REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7826587

Eliene Pereira da Silva Dias¹

Nélia de Souza Mayrink Resende²

Edna Gomes Lopes da Cunha³

Sandra Terezinha Resner Manhães4

Abstract

Before the advent of the global phenomenon of the Covid 19 pandemic, the Brazilian formal education, within the school institution, was going through constant reflections about its objective function, envisioning fulfillment of the official documents to which it is subjected, moreover with deficiencies in various areas, and that had its intensification with the global phenomenon of the pandemic COVID-19. Thus, Brazilian education is in the process of transformation, needing to be rethought. Considering these nuances and proposing others, the present article aims to reflect on education in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, pointing out the challenges encountered, as well as presenting possible alternatives for a better and more effective new beginning, to collaborate with the transformation of the school into a learning space, in which teachers and students become autonomous in the construction of knowledge. The article is characterized as an essay, as it is structured to promote reflection and discussion on issues that still need more studies and debates to analyze the effects of the coronavirus on Brazilian education. The study concludes that by respecting social differences and overcoming other technological challenges, online teaching works as an important tool that provides access to education for students around the world, however, schools need to adapt. There is, therefore, a call to give new meaning to the educational process in Brazil, considering the issue of initial and continuing education for teachers so that they can seek, in the exercise of their function, to develop with competence and commitment to the evolution of effective work with students, in their integral formation.

Keywords: Education; COVID-19; Comprehensive Training; Educational Technologies;

1. Introduction

The worldwide phenomenon of the COVID-19 pandemic that devastated the world from 2019 onwards, had repercussions on all the limits of society, including, without a doubt, the field of education, which had to quickly transform and adapt to reality through the remote mobilization to contain the spread of the virus, adapting its educational activities to emergency teaching (Cardoso et al., 2020, p. 42; Cordeiro, 2020, p. 2).

However, when moving towards this “new normality” it is necessary for the school to rethink the teaching process, taking advantage of the challenges and lessons learned during the pandemic. In this context, universities and other educational institutions, as well as the training centers, made their training available through digital platforms, so that students, with or without previous experience in online training, could be immersed in non-face-to-face classes, in the sense of “continuing the lessons” (Jesus, 2021, p. 29).

From this perspective, the pandemic was responsible for changing not only people’s social lives, but also the teaching model, without, however, having defined a plan. Spalding et al (2020, p. 6) highlight that with the advance of the pandemic, it became necessary to adapt the education system, “so we sought to implement, not only solutions that could meet the needs of the moment”, but this it has been used to “promote a total disruption in the traditional teaching-learning process” (Spalding et al., 2020, p. 6). This is necessary for all students to continue the learning process. Current pedagogical practices have been aimed, above all, at the transmission of knowledge, the pandemic has shown that it is necessary to reflect on the “conception of teaching and learning and the need for engagement of all actors involved in the process” (Spalding et al., 2020, p. 20).

Despite attempts to change this reality, the teaching-learning process has been working as a cause-and-effect relationship, the so-called “banking education”, which takes place in a predictable and controllable environment. This model was impacted during the pandemic, where new educational technologies became part of the educational scenario.

From reflections on alternative emergency strategies found to develop educational actions during the Covid-19 pandemic, specifically in Brazil, questions emerge about new school teaching practices, which may become reality, from now on.

Therefore, this article aims to stimulate reflections from the panorama about the educational context in Brazil and the process of digital transformation, focused on the reality and expectations after Covid-19, showing the challenges encountered, as well as presenting possible alternatives for a better and more effective fresh start. In this sense, this work aims to rethink the school as a learning space for students to become autonomous in the construction of knowledge.

The proposed article uses the perspective of one of the most troubled periods experienced by the population of the most different age groups and social classes, in Brazil and the rest of the world.

The concern for the maintenance of life prevailed and so everyone was called to care and isolation. From there, the concern shifted to continuity and adaptation, and in the case of education, the need for protagonism in the training process arose, since both teachers and students had to let go of the conventions of the classic school institution since, in this new scenario, they needed to reinvent themselves and adapt.

With this perspective and the intention of discussing post-COVID-19 pandemic education, this article qualifies as an essay, considering that everyone was submitted to different protocols imposed by the pandemic, and we are still experiencing the impacts of this disease, so it is necessary to understand the various obstacles, solutions, and policies that have been adopted in Brazilian education and to consider the impacts experienced by the school, teachers, educational managers, students and parents in the process of continuing education and the leading role in the construction of knowledge.

The question that sews the reflections in this essay article is: What are the relevant aspects experienced by the school in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic that gave rise to political and pedagogical discussion to re-signify integral and autonomous formation within the scope of Brazilian educational system?

This essay is structured in seven parts, in addition to this introduction: the panorama of education in Brazil in the context of the pandemic is presented in the second topic; the third is the approach to aspects related to the practices adopted by the school to face Covid-19. In the following topics, the return to school activities after the release of the social isolation of Covid-19 gains space in the discussion; as well as the reflection on the expectations and perspectives of the school after the pandemic; with an approach involving innovations in the educational scenario post 2022 and, finally, final considerations are presented.

