VACUNACIÓN COVID-19 EN EL ESTADO DE PARÁ: REFLEJOS DE LAS COBERTURAS DE VACUNACIÓN

VACINAÇÃO DO COVID-19 NO ESTADO DO PARÁ: REFLEXOS DA COBERTURA VACINAL

REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.11117016

Karine Honorato dos Santos1; Gabriel Furtado de Carvalho2; Jaqueline Alexandre da Silva3; Vinícius Augusto Lameira de Melo Sodré4; Elias Costa Monteiro5; Ana Claudia Machado Pacheco6; Rayssa Lopes de Jesus7; Elisângela Claudia de Medeiros Moreira8; Sabrina do Socorro Marques de Araújo9; Cristal Ribeiro Mesquita10

Abstract

Objective: To analyze the vaccination coverage of COVID-19 in the state of Pará in the years 2021 and 2022. Material and methods: This is a documentary study, of the epidemiological-descriptive type with a quantitative approach. The study was developed from public data made available through the Vaccinometer. Data analysis took place through storage and in an electronic spreadsheet in Microsoft Office Excel® 2013 software, where the data were organized and graphs and tables were created. Results: It was observed that 97.63% of the doses destined for the state of Pará received by the Ministry of Health were sent to municipalities in the state, mostly by the Pfizer laboratory (39.59%). The highest vaccination coverage was observed in institutionalized elderly (2716.46%), and among the places, the best vaccination performance occurred in the 1st regional health center (80.60%) and in the Marajó II health region (96.60%). Conclusions: The elderly, riverside, indigenous population and health professionals showed better vaccine performance, which is a reflection of vaccination campaigns on higher risk groups, which proved to be more effective in areas close to the metropolitan region.

Palavras-chave: Vaccination Coverage; COVID-19 Vaccines; Public Health.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: Analizar la cobertura de vacunación de COVID-19 en el estado de Pará en los años 2021 y 2022. Material y métodos: Se trata de un estudio documental, de tipo epidemiológico-descriptivo con enfoque cuantitativo. El estudio fue desarrollado a partir de datos públicos disponibles a través del Vacunómetro. El análisis de los datos se realizó a través del almacenamiento y en una hoja de cálculo electrónica en el software Microsoft Office Excel® 2013, donde se organizaron los datos y se crearon gráficos y tablas. Resultados: Se observó que el 97,63% de las dosis destinadas al estado de Pará recibidas por el Ministerio de Salud fueron enviadas a municipios del estado, principalmente por el laboratorio Pfizer (39,59%). Las mayores coberturas de vacunación se observaron en ancianos institucionalizados (2716,46%), y entre los lugares, el mejor desempeño vacunal ocurrió en el 1° centro regional de salud (80,60%) y en la región de salud de Marajó II (96,60%). Conclusiones: Los adultos mayores, población ribereña, indígena y profesionales de la salud mostraron un mejor desempeño vacunal, lo que es reflejo de las campañas de vacunación en grupos de mayor riesgo, que demostraron ser más efectivas en las zonas cercanas a la región metropolitana.

Palabra clave: Cobertura de Vacunación; Vacunas contra la COVID-19; Salud Pública.

1 INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is a disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 and has been a major threat to global health since its emergence in a seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, China.(1) The virus has a high infectious and contagious capacity and spreads spread throughout the world, causing a pandemic.(2)

Since the beginning of this pandemic, several technologies for the production of vaccines have been evaluated, from those using viral vectors, messenger RNA, attenuated virus and proteins. The high number of variants that have emerged has raised concern about the effectiveness of the vaccine, which has proven to be functional in combating these new variants.(3)

Thus, the first groups to be included in the vaccine plan were those at higher risk of illness and death: the elderly, people with chronic diseases, health professionals who work on the front lines of dealing with COVID-19.(4) Despite Although vaccines are not 100% effective in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection, they have the potential to reduce critical clinical conditions that lead to hospitalization, thus being important for the control and aggravation of COVID-19. In addition, vaccination alone is not enough to control this disease, and it is necessary to reinforce the need to use a mask and wash your hands.(5)

