REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10550889

Christiana Soares de Freitas¹;

Marco Konopacki²;

Jean Marcel da Silva Campos³.

Abstract

Latin American and Caribbean countries have been implementing digital democratic innovations (DDIs) since 1990, thereby expanding participation and diversifying voices within their political systems. Between 2010 and 2016, these initiatives doubled in number. However, by the year 2016, at least 36% of these initiatives had been discontinued. Nevertheless, with the onset of the pandemic in 2020, the number of democratic innovations, particularly digital ones, experienced a significant resurgence.

This article provides an overview of both the quantitative and qualitative transformations of digital democratic innovations in recent years, aiming to understand the relationship and interdependence between political contexts and the continuity – or lack thereof – of DDIs in the region. Within this article, we explore the critical need for formalization of these initiatives and the importance of diversifying the actors responsible for creating DDIs to ensure their growth, continuity, and sustainability. Concepts rooted in the theory of public action are applied.

Keywords: Digital Democratic Innovations; Latin America and the Caribbean; Theory of Public Action.

Introduction

Over the course of three decades, democratic innovations in Latin America have traversed a dynamic landscape of changing political environments, thereby shaping and evolving their characteristics and institutional frameworks. The article seeks to comprehensively analyze the impact of this scenario on the diverse contexts of creating democratic innovation projects, with a particular emphasis on digital democratic innovations (DDIs). The theoretical framework for this analysis draws from the sociology of public action (LASCOUMES; LE GALES, 2012).

In the first section, we present the contemporary debate on democratic innovations. In the following section, we discuss the political landscape in Latin America between 1990 and 2020, analyzing the contextual factors that have affected the creation of digital democratic innovations (DDIs) on the continent, a topic further explored in the subsequent section. Finally, we highlight the shift in the protagonism of DDIs’ creation, transferring from governments to civil society, and the challenges posed for the institutionalization of these initiatives.

Democratic Innovation and Participation

The end of the 20th century witnessed a redefinition of democratic theory, where citizen participation became a central concept for understanding ongoing political dynamics. Authors like Benjamin Barber (2003), who authored the classic “Strong Democracy,” as well as the work of Carole Pateman (1992) and Chantal Mouffe (2013), initiated reflections on participatory democracy. Other actors joined this debate, refining concepts or deriving new ones. The concepts of Participatory Institutions (AVRITZER, 2008) and Democratic Innovations (SMITH, 2009) emerged from extensive discussion in the field¹. Contemporary scholars in the field of Internet and Politics, with reflections on the influence of information and communication technologies on political processes and citizen participation have also contributed (SAMPAIO, 2011; GOMES, 2018; FREITAS; SAMPAIO; AVELINO, 2023).

Citizen political participation has become one of the central axes of political practices and strategies in various democratic countries, including those in Latin America and the Caribbean. Examples of this context are the democratic innovations identified and analyzed by the Latinno project², resulting in a database with information on 3,744 initiatives mapped in the region over a thirty-year period – from 1990 to 2020 (POGREBINSCHI, 2021). In addition to names, locations, levels of operation, and periods of operation, this database also contains information related to the institutionalization and the political and social results and implications of these initiatives.

The objective of this article is to analyze this data, with a specific focus on Digital Democratic Innovations mapped by the Latinno project, i.e., democratic innovations that utilize technological and communication resources to achieve their goals. To analyze the current scenario, we will discuss, in the first instance, the transformations observed over the years and the political factors responsible for these changes. The main explanatory factors to be mobilized include (1) the pandemic, which brought about changes in the quantity and quality of content offered by digital democratic initiatives; (2) political changes in various countries in the region that brought right-wing political groups to power, which has been considered a form of “neo-conservatism” or signs of democratic erosion (BIROLI; MACHADO; VAGGIONE, 2020); (3) socio-technical factors explaining changes in the design, continuity, and reach of DDIs, such as the use of artificial intelligence, open data, and collaborative law production practices (crowdlaw) to bring citizens closer to decision-making political processes.