2. Overview of education in the context of Covid-19

At First, it is necessary to consider the pandemic context that devastated the world in November 2019. From that period until now, at the beginning of 2022, Brazil and the rest of the world are still trying to adjust to a reality caused by a virus that became known worldwide as “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), sometimes known as “Wuhan coronavirus”, about the city of Hubei province in China, where the first case of the disease occurred; or simply the Covid-19 virus, which gave rise to the Covid-19 disease (Latinne et al., 2020, p. 2).

This is a contagious and highly lethal virus, and is therefore the cause of the pandemic apex in the period 2019 to 2022. Preliminarily, it was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO), as a “public health emergency of international concern, and then as a pandemic, considering the infectious characteristic of the disease.

The symptoms of Covid-19 are the most varied. Among the most common are fever, fatigue and breathing difficulties, which can lead the patient to death. Contagion and its proliferation were the biggest justification for infected countries to enact preventive measures such as social distancing, lockdowns, the use of face masks, monitoring and development of medicines and vaccines, as well as immunization campaigns to inhibit the devastating effect of the virus (Aquino et al., 2020, pp. 2425–2428; Brasil – MS, 2020; Soares et al., 2021, p. 9).

This brief history is justified in this file to show how impetuous the Covid-19 virus has been. Its devastating effect has brought fear, terror, and panic in the face of the impotence of health authorities to stop the devastating advance of Covid-19, as well as the lack of hospital capacity to care for those affected by the disease whose medical protocols were being developed and studied as the virus spread. In addition to the lack of structure of the hospital systems, the suffering and mourning installed in society with the death of loved ones and friends, leaving families desolate.

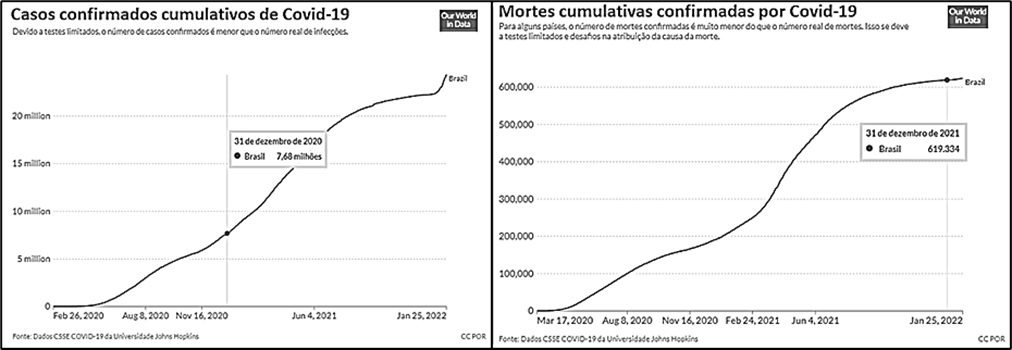

Figure 1 shows a map of Covid-19, highlighting an accumulated total by December 31, 2021, more than 7 million confirmed cases and more than 619,000 confirmed deaths in Brazil.

Source: (Ritchie et al., 2020)

Figure 1 – Situation of Covid-19 in Brazil until 31.12. 2021

In Brazil and the rest of the world, people were advised to follow preventive measures, among which the use of face masks, the use of alcohol gel for hand hygiene, and social isolation stand out (Aquino et al., 2020, p. 2454; Brasil CNS, 2020). These factors strongly impacted the modus operandis of the Brazilian educational system, as this meant a break in pedagogical planning, the interruption of school activities, and the drastic closure of schools.

According to the United Nations (2020), the closing of schools, despite protecting children and young people from the virus, implies the interruption of the learning process for those in high vulnerability situations and increases the risk of augmenting school dropout rates, which may generate a significant drop in the level of human capital in the future, in addition to harming the social protection network due to the interruption of school meals and the accumulation of work and care by women (Silva & Sousa, 2020, pp. 967, 968).

Now, it is obvious that no one and no nation was prepared to face a pandemic of the scale of Covid-19. However, the most developed countries quickly organized themselves to prevent the spread of the disease. Workers were laid off, while others worked remotely. Schools were forced to close their doors (Dias & Ribeiro, 2020, p. 3). In this sense, while private schools quickly adapted their teaching modality to serve students virtually, public schools, given their characteristics, took a little longer to understand that it was necessary to remodel the teaching format and, thus, define how to follow, to avoid the total loss of the school year.

Students and families were faced with a new reality, in which the educational routine came to depend on parents, who in addition to adapting to remote work, now needed to help their children in their virtual teaching activities. The students also needed to adapt to being away from school and, in order to continue their studies; they had to remodel their routine to adapt to the new class format (Cordeiro, 2020; Dias & Ribeiro, 2020, p. 2).

