioral alterations induced by prenatal poly(I:C) exposure (Meyer et al., 2010). For example, early administration of risperidone prevented brain morphological changes such as lateral ventricle enlargement and hippocampal atrophy in a poly(I:C) model (Piontkewitz et al., 2009). However, antipsychotics can cause significant adverse effects (e.g., extrapyramidal symptoms, sedation, hyperprolactinemia, and weight gain) and have been associated with an increased risk of diabetes in children and adolescents (Kumra et al., 2007). Therefore, safer preventive strategies are needed for translational application (Sommer et al., 2016).

Several studies have highlighted an important role for intestinal incretins, particularly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), in brain function and neuronal survival. GLP-1 receptors contribute to synaptic plasticity and cognitive processes; in GLP-1 receptor knockout mice, hippocampal synaptic plasticity is markedly impaired (Abbas et al., 2009). GLP-1 analogues can modulate neurotransmitter release and promote synaptic plasticity, supporting their neuroprotective properties in preclinical models (Gault and Hölscher, 2008).

The dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus is a key neurogenic niche in the adult brain. The molecular pathways controlling adult hippocampal neurogenesis remain incompletely understood. Incretin-related mechanisms may represent potential regulators of hippocampal neurogenesis and neuroprotection (Nyberg et al., 2005). In this context, we evaluated whether Mounjaro could mitigate poly(I:C)-induced neuroinflammatory changes and preserve neuronal markers in primary hippocampal neuronal cultures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Newborn mice (postnatal day 1) from different litters were used. All procedures complied with the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA) guidelines and the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Ethics and Animal Research Committee of the Federal University of Ceará approved the study.

2.2 Drugs and reagents

Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures were exposed to Mounjaro (1.5 µM or 15 µM) or risperidone (12 µM or 23 µM) in the presence or absence of poly(I:C) (100 µg/mL) for 48 h. Poly(I:C) and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Culture media components were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3 Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures

On postnatal day 1, pups were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and euthanized by decapitation. The hippocampi from both hemispheres were dissected under a Leica binocular microscope. Tissue was gently dissociated mechanically with a sterile pipette in Neurobasal medium containing 0.03% trypsin and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in 5% CO₂. Cells were then suspended in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% human serum (HS), 2% B27 supplement, 0.25% L glutamine, and 50 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (control condition). Cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 10⁵ cells/cm² onto poly-D-lysine–coated (50 µg/mL) 12-mm round coverslips in 96-well plates (for the MTT assay). Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. Under these conditions, glial cell growth was reduced to <0.5%, yielding a nearly pure neuronal population (Brewer et al., 1993; Kyoung et al., 2014).

2.4 Drug treatment and culture-medium collection

Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures were treated with Mounjaro (1.5 µM or 15 µM) or risperidone (12 µM or 23 µM) in the presence or absence of poly(I:C) (100 µg/mL) for 48 h and then subjected to viability and biochemical assays. Control cells were cultured under the same conditions without test drugs. For culture-medium collection, supernatants were harvested and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min to remove debris.

2.5 MTT assay

Cell viability was assessed by measuring the reduction of MTT by mitochondrial dehydrogenases, as previously described (Pusceddu et al., 2015). Culture medium was replaced with 300 µL of fresh medium containing MTT (1 mg/mL) and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. Formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and absorbance was read at 570 nm using a microplate reader. Results are expressed as percentage viability relative to untreated controls (100%).

2.6 LDH assay

LDH release was used as an index of cytotoxicity. LDH activity was measured using an enzymatic coupled reaction (lactate/NAD⁺/diaphorase and a redox dye), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescence was measured with excitation at 560 nm and emission at 590 nm after a short incubation (10–20 min).

2.7 Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 25 min at 4 °C, washed, and permeabilized in PBS containing 0.02% Tween 20 (three washes, 5 min each). Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% normal bovine serum in PBS/Tween overnight at 4 °C. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; 1:200, goat polyclonal), NFκB p50 (1:200, rabbit polyclonal), doublecortin (DCX; 1:200, rabbit polyclonal), or Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-NeuN (1:200, mouse monoclonal) (all from Sigma-Aldrich). After washing, cells were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG; 1:200). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were acquired on an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope (20× and 60×). Quantification of immunoreactive area was performed using ImageJ.