In 2009, in his book “Democratic Innovations,” Graham Smith first introduced the term “democratic innovations” to refer to the opening of institutions for democratic practices. According to the author’s definition, democratic innovations represent “institutions that are specifically designed to increase or deepen citizen participation in the political decision-making process” (SMITH, 2009, p. 1). Beyond the initial classical conceptualization, Pogrebinschi, more recently, adopted a pragmatic approach in mapping and analyzing democratic innovations, as applied to the analysis of the aforementioned 3,744 mapped democratic innovations. This theoretical perspective defines democratic innovation as “institutions, processes, and mechanisms whose purpose is to enhance democracy through citizen participation in at least one stage of the policy cycle” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021).

In addition to this pragmatic understanding of the constitution and configuration of innovations, the approach based on the theory of public action suggests understanding democratic innovations as “sociotechnical spaces where knowledge, tools, processes, actors, and representations converge to materialize public action” (FREITAS, 2020). Digital democratic innovation, by its turn, is the “technologically mediated space with the same purpose, systematizing citizen demands and creating spaces of convergence among multiple actors involved in seeking solutions to specific public issues” (FREITAS; CAPIBERIBE; MONTENEGRO, 2020).

This perspective deepens studies on digital governance networks and their implications for the current configuration of networked society based on the theory of public action. It aims to understand governance, which is now permeated by internet-mediated political processes, suggesting analyses that view it as a fundamental instrument shaping power relations in contemporary society. The unique characteristic of the proposed public action approach is the comprehension of democratic innovations within the context of spaces constituted by multi-sectoral, multi-actor, diverse, and plural construction. Democratic innovations are seen not only as instruments that perform the mediation between citizen demands and government actors (as in the classical conception of Smith) but as elements that both shape and are shaped by processes, relationships, practices, and political representations that constitute public action. According to Freitas, “these processes reveal the subtleties of micropolitics, the interests of various actors in the constitution of artifacts that often establish strategic guidelines for the construction of public policies” (Freitas, 2016, p. 121).

Thoenig defines public action as “the way a society constructs and qualifies collective problems and elaborates responses, content, and processes to address them” (THOENIG, 1997, p. 28). This perspective challenges the conventional view of the political arena, which sees it as exclusively populated by governmental actors adhering to well-defined and straightforward protocols for their actions. Instruments of public action (public policies, laws, norms, etc.) are constructed by the collective actors who shape practices in the public sphere, composed of various actors, human and non-human, governmental and non-governmental. This theoretical perspective is applied here to understand democratic innovations as a constitutive element of public action.

This shift in focus, combining the concept of democratic innovation with the critical perspective of the field of public policy, breaks away from linear analyses that divide innovations into stages of a supposed policy cycle, as the traditional and positivist school of the field suggests. The view of each innovation becomes multidimensional, given the complexity and heterogeneity of governmental and non-governmental actors involved. Furthermore, the multiplicity of objectives and meanings of democratic innovations is observed. An initiative can be developed with the aim of contributing to the formulation of public policies and, at the same time, have characteristics and means of action that exert strong influence at other stages, such as in the evaluation and monitoring process, impacting and producing results.

Therefore, there is no linearity and no possibility of assigning to an innovation only one facet of the process of constructing such instruments because it happens through dialogical communication between actors from diverse sectors, filled with conflicts, contradictions, and interposed times. This perspective leads us to what Carvalho considers “a new representation of the notion of the public, which does not refer to sovereign power but to a space of controversies about public problems and their resolution methods” (CARVALHO, 2015, p. 317). This theoretical-methodological position also aligns with Duran’s definition of public policy proposed in the 1990s as “(…) a social process that unfolds over a specific period, within an institutional framework that constrains the type and level of resources available through interpretative schemes and value choices that define the nature of public problems presented and the direction of action” (DURAN, 1990, p. 240).

Politics and the Digital Landscape in Latin America between 1990 and 2020

Between 1990 and 2020, Latin America experienced different political moments that aligned with similar contexts in other parts of the world. The bipolar world characterized by the Cold War had given way to a world predominantly marked by capitalism. At the same time, democratically elected governments were replacing autocracies in the region, and a process of market liberalization and deregulation was beginning, commonly referred to as neoliberalism. Examples such as Fernando Collor and Fernando Henrique Cardoso in Brazil, Carlos Menem in Argentina, Alberto Fujimori in Peru, Goni (Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada) in Bolivia, Rafael Caldera in Venezuela, among others, marked the 1990s for prioritizing the privatization of public assets and economic liberalization.