At that moment, the guidelines and paradigms experienced by education professionals gained focus. The spotlights that Covid-19 threw on education revealed some ills of the Brazilian educational system, highlighting the (in)capacity of many schools to adapt, the failures of the evaluation process, and the difficulties of teachers in formatting a new, more inclined posture towards technology and less focused on the brush, whiteboard and data show, according to Jesus (2021) “many teachers were not prepared to include new technologies, considering that their training does not include the use of digital technologies”(p. 19). From this perspective, Silva and Souza (2020) also note that:

[…] the pandemic is a wake-up call for the creation, expansion, and consolidation of digital inclusion policies in everyday school life; the valorization of learning through media; application of educational software; assistance in the acquisition of notebooks/computers; the availability of flash drives; assistance in contracting data packages/internet services; the implementation of teleconferencing services; the creation of telecenters and Technological Vocational Centers; the offer of workshops, training, and qualification/improvement courses to optimize the use of technological resources, etc (Silva & Sousa, 2020, p. 972).

From this overview, it can be said that the pandemic revealed the need to include schools in the digital world, evidencing the lack of initial and continuing training, which occurred almost instantly at the beginning of the pandemic, revealing the inability of many teachers in the use of digital technologies in classes, showing the comfort of traditional education, where the figure of the teacher is still centered as a transmitter of knowledge, thus characterizing the passivity of the student, which corroborates the deficiencies of the educational system (Cordeiro, 2020, p. 4).

This movement also revealed the need for implementation of educational policies to develop countermeasures in order to structure schools, teachers, and students in the challenge of building knowledge in the face of the appropriation of information and communication technologies to promote knowledge and the search for the improvement of the school learning level, in addition to strengthening school interactions.

In the next topic, the actions adopted by the school, based on the government’s guidelines, to face this scenario that has been imposed since the first months of 2020 and has lasted until now are the subject of reflection and discussion.

3. Actions taken by schools to face Covid-19

Following recommendations from the World Health Organization, Brazilian authorities decreed the lockdown, in March 2020, as the first measure to combat Covid in schools. Thus, with no time to react, the educational institutions were closed, being challenged to review their planning to promote the continuity of studies during social isolation. In this sense, to restructure the way of working it was necessary to evaluate a new teaching format to meet the urgent need imposed by the pandemic (Silva & Teixeira, 2020, p. 7071).

At that time, the government, through the Ministry of Education, established regulations in order to regulate and guide educational activities. Then was published the Portaria Mec nº 343/2020 (Brasil-MEC, 2020) which provided for the replacement of face-to-face classes by digital classes, while the pandemic lasted. At the same time, the National Education Council (CNE) presented in March 2020 a proposal for an opinion on the reorganization of school calendars and the realization of non-presential pedagogical activities. Also, in April 2020 the CNE approved Guidelines for schools during the pandemic, providing guidelines for basic education and higher education.

However, difficulties of all kinds soon arose, such as the social abyss, failures in the planning process, and lack of infrastructure, among others.

During the pandemic, schools had to provide technological support to students to continue pedagogical activities, through social networks, messaging apps, and e-mail. In addition, some public and private initiatives promoted the donation of electronic equipment (computers, notebooks, and smartphones) for student use, and some virtual classroom platforms expanded free access during this period, such as Zoom and Google Meet.

Among the strategies adopted by schools with teachers, the holding of virtual meetings for planning and coordination of activities, as well as training in the use of non-presential teaching methods and materials, stand out. Flauzino et al (2021, p. 3) emphasize that “these alternative strategies need to be accelerated”, according to these researchers, “the pandemic served as a springboard” for educational institutions to appropriate technology in the educational field.

There is no denying the effort to avoid the disruption of teaching and the continuity of classes, but not all schools were reached, not all students and teachers had access to technological resources, nor to Internet connections. Not all teachers have been trained to develop classes in the virtual format, have not all strategies been implemented.

3.1 Remote teaching and the appropriation of information technologies and educational digital resources

With the interruption of classes, mentioned above, educational institutions, whether public or private, continued their educational activities through online education platforms.

Just like companies that, during the pandemic, started to hold meetings via online platforms, educational institutions had to replace face-to-face classes with classes in digital media. This situation exposed the weaknesses and strengths of the educational system and its ability to adapt and reinvent itself. However, it is important to highlight the precarious technological reality of students, educators, and schools themselves, for the continuity of the teaching and learning process. After all, no one was prepared for this time of technological immersion in Brazilian schools, especially public ones.

[…] the use of these same technologies in basic education is a bigger problem because schools are not prepared, but he argues that educational institutions should use and adapt to these new technologies more quickly. On the other hand, we are faced with another problem, for these practices to be effective and democratic, he argues that all students must have access to the internet. (Barreto & Rocha, 2020, p. 9).

The authors Barreto and Rocha (2020) explain that social inequalities were accentuated, although they have always been perceived in the Brazilian educational system.

According to a survey carried out in 2019 by the Regional Center for Studies for the Development of the Information Society (CETIC), when talking about students from private schools, the percentage of students who have access to a computer at home is 91%, while for the public-school students, this number drops to 61%.