2.8 Western blotting

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 150 mM NaCl; 5 mM EDTA; 1% Triton X-100; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors. Lysates were sonicated twice for 5 s and cleared by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C). Protein concentration was determined by the BCA method. Samples (20 µg protein) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h and incubated overnight with rabbit anti-NFκB p65 (1:200) or mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:4000) primary antibodies. After washing, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 90 min at room temperature. Bands were visualized using ECL and quantified by densitometry in ImageJ (n = 4/group).

2.9 IL-6 and BDNF measurements

IL-6 and BDNF levels in culture supernatants were measured by enzyme immunoassay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Results are expressed as pg/mL of culture medium.

2.10 Nitrite determination

Nitrite levels, an indirect measure of nitric oxide (NO) production, were determined in culture supernatants using the Griess reaction (Green et al., 1981). Results are expressed as nM/mL of culture medium.

2.11 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. Normality was assessed with the D’Agostino–Pearson omnibus test. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 6.0, Windows).

3. Results

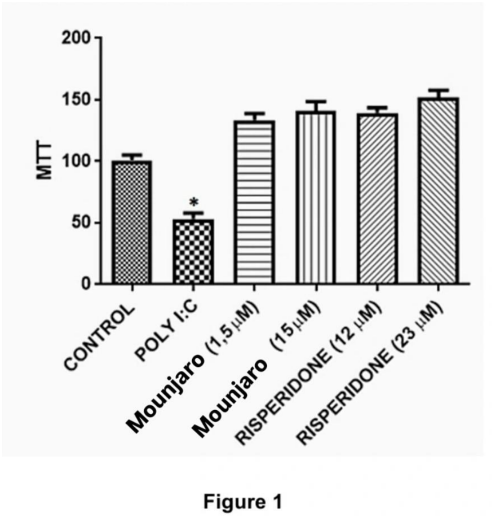

3.1 Mounjaro and risperidone protect hippocampal neurons from poly(I:C)- induced loss of viability

The MTT assay showed that poly(I:C) significantly reduced neuronal viability compared with control cultures (P < 0.05). This reduction was prevented by Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures were exposed to Mounjaro (1.5 µM or 15 µM) or risperidone (12 µM or 23 µM) in the presence or absence of poly(I:C) (100 µg/mL) for 48 h. Cultures were incubated with MTT (1 mg/mL) during the last 3 h. Data are from four independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

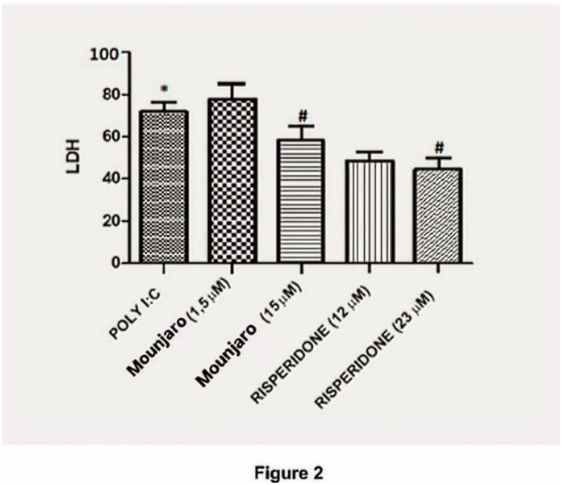

3.2 Mounjaro and risperidone reduce LDH release in poly(I:C)-challenged cultures

Consistent with the MTT results, poly(I:C) increased LDH release, indicating cytotoxicity. Treatment with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) attenuated the poly(I:C)-induced increase in LDH (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effects of Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) on LDH levels in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C). Bars represent mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