However, there were latent forces in those countries that seemingly gestated a countermovement to neoliberalism that would emerge in the late 1990s. Initiatives rooted in trade union coordination, popular organization, student groups, and the peasant movement were experimenting with ways to build counterpowers to expand participation in the fragile nascent democracies. Intense battles of narratives and practices were developed to establish democracy.

Over the last 30 years, many Latin American countries have experienced a pendulum movement across the political spectrum. The first wave after authoritarian regimes in the 1990s was characterized by right-leaning governments. In the early 2000s, the pendulum swung towards the election of left-leaning governments (LIMA; COUTINHO, 2007). In the mid-2010s, the pendulum swung back towards the right side of the political spectrum, with the rise of conservatism and neoconservatism throughout Latin America (CRUZ; KAYSEL; CODAS, 2015; PINHEIRO-MACHADO, 2019; BIROLI; MACHADO; VAGGIONE, 2020; PEREIRA, 2020).

The fluctuation across different political spectrums in Latin America is also a result of movements within those societies. In Brazil, for example, participatory governance practices and the strengthening of popular organization in the 1980s and 1990s served as a guideline for values that propelled the Workers’ Party to power in the early 21st century. Alongside practices like Participatory Budgeting, public consultations, and sectoral policy conferences, considered democratic innovations according to the theoretical framework presented here, there was a democratic culture of inclusion and social justice.

The database subject of this analysis shows that the political values present in Latin American movements coincide with the different types of democratic innovations created in each of these periods. We observe significant changes in the political landscape that result in transformations in digital governance practices and norms, a context that encompasses and explains digital democratic innovations and their characteristics. These changes can be understood, especially in Brazil, through three distinct historical periods related to federal government practices associated with the use of digital resources and the implementation of democratic innovations.

The first period concerns the early use of the internet by the Brazilian federal government. Starting in the early 1990s, the Brazilian federal government, with the Bresser plan for the restructuring of Public Administration, developed guidelines for implementing what they called “e-government,” also introducing the concept of innovation applied to the public sector in the country. The term “e-government” was the first to be used to define the government context marked by the beginning of digital practices and interoperable systems. During this period, the idea of the state as a provider of services to citizens was widely disseminated, which was one of the central characteristics of the paradigm of managerial public administration. Digital practices emerged as suitable tools to increase efficiency in service delivery and public administration.

From 2003 onwards, the regulations and practices associated with e-government – based on the perception of the indispensability of automating services and technologies related to government practices – were combined with the reflection on the internet as an instrument of social and political transformation. In this period, at the beginning of the Workers’ Party’s government in Brazil, the instruments of public action formed a new context formally denominated “digital governance.” This new historical period emphasized the use of information and communication technologies for practices, mechanisms, and strategies aimed at inclusion through citizen political participation. One of the slogans for the construction of public policies, in fact, was “participation as a method of government”.

In this period of digital governance, there was an exponential increase in the number of digital democratic innovations focused on political inclusion, transparency and accountability. Among the initiatives aimed at political inclusion, there were a total of 10 initiatives until 2003. After that year, an additional 196 initiatives were created. Regarding initiatives focused on transparency and accountability, there were only 5 before 2003, but after that year, 525 initiatives were created (LATINNO, 2021).

Although the formal document defining the “Digital Governance Policy” was only published in 2016, it guided practices throughout the entire period of digital governance since 2003. The primary objectives of this policy were to (a) enhance information availability and the delivery of public services; (b) promote public participation in decision-making processes; and (c) elevate levels of accountability, transparency, and government efficiency (BRASIL, 2016).

This policy framework aimed to leverage digital technologies to enhance government services, engage citizens in decision-making processes, and improve the overall efficiency and transparency of government operations. These objectives align with the broader goals of digital governance and the use of technology to promote democratic participation and accountability in public administration.

During this period, democratic innovations flourished for various purposes, offering citizens the opportunity to directly and collectively create laws and public policies (as seen in platforms like e-Cidadania³ and e-Democracia4). Other initiatives offer citizens the chance to file complaints about inadequate public services or to collectively hold public officials accountable through initiatives promoting public transparency, such as the School of Open Data, Serenata de Amor5 and others focused on government accountability (NN, 2021).