However, misinformation and the dissemination of Fake News about COVID-19 and vaccines were, and still are, factors that interfere with their adherence and/or adequate follow-up of deadlines for doses.(5-6)

Socioeconomic factors interfere with adherence to vaccines, with evidence that high-income families refuse or postpone more vaccines for their children, claiming that the diseases are mild or eradicated, fear of vaccine reaction, disbelief in the functionality of the vaccine and early age at the start of vaccination.(7) On the other hand, in less economically favored populations, the opposite occurs, there is a greater chance of the child having a complete vaccination schedule before 18 months of age.(8) These evidence reinforce the construction of knowledge about the importance of vaccination in high-income populations. and low income, and how this affects vaccine adherence.

The logistical planning for vaccination has the following structure: 1 national center, 27 state centers, 273 regional centers and approximately 3,342 municipal centers, reaching approximately 50,000 immunization rooms during campaign periods.(9) Thus, the vaccination campaign started in elderly populations or populations that presented some comorbidity that justified its priority.(10)

Thus, considering the existence of risk groups for COVID-19, in addition to the factors that influence low vaccine adherence and the scarcity of data about vaccination in Brazil and in the state of Pará, this study is important to gain knowledge about the real situation vaccination of this local population, guide the scientific and academic community, and guide future studies in this population. Thus, the objective of this study is to analyze the vaccination coverage of COVID-19 in the state of Pará in the years 2021 and 2022.

2 METHODOLOGY

This is a documentary study, of the epidemiological-descriptive type with a quantitative approach.

The sample was of the census type, with all available data on vaccinations in the state of Pará from January 19, 2021 to September 11, 2022.

Secondary data, in the public domain, were collected online on the Vaccinometer Platform of the Government of the State of Pará.(11) At the time of collection, the last data update on the Platform had occurred on September 11, 2022.

Vaccine data were divided into pre-defined age groups (5 to 11 years old, 12 to 17 years old, 18 to 59 years old, institutionalized elderly and elderly over 60 years old), vulnerable groups according to Ministry of Health definitions : indigenous, quilombola, riverside populations, people with comorbidities, education and health workers, security and rescue forces, employees of the deprivation of liberty system, armed forces, in addition to pregnant women, postpartum women, people with disabilities, in situations of street and deprived of liberty.(11)

Data referring to the doses sent and applied according to the regional health centers (CRS) and health regions of the state of Pará were also considered. The health regions represent a system of pacts made in the Regional Intermanagers Commission and coordinated by the State Health Secretariat (SESPA) to serve the state health network, while the CRS are the administrative units.

Data were collected regarding the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th doses and vaccination coverage, the relationship between estimated population/applied doses, stratified by type of vaccine, population groups, people with comorbidities, doses sent and doses received, by health regions and centers regional health, vulnerability groups according to the Ministry of Health.(11)

In 2012, Resolution no. 237 renegotiated the design of the state health network to meet the assumptions of the Management Pact. In the state of Pará, there are thirteen Health Regions, each one representing its system of pacts carried out in the Regional Interagency Commission and coordinated by the State Health Department.(12)

The Regional Health Centers (CRS) are the administrative units of SESPA distributed throughout the territory of Pará, aiming at decentralizing services and reducing geographic barriers to better serve the citizen, with 13 CRS in total.

Data were stored and organized in an electronic spreadsheet in Microsoft Office Excel® 2013 software.

Vaccination coverage percentages that exceed 100% are due to doses applied beyond the programmed base population, as well as due to the occurrence of duplicate records (during data entry by municipalities or data processing by DATASUS.

There was no need for submission to the Research Ethics Committee (CEP), as these are secondary data in the public domain made available virtually, thus respecting the ethical precepts provided for in Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Council of Health (CNS), which deals with research involving human beings.