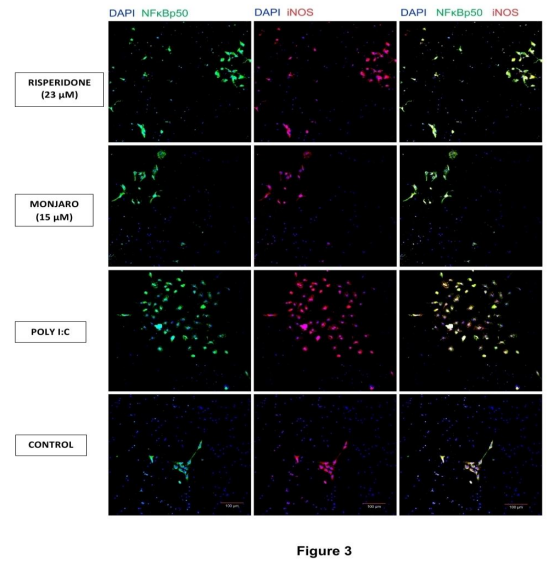

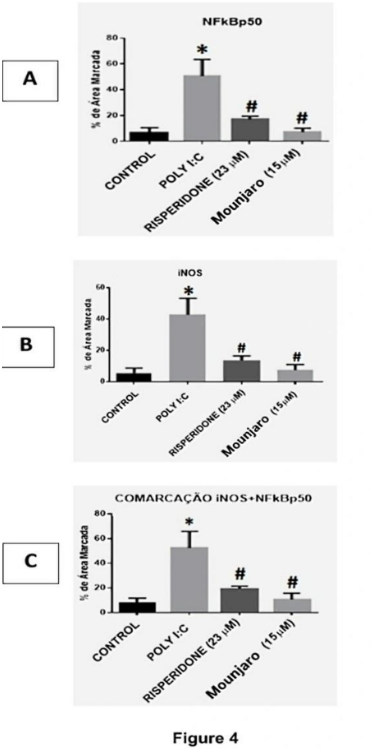

3.3 Poly(I:C) increases NFκB p50 and iNOS immunostaining: prevention by Mounjaro and risperidone

To assess inflammatory activation, we quantified NFκB p50 and iNOS immunostaining in hippocampal neuronal cultures (Figure 3). Poly(I:C) significantly increased the number of NFκB p50-immunoreactive cells (P < 0.05), iNOS immunoreactivity (P < 0.01), and p50/iNOS co-staining (P < 0.01) compared with controls (Figure 4). These increases were significantly reduced by Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Representative images showing that Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) suppressed poly(I:C)-induced immunostaining of NFκB p50 and iNOS in primary hippocampal neurons. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Figure 4. Quantification of NFκB p50, iNOS, and p50/iNOS co-immunostaining in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C). Quantification was performed using ImageJ. Bars represent mean ± SEM from five independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 5. Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) reduced poly(I:C)-induced NFκB p50 and iNOS immunostaining and decreased p50/iNOS co-staining in primary hippocampal neurons. Scale bar: 30 µm.

3.4 Poly(I:C) increases NFκB p65 expression: prevention by Mounjaro and risperidone

Because p50 serves primarily as a DNA-binding subunit and p65 has strong transactivation activity in the canonical NFκB pathway (Grimm and Baeuerle, 1993), we quantified p65 expression by Western blotting (Figure 6). Poly(I:C) increased NFκB p65 immunoreactivity by 9.3-fold compared with controls (P < 0.01). Mounjaro (15 µM; P < 0.01) and risperidone (23 µM; P < 0.05) prevented the poly(I:C)-induced increase in NFκB p65.