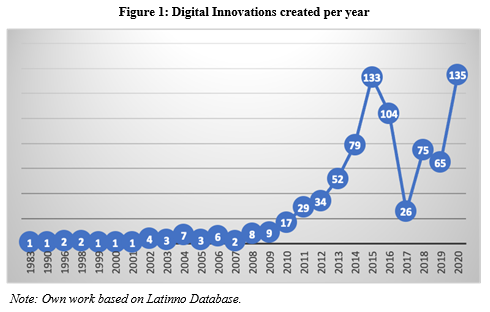

Until 2015, there was a notable expansion in the diversity of democratic innovations, encompassing a wide spectrum of values and involving a multitude of actors. After a significant growth in the number of digital democratic innovations created in the region, there was a slowdown in the emergence of initiatives from 2016 onwards, as indicated by graph 1. The late 2010s were marked by the rise of new conservative governments with political demands related to social values and the fight against corruption (CRUZ; KAYSEL; CODAS, 2015).

In Latin America, the rise of conservative political groups was accompanied by episodes of impeachment, such as the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in Brazil and the coup in Bolivia that ousted President Evo Morales in 2019. From an electoral perspective, several Latin American countries elected right-wing or far-right governments, which had direct implications for the formation of democratic innovations and the types of actors promoting them6.

In Brazil, after the 2018 elections, there was a profound transformation in the perception of citizen political participation in the federal government, and a new term began to be used consistently in decrees, strategies, and other government instruments. “Digital governance,” terms that had been adopted for over a decade, was renamed, and federal government practices were now part of what has been called the “digital government.” Significant changes were based on this seemingly simple change of terms (NN, 2021).

Digital participation was no longer encouraged and systematically discouraged and legally constrained. An example of this was Decree 9759, issued on April 11, 2019, which abolished or limited the activities of federal government committees. Additionally, Decree 8.243, issued on May 23, 2014, which regulated the National Policy for Social Participation (PNPS) and the National System for Social Participation (SNPS), was repealed. The PNPS and SNPS represented the recognition of dialogue between civil society and the government as they established parameters for organizing society and recognized the voice of these organizations in supporting public decision-making.

During this period (2019-2022), there were various attempts to institutionalize restrictions on spaces for democratic dialogue, such as public audiences, councils, and forums. The policy of digital government, in this case, was not left unscathed. It can be observed historically that there was a noticeable erasure of political and normative mechanisms related to citizen political participation and inclusion. At the same time, it can also be observed the continuity of digital governance policies – technical strategies that had been developed since the year 2000. We can observe this shift primarily in two key documents for digital government policy: Decree 10,332, issued on April 28, 20207, which established the Digital Government Strategy, and Law 14,129, issued on March 29, 20218, which establishes principles, rules, and instruments for Digital Government and the enhancement of public efficiency. The instruments that were previously emphasized for citizen participation, according to the Strategy, would be restricted to topics related to public transparency.

As participation lost its centrality in government actions and public action instruments, there was also a reduction in the number of digital democratic innovations starting in 2016 in Brazil and throughout other Latin American and Caribbean countries. The total number of initiatives discontinued after 20169 was more than double (84) the total number of initiatives closed up to that year (39). Another relevant data point is that the average age of initiatives discontinued after 2016 is almost double (2.8 years) the average age of initiatives closed before that year (1.5 years).

This data is revealing because it indicates that relatively established initiatives, with an average lifespan of almost 3 years, were closed after 2016. Furthermore, in 2020, there were the discontinuity of other initiatives with even longer lifespans, with twelve of them existing for about 4 years. According to the analyzed database, the years 2016 and 2019 recorded record numbers of closed initiatives (a total of 42). However, during the pandemic period, there was a reversal of this decline, at least for a certain period. According to Pogrebinschi, “this trend is similar for most countries, with some exceptions, such as Peru and Venezuela, which did not witness such clear increases or decreases in democratic innovations” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 20).

Based on the analyzed data, it can be observed how the political oscillations in Latin America contributed to the disappearance or flourishing of digital democratic innovations associated with the openness – or lack thereof – of governments to promote democratic policies aligned with different perspectives of digital governance. The next section will further analyze the Latinno’s database.