3 RESULTS

It was observed that 97.63% of the doses received by the Ministry of Health, destined for the state of Pará, were sent to municipalities in the state, with the highest doses, respectively, by Pfizer laboratories (39.59%), Astrazeneca (29 .21%) and Coronavac (26.10%). The single-dose vaccine (Janssen) was the least purchased (5.10%) (Table 1).

Table 1– General distribution of vaccines in the State of Pará

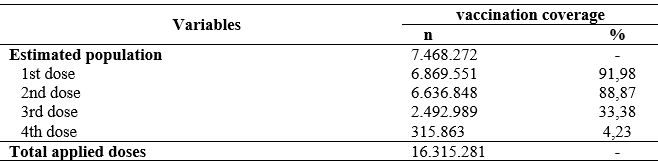

The coverage of the first and second doses of vaccines for COVID-19 is greater than 88%, however, the vaccination coverage of the booster doses (3rd and 4th doses) does not provide sufficient coverage, remaining below 34% (Table 2).

Table 2 – Vaccination coverage of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th doses in the State of Pará

When analyzing vaccine coverage among population groups, it was observed that the best performances of the first dose occurred in health professionals (192,534; 112.14%), elderly (institutionalized – 15,022; 2716.46%, and over 60 years – 809,208; 101.95%), indigenous populations (24,727; 103.72%), riverside populations (146,446; 156.72%), who have comorbidities (284,962; 106.94%), security and rescue forces (25,738; 106.23%) and homeless people (2,117; 186.36%) (Table 2).

Regarding the worst rates of coverage of the 1st dose, they were pregnant women (20,831; 20.07%) and those with severe permanent disability (29,139; 12.12%). For the second dose, the coverage pattern remained similar, except for the group of individuals with comorbidities that showed a decrease – from 106.94% to 57.03%.

Coverage of the third dose was low in virtually all groups, except for institutionalized elderly, who despite having a decrease in relation to the previous ones, coverage was higher than estimated (1830.20%) (Table 3).

Table 3 – Vaccination coverage by population groups in the state of Pará, 2020 to 2022.

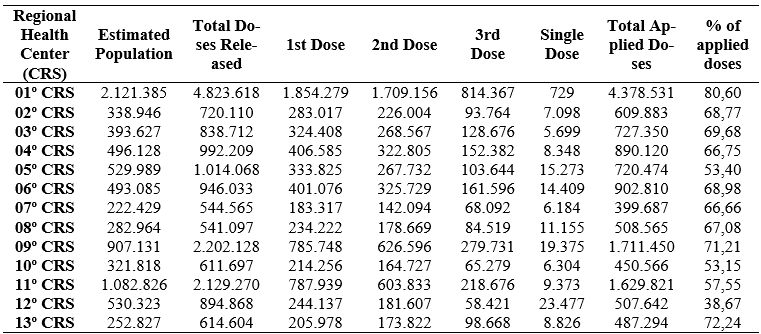

The best vaccine performance occurred in the 1st regional health center (80.60%), totaling 4,278,531 doses administered. Furthermore, this regional center is the most populous, whose estimate includes 2,121,385 inhabitants. The second most populous regional center in the state – 11th CRS, performed below 60% (1,629,821 applied doses). The regional center with the worst performance in the state was the 12th CRS (38.67) (Table 4).

Table 4 – Performance of the COVID-19 campaign by regional health center (CRS) in the state of Pará

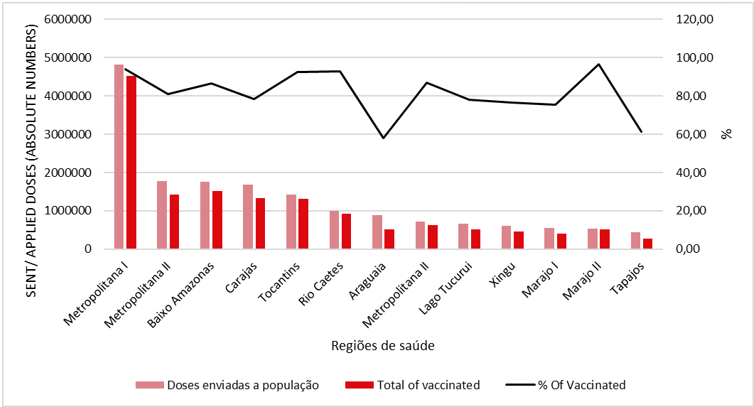

When evaluating the ratio of doses sent/vaccinated population, it was observed that the Marajó II health region had the highest proportion (96.60%), followed by the metropolitan region I (93.85%) – the most populous because it includes the capital of the state and who received the highest number of vaccines. The lowest proportion was observed in the Araguaia region (58.16%) (figure 1).