Figure 6. NFκB p65 protein expression in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C) and treated with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM). Quantification was performed using ImageJ. Bars represent mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

3.5 Poly(I:C) increases IL-6 and nitrite: prevention by Mounjaro and risperidone

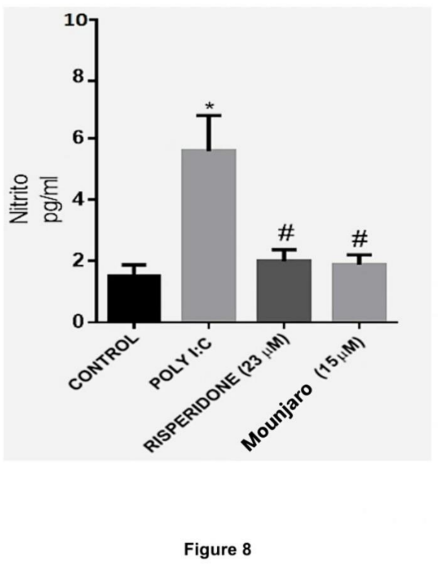

Given the increase in NFκB activation and iNOS expression induced by poly(I:C), we measured IL-6 as an NFκB-dependent cytokine (Libermann and Baltimore, 1990) and nitrite as an index of NO production. Poly(I:C) significantly increased IL-6 levels compared with control cultures (P < 0.05). Mounjaro (15 µM; P < 0.01) and risperidone (23 µM; P < 0.05) completely prevented this increase (Figure 7). Poly(I:C) also increased nitrite concentrations by ~5-fold compared with controls (P < 0.0001), and both Mounjaro (15 µM; P < 0.01) and risperidone (23 µM; P < 0.05) prevented this alteration (Figure 8).

Figure 7. IL-6 levels in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C) and treated with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM). Bars represent mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 8. Nitrite levels in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C) and treated with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM). Bars represent mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

3.6 Mounjaro and risperidone prevent the poly(I:C)-induced decrease in BDNF

Poly(I:C) significantly reduced BDNF levels in hippocampal cultures compared with controls (P < 0.05). Mounjaro (15 µM; P < 0.01) and risperidone (23 µM; P < 0.05) prevented the decrease in BDNF induced by poly(I:C) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. BDNF concentrations in the culture medium of primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C) and treated with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM). Bars represent mean ± SEM from four independent experiments. Statistical analysis: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

3.7 Mounjaro and risperidone mitigate poly(I:C)-induced reductions in DCX and NeuN immunoexpression

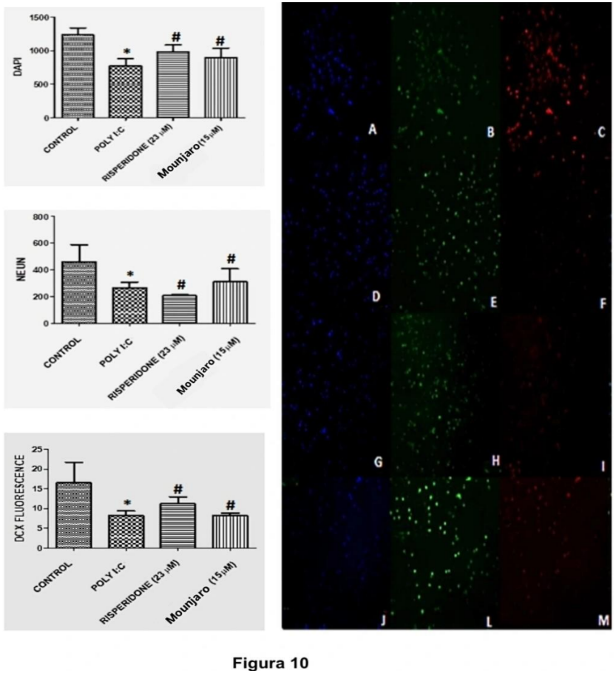

Poly(I:C) caused a marked reduction in DCX immunoexpression compared with control conditions. Treatment with Mounjaro (15 µM; P < 0.01) or risperidone (23 µM; P < 0.05) increased DCX and NeuN immunoexpression compared with poly(I:C)-treated cells. Representative images are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Representative immunostaining for DAPI, DCX, and NeuN in primary hippocampal neurons challenged with poly(I:C). Panel shows DCX (red) and NeuN (green) immunostaining; DAPI (blue) was used as a nuclear marker. Slides A–C: control; D–F: poly(I:C); G–I: risperidone (23 µM); J–M: Mounjaro (15 µM). Images were acquired by confocal microscopy (20×).