Democratic Digital Innovations After the Political Turn in Latin America

Brazil and other countries in Latin America went through processes of democratization after authoritarian regimes, which included encouraging citizen political participation through democratic innovations, whether digital or not (AVRITZER; NAVARRO, 2003; NN, 2020). Throughout the period during which the mapping of democratic innovations in Latin America and the Caribbean was conducted, the countries identified with the highest number of initiatives were Brazil, with 410, Argentina, with 387, and Colombia, with 351 (LATINNO, 2022).

In addition to observing governmental and political changes over these three decades, patterns of the relationship between the state and civil society were also observed. In Brazil, especially, civil society has a strong relationship of dependence on the state, a relationship that reverts to historical patterns considered authoritarian and centralized (DA SILVA, 2015).

Although the incorporation of participatory mechanisms in Brazil after the civil-military dictatorship fostered new practices and relationships between representatives and the represented, these were not sufficient to overcome those historical patterns (Ibid, p. 2). Participatory management mechanisms, in this sense, served to incorporate new forms of relationship between the state and society. Since until then, public policy management had “a significant relationship with the predominance of private, corporate, and electoral interests over the public interest” (Ibid, p. 2). In 2020, despite the apparent fatigue of utilizing digital political participation practices for citizen engagement, especially since 2016, there was a surge in digital democratic innovations driven by the pandemic. According to the research database, “in 2020, 128 democratic innovations were specifically conceived to address problems resulting from the pandemic. This number is almost as high as the average annual creation of democratic innovations in the region in the three previous years” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 24).

It is noteworthy, therefore, the significant growth in the emergence of digital democratic innovations in the first year of the new coronavirus pandemic (2020), and especially the fact that initiatives for political inclusion and social control have overshadowed accountability and responsiveness initiatives. Apparently, civil society responded to the authoritarian threat driven by the pandemic by creating its own processes to address this phenomenon through citizen engagement, primarily through support networks. This argument becomes even stronger when we analyze who developed these new initiatives, as will be discussed below.

Multiple Actors creating Digital Democratic Innovations

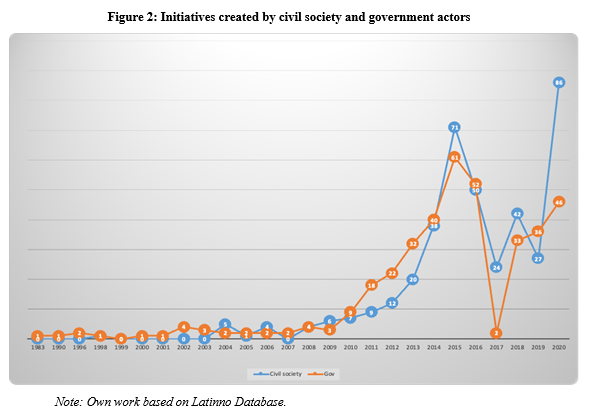

While there has been noticed a decline in the number of digital democratic innovations funded by government actors, there has also been a substantial increase in the number of initiatives developed by non-governmental actors such as collectives, civil society, and businesses10. The following graph 2 illustrates the evolution of initiatives created by civil society actors compared to initiatives driven by governments. There is a coherence between the two sectors over the years, except for 2020 when civil society was responsible for almost twice the number of digital democratic innovations created.

It is interesting to note that one of the periods with the highest number of initiatives implemented by civil society coincides with many initiatives being terminated. Furthermore, after the year 2019, which had the highest number of initiatives discontinued over the course of the 30 years analyzed, 2020 is the year with the highest number of civil society initiatives implemented. This reveals the strength of non-governmental organizations in combating the pandemic and strengthening participatory democratic practices. According to the final report of the research database,

In the first 100 days of the pandemic (between March 16 and July 1, 2020), 309 other civil society initiatives were created with the specific goal of mitigating the impact of the Covid-19 crisis. These initiatives involved at least 688 organizations (including civil society organizations, universities, professional associations, and citizen collectives, among others) across the region (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 24).

The increase in the number of democratic innovations developed and implemented by civil society can also be seen as an indirect effect of the democratization process experienced by Latin American countries. As we shall see further on, these effects do not hold a strong connection with democratic values and therefore do not mean necessarily democratic gain. Even though citizens are engaged in participatory mechanisms, that does not mean necessarily overcoming the liberal democracy and representativeness crisis in the region.