Social inequalities are also manifested in the digital environment, with the potential to restrict opportunities and even conditions for compliance with measures to combat the pandemic. […]. This highlights the multiple layers of inequality and their combined effects on the use of digital opportunities by different segments of the population (Cetic, 2020, p. 4).

Cardoso, Ferreira, and Barbosa (2020, p. 39) wrote that the pandemic reinforced the social inequality of access and quality of Brazilian education. Stevanim (2020) explains that “the pandemic does not only make teaching difficult because of the problems of access to digital technology by a portion of students – the role of the school as a space for interaction and development is also affected” (p. 11).

It is evident that the unprecedented scenario, experienced due to the pandemic, forced the world to review new ways, as well as possibilities to continue studies. Barreto and Rocha (2020, p. 5) citing Santos (2020, p. 21) emphasize that the pandemic not only highlights injustices, “but reinforces injustice, discrimination, social exclusion and the undeserved suffering they cause”.

Despite all these reflections, the strategy was adopted and the schools organized themselves to migrate to remote teaching with the use of digital methodologies, generating the “transposition of practices and methodologies from face-to-face teaching to virtual learning platforms, the so-called remote teaching” (Souza, 2020, p. 113).

It can be noticed without a doubt that, because of this process, there was an acceleration in the process of digital transformation, which is increasingly present and exponentially growing in the school context during the pandemic. The so-called “remote teaching” lasted for long months during isolation and became a challenge for teachers who needed to be equipped to use the tools to develop their classes, generating anxiety and technical difficulties for teachers, in addition to work overload (Souza, 2020, p. 113).

The implementation of hybrid education has become a reality, however, with many obstacles in most public schools, evidencing the need for schools to be connected not only in networks but also to the difficulties of teachers and students, as well as managers. and the pedagogical teams in this process of adaptation to the new roles required for human development today (Cardoso et al., 2020, p. 44).

Another relevant aspect was the participation of parents and family members in the education of their children at home. This implied both the parent’s ability to use Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and being able to guide their children, as well as the time available, given the parents’ work is also remote.

Also, in the first moments of adaptation, it was observed that there was no training and time to change the format of classes for emergency remote teaching, and the change happened only in the modality of presential classes for virtual rooms. Other professionals needed to seek qualifications to handle ICTs programs and applications and, thus, to appropriate a language of their own in the virtual environment, in addition to being challenged not only to present the content more dynamically and engagingly but also to produce content and more interactive activities.

There are many challenges and (im)possibilities for teaching practice in the current context, it is observed that teachers are more consumers of technology than producers. This fact is due to the initial training model that needs to be thought/adapted to the contemporary world (Barreto & Rocha, 2020, p. 9).

Silva and Souza (2020) emphasize that the pandemic has become a vehicle “to visualize, even more, education as a fundamental right that takes into account equality and the issue of difference”, according to these authors, differences are associated with the affirmation of equality, since “equality is not opposed to difference, but inequality” (p. 13).

Given the actions taken by the school to face the social isolation imposed by the fight against the proliferation of Covid-19 in the educational context, other unique issues arose with the pandemic and brought to light the need for training teachers, due to the new educational model that was being outlined for this new society. According to Bedarida (2002, p. 221) the “history of the present time is made of provisional abodes”, in this vein, the model strongly evidenced today, has been demanding from the education professional, both the managers as for the teachers, an attitude inclined to re-signify history, having as a background the contemporaneity and the consequently abrupt changes arising from it.

It is necessary to highlight the excess work that education professionals were subjected to, resulting from these changes, especially the overload in the emergency transition from presential to remote teaching, where many professionals had to improvise their work, including looking for courses to meet the lack of adequate training for their performance in the new pandemic scenario.

Terms previously unimaginable to teachers, “knocked on the door” and could be heard in all corners of the world, terms such as innovation, and cyberculture, once used by technology professionals, began to be part of the work in education, as the new space of contemporary civilization. Thus, this aspect, related to the forms of organization to which the school had to be submitted, with its previously presential communities and in the current conjuncture organized in virtual communities, brings the concept of cyberculture, proposed by Levy (2011, p. 130), as “the expression of the aspiration to build a social bond” from virtual communities that are not limited to territorial ties, nor to institutional or power relations, but are considered in common interests, knowledge sharing, cooperative learning and open collaborative processes.

Certainly, these virtual communities, which are configured as networks of relationships, where people get together, regardless of distance, aiming at forms, which even for the author, in addition to places where people meet, virtual communities are also tools for work and for information search.

Given the above, this entire context of digital inclusion needs to meet the needs of students, teachers, as well as pedagogical teams in general. Thus, just the use/access to a digital device does not guarantee this inclusion, as not everyone has access to this equipment.

The student is no longer the receiver of information to become responsible for the construction of his knowledge, using the computer to search, select, and interrelate significant information in the exploration, reflection, representation, and debugging of his ideas, according to his style of thought. Teachers and students develop actions in partnership, through cooperation and interaction with the context, the environment, and the surrounding culture (Santos & Radike, 2005, p. 328).