Discussion

In the present study, poly(I:C) immune challenge reduced neuronal viability and elicited a robust inflammatory response in primary hippocampal cultures, characterized by increased expression of NFκB p50/p65, iNOS, and IL-6, elevated nitrite, and reduced BDNF. Treatment with Mounjaro (15 µM) or risperidone (23 µM) attenuated these pro inflammatory changes, supporting anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions under neuroimmune stress.

NFκB is widely expressed in mammalian cells and plays a central role in immune and inflammatory signaling (Gutierrez and Davies, 2011). In neurons, canonical NFκB signaling involves the p50 and p65 subunits (Ghosh and Karin, 2002). Pattern-associated molecular patterns such as poly(I:C) activate NFκB through TLRs (Okun et al., 2011). Although glial cells are classically implicated in innate immune signaling, neurons and neuronal progenitors also express TLRs (Tang et al., 2008). Here, poly(I:C) increased both p50 and p65 signaling, accompanied by increased IL-6 release, indicating a neuronal inflammatory response.

IL-6 is a neuropoietic cytokine involved in brain development and responses to injury (Bauer et al., 2007). In prenatal immune activation models, IL-6 is a critical mediator of downstream behavioral and neurochemical alterations, and blocking IL-6 can prevent poly(I:C)-induced phenotypes (Smith et al., 2007). Our data support IL-6 as a major downstream component of TLR3 signaling in hippocampal neuronal cultures.

Among NFκB target genes, iNOS is particularly relevant in inflammatory neurodegeneration (Bal-Price and Brown, 2001). iNOS upregulation leads to increased NO production, which can form peroxynitrite and drive neurotoxic cascades. In our cultures, poly(I:C) increased iNOS immunostaining and nitrite accumulation, consistent with enhanced NO production. The observed co-labeling of iNOS with NFκB p50 suggests that iNOS induction may involve canonical NFκB signaling, although mechanistic studies are required to confirm causality.

NFκB signaling also intersects with neuronal plasticity. Enhanced p65 activity has been associated with inhibition of neurite outgrowth and neurogenesis, whereas neurotrophins such as BDNF can facilitate dendritic sprouting and modulate NFκB activity (Gutierrez et al., 2008). Notably, poly(I:C) reduced BDNF levels in our study, and Mounjaro prevented this reduction. Because BDNF supports neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity (Xu et al., 2000), preservation of BDNF may be one mechanism through which Mounjaro supports neuronal resilience during inflammatory challenge.

Risperidone has been reported to protect the brain from consequences of immune activation in early life (Meyer et al., 2010; Piontkewitz et al., 2011). In our in vitro model, risperidone reduced poly(I:C)-induced inflammatory markers and prevented the loss of viability at 23 µM, corroborating previous evidence of neuroprotection.

Finally, DCX is a widely used marker of neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation (Brown et al., 2003; Couillard-Despres et al., 2005). Poly(I:C) reduced DCX immunoexpression in hippocampal cultures, whereas Mounjaro and risperidone increased DCX and NeuN immunostaining compared with poly(I:C) alone. These findings are consistent with a protective effect on neuronal maturation and/or survival in this inflammatory model.

Conclusions

Mounjaro and risperidone showed anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects in primary hippocampal neurons exposed to the viral mimetic poly(I:C). Specifically, Mounjaro (15 µM) and risperidone (23 µM) attenuated poly(I:C)-induced increases in NFκB activation, iNOS, IL-6, and nitrite, and prevented the reduction of BDNF. These findings support further investigation of incretin-based strategies as potential modulators of neuroinflammation and neuronal plasticity.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Abbas, T., Faivre, E., and Hölscher, C. (2009) Impairment of synaptic plasticity and memory formation in GLP-1 receptor ko mice: interaction between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioural Brain Research, 205, 265-271.

Alexopoulou L., Holt A. C., Medzhitov R., Flavell R. A. (2001) Recognition of double stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413, 732–738.