There has been a growth of non-institutionalized horizontal networks and organizations. They are often built in emergency scenarios, such as the context of the pandemic, in a multisectoral and multi-actorial way. Hundreds of support networks for specific communities were created to fill the void left by governments – subnational and national – in relation to specific pandemic-related programs, policies, and government actions in countries of the region, especially Brazil and Argentina. New survival strategies were created independently of government support. This phenomenon became apparent with the significant rise in the number of democratic innovations in 2020, primarily implemented by actors from civil society.

In 2020, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 54% of the democratic innovations created were introduced by civil society organizations, 85% of which had no government involvement. According to the research database final report, “the number of democratic innovations created by civil society in 2020 is 62% higher than it was in 2010” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021: 23). The strong trend of civil society taking the lead in creating democratic innovations, especially from 2020 onwards, suggests that as the pandemic led to a certain absence of governments, civil society responded by creating new spaces for exposing claims and demands through digital political participation.

The scenario of multiple actors in the formulation and implementation of digital democratic innovations becomes evident. Up to 2018, there were 58 initiatives that had partnerships with companies; in the short period between 2019 and 2021, 55 new initiatives of this type emerged, which is more than 10% of the total number of initiatives analyzed in the region, indicating a significant increase in this form of association among networks of multiple and diverse actors. From the total of 1,055 digital democratic innovations, 113 of them were created through partnerships with companies.

Formalization and Continuity of Democratic Innovations

One of the central concerns of the public action perspective is the continuity and sustainability of digital democratic innovations. The discontinuity of many initiatives can be explained, among other factors, by their lack of formalization and the disincentive for their permanence, as seen in Latin America, especially from 2016 onwards. In this regard, the development and implementation of public action instruments that strengthen these initiatives, such as laws and public policies, tend to ensure their continuity and consolidation. The research database presented here reinforces this observation by stating that “the durability and impact of democratic innovations in Latin America are severely compromised by their lack of institutionalization and their low capacity to produce binding decisions” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 25).

When specifically analyzing digital democratic innovations, the results are quite similar. A recent study analyzed 526 digital democratic innovations in Latin America and the Caribbean and found that initiatives with political or legal support tend to produce more outputs and effective results (Freitas, 2020; Freitas; Sampaio; Avelino, 2023). The percentage of effective outcomes from initiatives without institutional or legal support is much lower than that related to innovations with some form of legal or political provision.

The research carried out with the 526 digital democratic innovations concluded that only 13% of innovations without formalization generated outcomes. On the other hand, for innovations backed by legal support, the rate of successful outcomes reached 35% (Freitas, 2020). From the total, 33% of innovations with political and/or governmental support generated effective results, and many of them constituted instruments of public action. These instruments enabled by digital democratic innovations represent direct effects for the target audience and also offer more conditions for the sustainability of these initiatives over time.

Scenario and Tendencies

It is interesting to note that many advances achieved during three decades of digital governance in the region has been maintained, albeit without a central focus on citizen political participation. As observed by Freitas; Sampaio; Avelino, 2023) the process of democratization in latin american countries has implications that go beyond practical effects. This period has engendered new forms of citizenship and new perceptions of the individual as a citizen, a rights-holder, and an active voice. These are implications that may not be easily measurable or identifiable objectively. The acquired rights tend to be visibly cumulative (Gohn, 2019).

However, it is worth noting that such indirect implications may not necessarily represent a democratic gain. Citizen empowerment and awareness of their rights generate greater political articulation capacity. This capacity, closely associated with citizen participation, can be exercised with various objectives that are not necessarily tied to the realization of democratic ideals, such as political and social equality. Discursive practices on social media are examples of political expression that are often more associated with a possible rise of neoconservatism values than with mechanisms of democratic strengthening in terms of respect for others and the pursuit of social equality (BIROLLI; MACHADO; VAGGIONE, 2020).

The more active participation of non-governmental actor networks in the construction of democratic innovations does not necessarily mean a democratic gain, even though it can be understood as part of the implications of the democratization process. As Mendonça and Domingues point out, several authors in the field suggest “caution regarding the direct connection between civil society and democracy” (Mendonça; Domingues, 2021). It is necessary to reflect on numerous other factors that interfere with their functioning and dynamics associated with their constitution, such as the type and quality of decisions, purposes, and the source of resources responsible for their maintenance. According to the authors, “such studies reveal that the promotion of engagement is not, in itself, synonymous with democratic strengthening” (Mendonça; Domingues, 2021, p. 4).