Access to the internet is essential, but in addition to this issue, it is essential to think about its actual use, as well as the mastery of digital media, so that the use of resources happens entirely. Only then, students will there be the possibility to develop their learning and thus be able to overcome barriers to build the knowledge based on critical thinking.

4. Return to school activities after release from Covid-19 social isolation

As previously discussed, the social isolation resulting from Covid-19 greatly affected the relationships maintained between people, thus forcing the creation of new habits, due to the uncertainties arising from this process. In fact, during a pandemic, people are in a frequent state of alert, worry, stress and a feeling of lack of control in the face of the uncertainties of the moment.

Thus, after long months, under this scenario, the timid initial return to face-to-face activities took place. Cardoso, Ferreira and Barbosa (2020, p. 45) explain that the return to face-to-face classes, even in a hybrid form, favors connectivity and inclusion, this requires planning, vision and care.

This return to face-to-face work required different forms of organization that would minimally enable the definition of strategic goals, such as welcoming and gradual return plans, which should observe health protocols of general guidelines for combating and preventing Covid-19, including social distancing.

To welcome is to welcome, admit, accept, listen to, give credit to, wrap up, receive, attend, and admit (FERREIRA, 1975). Reception as an act or effect of welcoming expresses, in its various definitions, an action of approximation, a “being with” and a “being close to”, that is, an attitude of inclusion. This attitude implies, in turn, being in a relationship with something or someone. (Brasil-MS, 2010, p. 6).

The school plays a fundamental role in the socialization and formation of individuals; therefore, for this return it was necessary to consider the necessary security to favor the most diverse demands, with the issues socio-emotional being one of the most important. The general guidelines of the National Common Curricular Base (BNCC) (Brasil – MEC, 2018) determine that schools need to develop competencies in this area. Taking into account the pandemic context experienced in this time, these skills are very important and cannot be left aside. Assuming that the school environment is the institutionalized stage, where the indispensable interactions take place for the human being to be constituted from differences, exchanges of experiences, values, and interests.

In view of the above, it brings reflections on the role of the school after the pandemic to the current scenario, especially with regard to the reception and revision of curricula. It is emphasized that the curriculum must be impregnated with sense and meaning so that it is really alive and expresses the reality of the school community and also promotes the student’s protagonism, privileging innovation as a tool in the face of new challenges, which are certainly a source of multiple analyzes and discussions.

Still reflecting on Arendt’s (2007) thought, the role of the school as a promoter of interaction for the development of being is evidenced. From this perspective, education, in this institutionalized space, plays a leading role in the “resumption” of post-pandemic life, given the urgency and responsibility for the particularities that form the collective, according to Arendt (2007, pp. 15–16), plurality is the condition of human action because we are all the same, that is, human, without anyone being exactly the same as anyone who has ever existed, exists or will exist.

In this sense, it is considered possible to have “Education as a reinvention of post-pandemic life”. To this end, it is necessary to reflect on the role of the school for the current period, therefore, going beyond the banking model of teaching, where the student becomes a mere depository of the teachers’ knowledge (Freire, 1987, p. 38).

[…] for the most part, classrooms still have the same structure and use the same methods used in 19th-century education: curricular activities are still based on pencil and paper, and the teacher still occupies the position of protagonist principal, holder, and transmitter of information (Valente, 2014, p. 142).

Thus, it is worth bringing to the discussion this educational model that prevailed for a long time, but currently unthinkable. This discussion gained strength due to the pandemic, where the protagonism of the student must prevail, in addition to other issues such as the implementation of new methodologies, such as the inclusion of new educational and digital resources, because, as Freire (1987, p. 38) highlights “liberating” or “problematizing” teaching, which encourages students to actively participate in learning and, above all, questioning reality, in order to intervene in it.

Still under this premise, for the school to be restructured it is necessary to rethink old habits, allowing an openness to the demands arising from this new moment that calls for changes in the use of active methods, with the use of digital technologies and the adoption of new teaching models. , this implies expanding investments in initial and continuing teacher training and in infrastructure to meet current needs.

5. Expectations and perspectives of the school, post-Covid-19

Faced with the scenario resulting from Covid-19, combined with the complex and delicate aspects that permeate Brazilian education for a long time, it is necessary to reflect on important issues for education, in the sense of valuing the learning acquired through the experience of the pandemic and, thus, , moving towards a better and more effective school.

From this perspective, in the first place, it is necessary to rethink public policies, so that they really involve the different social classes, given the high rate of failure and dropout of students from less favored social classes. Secondly, it is essential to adopt a curriculum that includes comprehensive and consistent training for students, and finally, teacher training requires a more conscious attitude towards the role of education in contemporary times.

The role of public policies, then, would be to promote equity, addressing binomial access and permanence. Thus, to provide conditions for access to the historical heritage of humanity, privileging “learning to learn”, here understood as a function of the school to allow the development of the potential of the being, as an individual.

Welcoming new people into the world, therefore, presupposes a double and paradoxical commitment on the part of the teacher. On the one hand, it is up to them to ensure the durability of the world of symbolic inheritance in which they initiate and welcome their students. On the other hand, it is up to them to ensure that the new ones can learn about, integrate, enjoy and, above all, renew their public heritage that belongs to them by right, but whose access is only possible through education . (Carvalho, 2006, p. 57).