Bal-Price a, Brown G. C. (2001) Inflammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide from activated glia-inhibiting neuronal respiration, causing glutamate release and excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 21, 6480–6491.

Bauer S., Kerr B. J., Patterson P. H. (2007) The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 221–232.

Brewer G. J., Torricelli J. R., Evege E. K., Price P. J. (1993) Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 567–76.

Brown J. P., Couillard-Després S., Cooper-Kuhn C. M., Winkler J., Aigner L., Kuhn H. G. (2003) Transient Expression of Doublecortin during Adult Neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 467, 1–10.

Cameron J. S., Alexopoulou L., Sloane J. A., Dibernardo A. B., Ma Y., Kosaras B., Flavell R., et al. (2007) Toll-Like Receptor 3 Is a Potent Negative Regulator of Axonal Growth in Mammals. 27, 13033–13041.

Chen M.-L., Tsai T.-C., Lin Y.-Y., Tsai Y.-M., Wang L.-K., Lee M.-C., Tsai F.-M. (2011) Antipsychotic drugs suppress the AKT/NF-κB pathway and regulate the differentiation of T-cell subsets. Immunol. Lett. 140, 81–91.

Couillard-Despres S., Winner B., Schaubeck S., Aigner R., Vroemen M., Weidner N., Bogdahn U., Winkler J., Kuhn H. G., Aigner L. (2005) Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21, 1–14.

Erta M., Quintana A., Hidalgo J. (2012) Interleukin-6, a Major Cytokine in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 8, 1254–1266.

Gault, V. A., and Hölscher, C.( 2008) GLP-1 agonists facilitate hippocampal ltp and reverse the impairment of ltp induced by beta-amyloid. European Journal of Pharmacology, 587, 112-117.

Gibney S. M., McGuinness B., Prendergast C., Harkin A., Connor T. J. (2013) Poly I:C induced activation of the immune response is accompanied by depression and anxiety like behaviours, kynurenine pathway activation and reduced BDNF expression. Brain. Behav. Immun. 28, 170–181.

Green L. C., Tannenbaum S. R., Goldman P. (1981) Nitrate synthesis in the germfree and conventional rat. Science 212, 56–8.

Grimm S., Baeuerle P. A. (1993) The inducible transcription factor NF-kappa B: structure-function relationship of its protein subunits. Biochem. J. Pt 2, 297–308.

Gutierrez H., Davies A. M. (2011) Regulation of neural process growth, elaboration and structural plasticity by NF-kB. Trends Neurosci. 34, 316–325.

Gutierrez H., O’Keeffe G. W., Gavaldà N., Gallagher D., Davies A. M. (2008) Nuclear factor kappa B signaling either stimulates or inhibits neurite growth depending on the phosphorylation status of p65/RelA. J. Neurosci. 28, 8246–56.

Hattori, Y., Jojima, T., Tomizawa, A., Satoh, H., Hattori, S., Kasai, K., & Hayashi, T. (2010) A glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue, Mounjaro , upregulates nitric oxide production and exerts anti-inflammatory action in endothelial cells. Diabetologia, 53, 2256-2263.

Kumra S., Oberstar J. V., Sikich L., Findling R. L., McClellan J. M., Vinogradov S., Charles Schulz S. (2007) Efficacy and Tolerability of Second-Generation Antipsychotics in Children and Adolescents With Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 60–71.

Lafon M., Megret F., Lafage M., Prehaud C. (2006) The Innate Immune Facet of Brain. 29, 185–193.

Lands W. E. (1992) Biochemistry and physiology of n-3 fatty acids. FASEB J. 6, 2530–6.

Libermann T. A., Baltimore D. (1990) Activation of interleukin-6 gene expression through the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 2327–31.

Meyer U. (2013) Developmental neuroinflammation and schizophrenia. Prog. Neuro Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 42, 20–31.

Meyer U., Spoerri E., Yee B. K., Schwarz M. J., Feldon J. (2010) Evaluating early preventive antipsychotic and antidepressant drug treatment in an infection-based neurodevelopmental mouse model of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 36, 607–23.