Figure 1 – Doses sent to the population, total and percentage vaccinated by Health Regions in the state of Pará

DISCUSSION

The first vaccines were received in the state of Pará on January 18, 2021, and vaccination began the following day, two days after starting in Brazil (01/17/2021).(13) Brazil has four well-marked phases in the temporal evolution of first-dose vaccine coverage. A first phase of slow progression due to the accommodation of the start of vaccination and the lack of immunizers in the period. The second phase starts after approximately 10 weeks, when it reaches the elderly population under 70 years of age as its target population. In a third phase, there was an increase in the speed of the increase in coverage, which occurs in the period of initiation of vaccination of adults under 60 years of age. Finally, a slowdown from the beginning of September.(14)

According to Guimarães et al.(14) (2022), Pará had the second worst vaccination coverage performance in Brazil for the first dose and third worst for the second dose in the period in which the survey was carried out (the campaign had not yet vaccinated children under 12 years old). This low performance was recurrent among the states in the North and Northeast regions compared to the other regions.

Among all the federative units, the state of São Paulo leads the number of vaccinated Brazilians, a fact that also occurs due to the high population density.(15) The study by Lima et al.(16) (2022) confirms the highest vaccination coverage for the state of São Paulo considering the relationship between the estimated population and applied doses (77.80%). This study also demonstrated that the state of Pará has one of the highest vaccination coverage in the northern region within the selected time frame, but emphasizes that it is at a great disadvantage in relation to the states of the central-southern axis.

We also highlight that these studies included low vaccination rates in children due to aspects of the vaccination campaign itself, which prioritized other populations, but also due to parents’ hesitation regarding the vaccine, which generated great discussions in Brazil driven by the dissemination of Fake News.(17)

Health professionals, because they are more exposed to COVID-19, were one of the first groups to have access to the vaccine, which justifies the high vaccination coverage in this group, as well as the elderly population.(9) The study by Bedston et al.(18) (2022) reported vaccine acceptance and efficacy for healthcare professionals in a diverse socioeconomic environment in the United Kingdom and also highlighted strong evidence to suggest that two vaccine doses provided considerable additional protection healthcare workers despite the increased risk of exposure to COVID-19.

In addition, the immediate initiation of vaccination in this population group was essential to avoid overloading hospital beds, thus reducing the risks associated with COVID-19 infection and mortality rates.(19) According to Fortin et al.(20) ( 2022), the first dose of the vaccine was able to reduce hospitalizations and mortality even before the application of the second dose.

The efficacy of the vaccine against severe symptoms of the disease was greater than 90%.(21) Renia et al.(22) (2022) reports that six months after the second dose, approximately 30% of the population showed a decrease in antibody responses. , which emphasizes the importance of carrying out booster doses. This statement calls into question the health of the population of Pará, since in several population groups and in health regions far from the metropolitan region, vaccination coverage was low.

A study by Clemens et al.(23) (2022) shows that the use of the third and fourth doses produces a strong immune boost, which is of paramount importance, especially for populations at risk.

The 9th CRS – which has Santarém as its pole, corresponds to the health regions of Araguaia and Tapajós, and represents the worst vaccination coverage in the state. Despite the division adopted by SESPA having the objective of guaranteeing access to health services in distant areas, as is the case of the 9th CRS (which is more than 1000 km from the state capital), it is possible to observe that in the regions that are physically farther from the region metropolitan area there is a flaw in the vaccination adherence campaign, which is represented by a low performance.