As can be noticed, this author, Carvalho (2006), interprets the role of the teacher as an agent responsible for both reception and care. In the wake of these reflections, it is salutary to highlight the true education impregnated with meaning, and for that, individual values, based on the premise that it is through singularity that the whole is formed, complex and that is articulated in the formation of the new that emerges each day.

5.1 Innovations and Perspectives in the Educational Scenario after the 2019 pandemic

Predictions for education after the pandemic, starting in 2022, follow from the perspective of analysis and reflection by scholars in the area, precisely because the effects generated by Covid-19 will continue to interfere in the daily life of schools, creating challenges for the entire community. school community. Although vaccination has already reached all Brazilian states, the variants of the coronavirus make it difficult to fully immunize the population, and thus, there are still many fears and uncertainties.

Despite all this, it is undeniable that the digital transformation that enabled the new structure of the school in this pandemic period, brought new forms of coexistence and re-elaboration of the curricular structure, therefore, new perspectives were launched, with emphasis on hybrid teaching, in its modality disruptive that includes the modalities of inverted classroom, flex, rotational laboratory, à la carte and by seasons (Cecílio, 2020, pp. 3–4).

Briefly discussing these modalities, Cecílio (2020, pp. 3–4) explains how these modalities can be used in the educational field. The flipped classroom happens as follows: The student studies the class material before the presential meeting and already brings information to dialogue and deepen their knowledge, with the teacher and colleagues as mediators of this process.

Concerning the Flex model, the role of the student comes into play again, putting the teacher in the position of tutor and mediator to answer questions, as well as organize the study, and studies, which can vary between individuals and groups.

In the Rotational Laboratory, the class is divided into two groups, one part carrying out the online activities and the other having the support of the teacher in the classroom. That is, the student has autonomy about studies supported by digital technologies, where he can count on the support of the teacher in person. Thus, it is observed that in the different models presented, there is the figure of the teacher as a mediator of knowledge and the student as the main actor (Cecílio, 2020, p. 3)

In addition to these teaching modalities, other digital resources were inserted into the educational context. One of these resources was gamification, which use of game design techniques that use game mechanics and game-oriented thoughts to enrich diverse contexts normally unrelated to games. Navarro (2013) states that games precede culture and are part of human coexistence and relationships.

When considering the game inherent to man and precedent to culture, it is understood that the mechanisms of games are present in the way of living and relating to human beings since the beginning of civilization. Survival itself can be considered a way of playing with life and, therefore, gamification cannot be understood as something new in society. Like the game, gamification still does not have a definitive and exact concept, but it has been understood by game theorists and developers as the application of game elements, mechanisms, dynamics, and techniques in the context outside the game (Navarro, 2013, p. 17).

The term gamification intensifies aspects such as engagement, motivation, and creativity, expressions that are increasingly frequent in gaming experiences. Costa and Marchiori (2015, p. 48) citing Werbach and Hunter (2012) explain that these authors classify elements of gamification into three categories: dynamics, mechanics, and components.

The dynamic is about emotional arousal to the players’ interest; and involves elements such as narrative, progression, relationships, and constraints. Mechanical elements are those that restrict the game and guide the participants; evaluation, odds, feedback, cooperation and competition, challenges, rewards, and others. Components are the most specific and concrete applications of gamification elements and include avatars, virtual goods, achievements, unlockable content, badges, medals, graphics, missions, levels, points, and others. It is probably these aspects, of these experiences that influenced the applicability of the game in the educational context.

Henceforth, it is necessary to recognize that in addition to the inclusion of novelties and technologies, a change in the way of understanding knowledge is also fundamental. From this perspective, there are many prerogatives brought about by the use of ICTs, and they design a new style of teaching and learning. Again, the National Curricular Common Base is presented, which includes, within two competencies, digital culture, which reinforces the use of ICTs for this purpose.

It is worth remembering that the devices, tools, applications and different platforms, which supported remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, made it possible to expand opportunities for reinventing post-pandemic education, becoming fundamental actions to leverage and occupy new virtual spaces, which were strongly configured throughout this period.

Furthermore, as already mentioned, this time we will have as allies parents and family members who have developed skills in the use of ICTs and also teachers and education professionals who sought qualifications to handle ICT programs and applications, making their classes more dynamic and interactive.

6. Final considerations

This article addressed the panorama of Brazilian education, from the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, in which educational institutions had to unexpectedly adopt strategies for the continuity of teaching activities, that is, from the face-to-face model to remote teaching.

This essay sought to show the experiences lived with the pandemic, as well as to glimpse possibilities and perspectives to be considered in order to reframe the process of integral formation, at school and outside of it, as a result of this experience, rethinking the school as a learning space for students to become autonomous in the construction of knowledge.

The main objective of this essay-type article was to provoke reflections from the panorama on the educational context in Brazil and the process of digital transformation, returns to reality and post-Covid-19 expectations, showing the challenges encountered, as well as presenting possible alternatives for a more effective restart.