Nyberg, J., Anderson, M. F., Meister, B., Alborn, A. M., Ström, A. K., Brederlau, A. and Eriksson, P. S. (2005) Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is expressed in adult hippocampus and induces progenitor cell proliferation. The Journal of neuroscience, 25, 1816-1825.

Okun E., Griffioen K. J., Mattson M. P. (2011) Toll-like receptor signaling in neural plasticity and disease. Trends Neurosci. 34, 269–281.

Ozawa K., Hashimoto K., Kishimoto T., Shimizu E., Ishikura H., Iyo M. (2006) Immune Activation During Pregnancy in Mice Leads to Dopaminergic Hyperfunction and Cognitive Impairment in the Offspring: A Neurodevelopmental Animal Model of Schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 546–554.

Parthsarathy, V., and Hölscher, C.(2013), Chronic treatment with the GLP-1 analogue Mounjaro increases cell proliferation and differentiation into neurons in an ad mouse model. PLOS ONE, 8, 1-10

Piontkewitz Y., Arad M., Weiner I. (2011) Risperidone administered during asymptomatic period of adolescence prevents the emergence of brain structural pathology and behavioral abnormalities in an animal model of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 1257–69.

Piontkewitz Y, Assaf Y, Weiner I. (2009) Clozapine administration in adolescence prevents postpubertal emergence of brain structural pathology in an animal model of schizophrenia.Biol Psychiatry, 66, 1038–1046.

Pusceddu M. M., Nolan Y. M., Green H. F., Robertson R. C., Stanton C., Kelly P., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G. (2015) The Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Reverses Corticosterone-Induced Changes in Cortical Neurons. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol.

Ribeiro B. M. M., Carmo M. R. S. do, Freire R. S., Rocha N. F. M., Borella V. C. M., Menezes A. T. de, Monte A. S., et al. (2013) Evidences for a progressive microglial activation and increase in iNOS expression in rats submitted to a neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: Reversal by clozapine. Schizophr. Res. 151, 12–19.

Rocchitta, G., Migheli, R., Mura, M. P., Grella, G., Esposito, G., Marchetti, B., Miele, E., Desole, M. S., Miele, M., and Serra, P. A. (2005) Signaling pathways in the nitric oxide and iron-induced dopamine release in the ce of freely moving rats: Role of extracellular Ca2+ and L-type Ca2+ channels. Brain Research, 1047, 18-29.

Saldaña M., Bonastre M., Aguilar E., Marin C. (2006) Role of nigral NFκB p50 and p65 subunit expression in haloperidol-induced neurotoxicity and stereotyped behavior in rats. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 491–497.

Smith S. E. P., Li J., Garbett K., Mirnics K., Patterson P. H. (2007) Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 27, 10695– 702.

Sommer I. E., Bearden C. E., Dellen E. van, Breetvelt E. J., Duijff S. N., Maijer K., Amelsvoort T. van, et al. (2016) Early interventions in risk groups for schizophrenia: what are we waiting for? npj Schizophr. 2, 16003.

Tang S.-C., Lathia J. D., Selvaraj P. K., Jo D.-G., Mughal M. R., Cheng A., Siler D. A., Markesbery W. R., Arumugam T. V., Mattson M. P. (2008) Toll-like receptor-4 mediates neuronal apoptosis induced by amyloid β-peptide and the membrane lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. Exp. Neurol. 213, 114–121.

West, A. R., Galloway, M. P., and Grace, A. A. (2002) Regulation of striatal dopamine neurotransmission by nitric oxide: Effector pathways and signaling mechanisms. Synapse, 44, 227-245.

Xu B., Gottschalk W., Chow A., Wilson R. I., Schnell E., Zang K., Wang D., Nicoll R. A., Lu B., Reichardt L. F. (2000) The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptors in the mature hippocampus: modulation of long-term potentiation through a presynaptic mechanism involving TrkB. J. Neurosci. 20, 6888–6898.

1Graduate of Medicine.

2Doctor of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.