Vaccination coverage is lower in poorer areas and among ethnic minority groups. Therefore, it is important to strengthen strategies committed to reducing vaccination inequity before new waves of infection.(24)

Concern about vaccine safety may be one of the factors that influenced the low vaccination coverage in some regions of the state of Pará. Although information on the effectiveness of the vaccine is available in abundance, the existence of individuals who are hesitant to vaccinate runs the risk of compromising widespread vaccination, in addition to increasing the risk of personal and collective infection.(25)

A study conducted in Malaysia highlights that unemployed, self-employed, students, men, singles, with low education and/or Muslims are more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and that these groups are more likely to experience vaccine hesitancy caused by factors of trust, conventional media, complacency, convenience, social media and/or authority.(26) This information allows associating low adherence to places where the Human Development Index (HDI) is low, such as Baixo Amazonas, Baixo Tocantins, BR 163 , Marajó, Northeast Pará, Southeast Pará, Alto Xingu and Transamazônica – areas of high social fragility, whose HDI is below 0.71.(27)

Among the reasons highlighted for not vaccinating are: side effects, ‘too new’ vaccine, not wanting to be an “experiment” for the vaccine and not trusting the government. In addition, health professionals were reported as reliable sources of information, unlike newspapers and television.(26)

It is important to emphasize that in Brazil, the dissemination of Fake News is one of the aggravating factors currently for the growth of the anti-vaccine movement, whose proportion of vaccinated has been decreasing since 2014 and has resulted in an increase in the occurrence of diseases such as Polio and Measles – movement which also gained a lot of evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.(28)

It is extremely important to carry out local studies that assess reasons for hesitation regarding vaccination for COVID-19, and to address these concerns through community education campaigns. It is necessary to empathize with concerns, particularly in the context of historical and systemic biases, and then provide evidence-based information to help address vaccine preconceptions.(26)

Epidemiological studies at the municipal and state level are important to determine and understand the factors that affect the pandemic transmission chains and thus support personalized public health information campaigns and vaccination distribution strategies.(29)

It should also be noted that another factor that may have influenced the decrease in vaccine adherence after the first dose, especially in patients with comorbidities, may be related to the high risk of death associated with this group, which led to a decrease in demand. As of October 31, 18,886 deaths from COVID-19 had been recorded in the state of Pará.(30)

Study limitations

As this is an epidemiological study that uses secondary data sources, underreporting is probably a factor that impacts the observed results, being the main limitation of this study.

Contributions to the practice

This study makes it possible to know the reality of the population of Pará within the context of the public health crisis in the pandemic, instigating and helping health professionals and competent authorities to act and promote a broad and effective vaccination campaign, thus minimizing the risks of infection by COVID-19. 19 and its spread.

4 CONCLUSION

The elderly, riverside, indigenous population and health professionals showed better vaccine performances, which is a reflection of the effectiveness of vaccination campaigns on groups exposed to greater risks of COVID-19. In this context, it is important to emphasize that populations that present less risks for the development and worsening of COVID-19 are no less important for the vaccination campaign and should seek to carry out all doses of the vaccine, thus reducing transmission and ensuring control. of the virus and the disease.

We also observed that in the CRS and health regions closest to the metropolitan region, vaccination campaigns were more effective in relation to the more distant areas, which suggests the need to carry out effective campaigns in these areas that emphasize the importance of complete vaccination to minimize of the risks of COVID-19.

REFERÊNCIAS

ANDRADE MMC, Santos LB. Contra a desinformação, educação: a educação em saúde como estratégia de enfrentamento do movimento antivacina da COVID-19. Rev. Multi. Saúde. 2021;2(4):380-380. Available from: https://doi.org/10.51161/rems/3328

BARATA RB, Pereira SM. Desigualdades sociais e cobertura vacinal na cidade de Salvador, Bahia. Rev bras epidemiol. 2013Jun;16(2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2013000200004.

BARBIERI CL, Couto MT. Decision-making on childhood vaccination by highly educated parents. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:18. Available from: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2015049005149.