Another factor that explain the current scenario is the strengthening of an “anti-representation individualism” (MENDONÇA; DOMINGUES, 2021, p. 2). A trend towards a decrease in the quantity of these initiatives from 2016 may reveal a weariness of participatory practices justified by both political factors at the time and also by a voluntary distancing of individuals from centers of power and decision-making processes. Citizen participation ranges from massive demonstrations to more distant practices, such as social media posts criticizing established power and its representatives, but without the overt intention of interfering in decision-making processes.

Mendonça and Domingues suggest three other dynamics that may have contributed to a weakening of democracy in different contexts: “a focus on the national level; an opening for the reappearance of authoritarian forces contained within society, and polarization that increases the cost of tolerance” (MENDONÇA; DOMINGUES, 2021, p. 36). The historical path of digital democratic innovations follows this trend. Combina-se a isso o fato de que existem mais inovações democráticas com o objetivo de criar mecanismos para aprimorar a prestação de contas públicas, accountability e responsividade do que inovações voltadas à equidade e justiça social.

Furthermore, various digital resources are not only being used to strengthen democracy. A significant portion of them is intended for the dissemination of false information, the formation of opinions based on misinformation, in uncontrollable, unknown, and difficult-to-access networks. With the COVID-19 pandemic, various digital resources began to be used to combat it, while fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy and personal data protection, are increasingly being violated by applications and other technological artifacts primarily aimed at controlling the pandemic (Freitas; Capiberibe; Montenegro, 2020).

The fact that participation through digital means is present in political mobilization processes draws attention to the sociotechnical nature of digital democratic innovations. Digital resources used are becoming increasingly fundamental to political processes. However, the countless ways in which information can be manipulated through the use of these same digital resources reveal the possibility of scenarios unfavorable to democracy.

Conclusion

This article analyzed the historical trajectory of digital democratic innovations in Latin America and the Caribbean over 30 years of existence (1990-2020). Concepts from the theory of public action were employed to understand the data collected by the Latinno Project, discussing historical and contextual elements regarding the different periods of creation and implementation of digital democratic innovations. An analysis based on legal aspects and governance mediated by digital resources was also conducted, taking as a reference the transformations in Brazil in this scenario. The article reveals that digital democratic innovations in Latin America continue to flourish, even in a context shaped by conservative governments. The sustainability of this scenario, however, depends on strategic planning and political actors committed to strengthening democracy in the region.

The different political moments in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1990 and 2020 allow for an analysis of the panorama of values, norms, and practices that guided the countries in different historical periods. Different government political spectrums influenced the emergence or termination of democratic innovations. Even with the rise of far-right governments, democratic innovations continued to thrive. Until the 2010s, governments further to the left of the political spectrum were the promoters of democratic innovations. However, in the last decade, civil society has played a predominant role as the creator of new initiatives. Governments still create initiatives, but they are no longer their main drivers.

Participatory democracy is alive in the hands of civil society. It is worth noting the significant increase in initiatives during the first year of the pandemic, especially participatory management initiatives mobilized by civil society, demonstrating the vigor of non-governmental actors in proposing solutions to public problems through democratic participation mechanisms. However, this data does not necessarily imply enduring democratic gains, as the institutionalization of these initiatives also requires greater openness from the state to accommodate the formulations and demands produced by these initiatives.

The challenge now is to develop strategies for the institutionalization and formalization of these initiatives, creating societal interfaces to influence public decisions. Therefore, analyzing the democratic implications of this scenario leads to the perception of the need for future studies that qualitatively analyze the micropractices of governance. By analyzing these practices in more depth, one can better understand the multiple actors who collaborate in the process of developing sociotechnical artifacts that participate in the elaboration and implementation of policies and other elements that constitute public action.

The theoretical perspective adopted here has significant explanatory power in this scenario, as it broadens the analytical framework to include various and multiple elements to explain the process of constructing public action, including the great diversity of actors who act together and interdependently. This issue related to actor heterogeneity is a sensitive matter for the perspective of public action theory because it not only recognizes the greater variety of actors involved but also makes present the diversity that inhabits each of the social and political networks involved. It takes into account the plural, composite, and occasionally conflictual nature of the state – composed of groups of interest with multiple and diverse interests and objectives.