The need to reinvent educational life in the post-pandemic period was also highlighted, since the teaching and learning process yearns for changes and thus, in a positive way, adopting as active methodologies the use of technological resources that facilitate learning, as well as as improvement of pedagogical and didactic practices.

In this vein, it is necessary to adopt new ways to provide students with resources that make classes more exciting, while allowing more autonomy for student learning. In this way, the need to equip schools was glimpsed, with investments in infrastructure, in technological resources and, therefore, in the continuing education of education professionals.

There is still a long way to go for institutions, some important reflections such as the reformulation of public policies aimed at teacher training, the curriculum for comprehensive training, the human training of education professionals and students, access to the use of massive technology, among other aspects that are essential to enrich the debate and transform educational spaces, especially thinking about the public school and the equality of education provided for in the Federal Constitution of 1988, as well as other official documents that govern Brazilian education.

Finally, in the course of all the questions raised, based on the experience of the Covid-19 pandemic, the debate for the improvement of Brazilian education has become rich and emerging, giving rise to new studies that consider the perspectives that involve the improvement of the educational processes to improve the teaching and learning process.

It is concluded, therefore, that there is a need to reflect on past experiences, considering the impact of the pandemic on all sectors of the global community and thus, to see, in addition to the undeniable losses and damages experienced in the context of Covid-19, the possibilities of solid changes, in order to (re)build a new moment in the face of the basic needs of education in the country and envision the qualitative improvement of educational processes in Brazil.

7. References

Aquino, E. M. L., Silveira, I. H., Pescarini, J. M., Aquino, R., & de Souza-Filho, J. A. (2020a). Medidas de distanciamento social no controle da pandemia de COVID-19: potenciais impactos e desafios no Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25, 2423–2446. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.1.10502020

Arendt, H. (2007). A condição humana (10th ed.). Forense universitária. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/A condição humana- Hannah Arendt.pdf

Barreto, A. C. F., & Rocha, D. S. (2020). Covid 19 e educação: resistências, desafios e (im)possibilidades. Revista Encantar, 2(1), 01–11. https://doi.org/10.46375/ENCANTAR.V2.0010

Bedarida, F. (2002). Tempo-presente-e-presenca-da-história. In FGV (Ed.), Uso e abusos da história oral (5th ed., pp. 219–229).

Recomendação CNS n.36 de 11.5.2020, Conselho Nacional de Saúde (2020). http://conselho.saude.gov.br/images/Recomendacoes/2020/Reco036.pdf

Brasil – MEC. (2018). Base Nacional Comum Curricular – Educação é a Base. Ministério Da Educação. http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/abase/#introducao

Portaria no 343-20-MEC, Pub. L. No. 343, . Planalto.gov (2020). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Portaria/PRT/Portaria no 343-20-mec.htm

Brasil – MS. (2020). Acha que está com sintomas da covid-19? – CORONAVÍRUS. Ministério Da Saude. https://www.coronavirus.ms.gov.br/?page_id=29

Brasil-MS. (2010). Núcleo Técnico da Política Nacional de Humanização. Acolhimento nas práticas de produção de saúde (Ministério da Saúde, Ed.; 2nd ed.). Ministério da Saúde. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/acolhimento_praticas_producao_saude.pdf

Cardoso, C. A., Ferreira, V. A., & Barbosa, F. C. G. (2020). (Des)igualdade de acesso à educação em tempos de pandemia: uma análise do acesso às tecnologias e das alternativas de ensino remoto. Revista Com Censo, 7(3), 38–46. http://www.periodicos.se.df.gov.br/

Carvalho, J. S. F. de. (2006). Acolher no mundo: educação como iniciação nas heranças simbólicas comuns e públicas. In Editora Unesp (Ed.), Formação de Educadores: artes e técnicas, ciências políticas.Raquel Lazzari Leite Barosa (org.) (pp. 53–60).

Cecílio, C. (2020). Ensino híbrido: quais são os modelos possíveis? Nova Escola, 4. https://novaescola.org.br/conteudo/19715/ensino-hibrido-quais-sao-os-modelos-possiveis

Cetic. (2020). Pesquisa TIC Domicílios 2020. www.grappa.com.br

Cordeiro, M. K. A. (2020). O impacto da pandemia na educação: a utilização da tecnologia como ferramenta de ensino. Faculdades IDAAM, 15. http://repositorio.idaam.edu.br/

Costa, A. C. S., & Marchiori, P. Z. (2015). Gamificação, elementos de jogos e estratégia: uma matriz de referência. InCID: Revista de Ciência Da Informação e Documentação, 6(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2178-2075.v6i2p44-65

Dias, B. G., & Ribeiro, G. A. M. (2020). A educação remota em tempos de pandemia: discutindo os processos ensino-aprendizagem e as flexibilizações dos processos educativos. Anais Do CIET:EnPED:2020 – (Congresso Internacional de Educação e Tecnologias | Encontro de Pesquisadores Em Educação a Distância), 9. https://cietenped.ufscar.br/submissao/