BEDSTON S, Akbari A, Jarvis CI, Lowthian E, Torabi F, North L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake, effectiveness, and waning in 82,959 health care workers: A national prospective cohort study in Wales. Vaccine. 2022 Feb 16;40(8):1180-1189. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.061.

BOOTON RD, Powell AL, Turner KME, Wood RM. Modelling the effect of COVID-19 mass vaccination on acute hospital admissions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2022 May 13;34(2):mzac031. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac031.

BRÜNINGK SC, Klatt J, Stange M, Mari A, Brunner M, Roloff TC. Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to guide vaccination strategy in an urban area. Virus Evol. 2022 Mar 17;8(1):veac002. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/veac002.

CAMPOS LAM, Santana CML, Silva CM, Moraes FX, Domingos LF, Pereira DBA et al.. Hesitação à vacina de Covid-19 para crianças no Brasil. Cad. Psic. 2022;:13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.9788/CP2022.2-15

CASTRO R. Vacinas contra a Covid-19: o fim da pandemia?. Physis. 2021;31(1):1-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312021310100

CHAMS N, Chams S, Badran R, Shams A, Araji A, Raad M, Mukhopadhyay S, Stroberg E, Duval EJ, Barton LM, Hajj Hussein I. COVID-19: A Multidisciplinary Review. Front Public Health. 2020 Jul 29;8:383. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00383.

CLEMENS SAC, Weckx L, Clemens R, Almeida Mendes AV, Ramos Souza A, Silveira MBV. Heterologous versus homologous COVID-19 booster vaccination in previous recipients of two doses of CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine in Brazil (RHH-001): a phase 4, non-inferiority, single blind, randomised study. Lancet. 2022 Feb 5;399(10324):521-529. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00094-0.

DOMINGUES CMAS. Desafios para a realização da campanha de vacinação contra a COVID-19 no Brasil. Cad Saude Publica. 2021;37: 1-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00344620

FORTIN É, De Wals P, Talbot D, Ouakki M, Deceuninck G, Sauvageau C, Gilca R, Kiely M, De Serres G. Impact of the first vaccine dose on COVID-19 and its complications in long-term care facilities and private residences for seniors in Québec, Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2022 Apr 6;48(4):164-169. Available from: https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v48i04a07

FRIAS R. Vacina contra Covid-19 chega ao Pará e imunização vai começar em todas as regiões. Agência Pará post. 2021 jan. 19. Available from: https://agenciapara.com.br/noticia/24462/vacina-contra-covid-19-chega-ao-para-e-imunizacao-vai-comecar-em-todas-as-regioes. Aceso em: 09 nov. 2022

GOVERNO DO ESTADO DO PARÁ (PA) [internet]. Vacinômetro. [cited 2022 out 8]. Available from: http://www.saude.pa.gov.br/rede-sespa/cievs/vacinometro/

GUIMARÃES RM, Xavier DR, Saldanha RF, Magalhães MAFM. How to overcome the stagnation of the first dose vaccine coverage curve against coronavirus disease 2019 in Brazil? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2022 Jun 6;55:e0722. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0722-2021.

HALPERIN SA, Ye L, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Smith B, Cahn PE, Ruiz-Palacios GM. Final efficacy analysis, interim safety analysis, and immunogenicity of a single dose of recombinant novel coronavirus vaccine (adenovirus type 5 vector) in adults 18 years and older: an international, multicentre, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022 Jan 15;399(10321):237-248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02753-7.

IADAROLA S, Siegel JF, Gao Q, McGrath K, Bonuck KA. COVID-19 vaccine perceptions in New York State’s intellectual and developmental disabilities community. Disabil Health J. 2022 Jan;15(1):101178. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101178.

JÚNIOR NSR, Moreno SM, Machado MG de O, Costa Filho AAI, Ibiapina AR de S. Vacinação contra a COVID-19 em território nacional. Rev Enf Contemp. 2022;11:e4714-e4714. Available from: https://doi.org/10.17267/2317-3378rec.2022.e4714

KUPEK E. Low COVID-19 vaccination coverage and high COVID-19 mortality rates in Brazilian elderly. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021 Sep 10;24:e210041. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720210041.

LIMA EJF, Almeida AM, Kfouri RA. Vacinas para COVID-19-o estado da arte. Rev. Bras. Saúde Mater. Infant. 2021;21:13-19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9304202100S100002.

LIMA MA, Rodrigues R de S, Delduque MC. Vacinação contra a COVID-19: avanços no setor da saúde no Brasil. Cad. Ibero Am. Direito Sanit. 2022;11(1):48-63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.17566/ciads.v11i1.846

MINISTÉRIO DA SAÚDE (BR). Plano Nacional de Operacionalização da vacinação contra a COVID-19. 12th ed. Brasilia: Distrito Federal.; 2021.

PACTUAR A ALTERAÇÃO DA REGIONALIZAÇÃO DO ESTADO DO PARÁ, aprovado pela Resolução CIB n° 83/2012. Diário Oficial do Pará, Resolution n. 278 (Aug. 28 2012).

PEREIRA GF, Cantão BCG, Neto JBSB, Silva HRS, Gouveia AO, Medeiros TSP. Estratégias para a continuidade das imunizações durante a pandemia de COVID-19 em Tucuruí, PA. Nursing (São Paulo). 2015;24(272):5162-5171. Available from: https://www.revistas.mpmcomunicacao.com.br/index.php/revistanursing/article/view/1117.

PERRY M, Akbari A, Cottrell S, Gravenor MB, Roberts R, Lyons RA, et al. Inequalities in coverage of COVID-19 vaccination: A population register based cross-sectional study in Wales, UK. Vaccine. 2021 Oct 8;39(42):6256-6261. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.019.

POLACK FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603-2615. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577.

RENIA L, Goh YS, Rouers A, Le Bert N, Chia WN, Chavatte JM. Lower vaccine-acquired immunity in the elderly population following two-dose BNT162b2 vaccination is alleviated by a third vaccine dose.Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 8;13(1):4615. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32312-1.

SECRETARIA DE ESTADO DE SAÚDE (PA). Plano estadual de saúde do Pará. 2012. Available from: https://www2.mppa.mp.br/sistemas/gcsubsites/upload/37/PES-2012-2015.pdf. Aceso em: 11 nov. 2022.

SECRETARIA DE SAÚDE PÚBLICA (PA); Governo do Estado do Pará [internet]. Coronavírus no Pará. 2022. Available from: https://www.covid-19.pa.gov.br/#/

WU Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr 7;323(13):1239-1242. Available from: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. PMID: 32091533.

1 Pós-graduanda em Gestão da Qualidade em Saúde e Segurança do paciente – Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA). E-mail: karinehoronatosantos@gmail.com

2 Graduado em Enfermagem – Centro Universitário da Amazônia (UNIESAMAZ). E-mail: gabrielfurtadosdc@gmail.com

3 Pós-graduada em Unidade de Terapia Intensiva (UNIESAMAZ). E-mail:kellyalexandre16.com@gmail.com

4 Graduado em Nutrição – Centro Universitário do Pará (CESUPA). E-mail:viniciussodr@yahoo.com.br

5 Graduado em Enfermagem – Faculdade Pan Amazônica . E-mail: eliascostaufpa@gmail.com

6 Acadêmica de Enfermagem – Centro Universitário da Amazônia (UNIESAMAZ). E-mail:anacmpacheco@gmail.com

7 Acadêmica de Enfermagem – Faculdade Cosmopolita. E-mail:rayssalopes.jesus@gmail.com

8 Doutora em Doenças Tropicais (UFPA). E-mail:claudiam.moreira45@gmail.com

9 Mestre em Saúde da Família – Centro Universitário UNINOVAFAPI. E-mail:sabrinaaraujo.gmc@hotmail.com

10 Doutora em Biologia Parasitaria (UFPA). E-mail:cristalmesquita@yahoo.com.br