Flauzino, V. H. de P., Cesário, J. M. dos S., Hernandes, L. de O., Gomes, D. M., & Vitorino, P. G. da S. (2021). As dificuldades da educação digital durante a pandemia de COVID-19. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo Do Conhecimento, 05–32. https://doi.org/10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/saude/educacao-digital

Freire, P. (1987). A pedagogia do oprimido (Paz e Terra, Ed.; 17a). Paz e Terra. https://doi.org/10.1088/1751-8113/44/8/085201

Jesus, P. T. N. de. (2021). Impactos educacionais causados pela pandemia [UniAGES Centro Universitário]. https://repositorio.animaeducacao.com.br/bitstream/ANIMA/14873/1/Monografia – Pamala.pdf

Latinne, A., Hu, B., Olival, K. J., Zhu, G., Zhang, L., Li, H., Chmura, A. A., Field, H. E., Zambrana-Torrelio, C., Epstein, J. H., Li, B., Zhang, W., Wang, L.-F., Shi, Z.-L., & Daszak, P. (2020). Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. NUS Medical School, 7, 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3

LEVY, P. (2011). O que é o Virtual? Trad. Paulo Neves. Coleção Trans. 2a Edição. (Vol. 1). Editora 34. http://bit.ly/3KdLhPW

Navarro, G. (2013). Gamificação: a transformação do conceito do termo jogo no contexto da pós-modernidade [USP]. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/

Ritchie, H., Mathieu, E., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Giattino, C., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Beltekian, D., & Roser, M. (2020). Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Brasil: Perfil do país da pandemia de coronavírus – Nosso mundo em dados. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/brazil

Santos, B. S. dos, & Radike, M. L. (2005). Inclusão digital: reflexões sobre a formação docente. In DP&A (Ed.), Inclusão digital: tecendo redes afetivas/cognitivas.

Silva, D. dos S. Vasconcelos., & Sousa, F. C. de. (2020). Direito à educação igualitária e(m) tempos de pandemia: desafios, possibilidades e perspectivas no Brasil. Revista jurídica luso-brasileira, 6, 961–979. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/consti-

Silva, C. C. S. C. da, & Teixeira, C. M. de S. (2020). O uso das tecnologias na educação: os desafios frente à pandemia da COVID-19 / The use of technologies in education: the challenges facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian Journal of Development, 6(9), 70070–70079. https://doi.org/10.34117/BJDV6N9-452

Soares, K. H. D., Oliveira, L. da S., da Silva, R. K. F., Silva, D. C. de A., Farias, A. C. do N., Monteiro, E. M. L. M., & Compagnon, M. C. (2021). Medidas de prevenção e controle da covid-19: revisão integrativa. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde, 13(2), e6071. https://doi.org/10.25248/reas.e6071.2021

Souza, E. P. de. (2020). Educação em tempos de pandemia: desafios e possibilidades. Cadernos de Ciências Sociais Aplicadas, 17(30), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.22481/ccsa.v17i30.7127

Spalding, M., Rauen, C., Vasconcellos, L. M. R. de, Vegian, M. R. da C., Bressane, A., Salgado, M. A. C., & Miranda, K. C. (2020). Desafios e possibilidades para o ensino superior: uma experiência brasileira em tempos de COVID-19. Research, Society and Development, 98(8), 23.

Stevanim, L. F. (2020). Desigualdades sociais e digitais dificultam a garantia do direito à educação na pandemia ‘Ninguém pra trás’. RADIS, 2015, 10–15. https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/43180/2/NadaRemota.pdf Valente, J. A. (2014). a Comunicação E a Educação Baseada No Uso Das Tecnologias Digitais De Informação E Comunicação. UNIFESO – Humanas e Sociais, 1(01), 141–166. http://www.revistasunifeso.filoinfo.net/index.php/revistaunifesohumanasesociais/article/view/17

¹SILVA-DIAS, Eliene Pereira da. Master in Governance and Development/Enap and PhD student in Educational Sciences/UTIC-PY. Specialist in People Management in the Public Service and in Executive Secretariat. Civil servant in the Brazilian federal judiciary. Email: eneiledays@gmail.com. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3918-0593

²RESENDE, Nélia de Souza Mayrink. Master in governance, technology and innovation/UCB. officer of Superior School of War – Ministry of Defense. Email: neliamayrink@gmail.com. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7011-5802

³CUNHA, Edna Gomes Lopes da. Specialist in Teaching Chemistry, Federal University of ABC, Specialist in “Distance Teaching” by Centro Universitário Sul de Minas. Professor at the Technical School of Paulínia. Email: ednacunha46@gmail.com. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3453-5305

4MANHÃES, Sandra Terezinha Resner. Specialist in Early Childhood Education from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Pedagogue from the University of the State of Santa, Tutor Professor of Undergraduate and Postgraduate courses in the area of Education, Teacher Literacy and Literacy and Early Childhood Education. Email: sandraresnermanhaes@gmail.com. Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7767-0721