Captions of the figures:

Figure 1: Digital Democratic Innovations created per year

Note: own work based on Latinno Database.

Figure 2: Initiatives created by civil society and government actors

Note: own work based on Latinno Database

¹ A year before Graham’s book was published, Leonardo Avritzer and the participatory studies school at the Federal University of Minas Gerais had coined a concept similar to Smith’s, that of Participatory Institutions. Broadly speaking, Avritzer defined Participatory Institutions (PIs) as different forms of incorporating citizens and civil society associations into policy deliberation (AVRITZER, 2009). Through the refinement of the concept in subsequent works, it can be stated that PIs are institutional forms mediating the relationship between the political system, parties, state agents, and civil society, articulating forms of representation and participation to establish power-sharing arrangements (AVRITZER, 2008, 2009).

² Database available at the project´s site: https://www.latinno.net/pt/.

³ https://www12.senado.leg.br/ecidadania

4 https://tes.edemocracia.camara.leg.br/

5 https://serenata.ai/

6 According to Pogrebinschi, “democratic innovation in Latin America has always been characteristically led by the state. Since 1990, governments have been involved in a total of 68% of the institutions, processes, and mechanisms created to enhance democracy through citizen participation. However, starting in 2016, this pattern reversed, and the role of governments in democratic innovation decreased across the region. This was particularly abrupt in some countries, such as Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Uruguay” (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 20).

7 available at <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2019-2022/2020/Decreto/D10332.htm>. Acesso em 30 de mar 2022.

8 available at <https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/lei-n-14.129-de-29-de-marco-de-2021-311282132>. Acesso em 30 de mar 2022.

9 The database was updated until December 2020.

10 According to the research database, 85% of the democratic innovations addressing issues resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic made use of digital participation (POGREBINSCHI, 2021, p. 24).

Bibliographic References

Araújo, M. S. S., & Carvalho, A. M. P. 2021. “Autoritarismo no Brasil do presente: bolsonarismo nos circuitos do ultraliberalismo, militarismo e reacionarismo.” Revista Katálysis 24: 146-156.

Avritzer, L., & Navarro, Z. 2003. A inovação democrática no Brasil. São Paulo: Ed. Cortez.

Avritzer, L. 2008. “Instituições participativas e desenho institucional: algumas considerações sobre a variação da participação no Brasil democrático.” Opinião pública 14: 43-64.

Avritzer, L. 2009. Participatory institutions in democratic Brazil. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Barber, B. 2003. Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. Univ of California Press.

Biroli, F., Machado, M. D., & Vaggione, J. M. 2020. Gênero, Neoconservadorismo e Democracia: disputas e retrocessos na América Latina. São Paulo: Boitempo.

Brasil. 2016. Decreto no. 8.638, de 15 de janeiro de 2016. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/decreto/d8638.htm. Accessed March 30, 2022.

Carvalho, L. M. 2015. “As políticas públicas de educação sob o prisma da ação pública: esboço de uma perspetiva de análise e inventário de estudos.” Currículo sem Fronteiras 15(2): 314-333.

Cruz, Kaysel, & Codas. 2015. Direita, volver! O retorno da direita e o ciclo político brasileiro. São Paulo: Perseu Abramo.

Da Silva, R. M. A. 2015. “Desafios da democracia participativa: padrões de relação Estado e Sociedade no Brasil.”

De Oliveira Nunes, E. 1997. A gramática política do Brasil: clientelismo e insulamento burocrático. Zahar.

Duran, P. 1990. “Le savant et le politique: pour une approche raisonnée de l’analyse des politiques publiques.” L’Année Sociologique 41: 227-259.

Freitas, C. S. 2016. “MECANISMOS DE DOMINAÇÃO SIMBÓLICA NAS REDES DE PARTICIPAÇÃO POLÍTICA DIGITAL.” In Democracia Digital, Comunicação Política e Redes: Teoria e Prática, edited by Sivaldo Pereira da Silva, Rachel Callai Bragato, and Rafael Cardoso Sampaio. Rio de Janeiro: Letra & Imagem, Folio Digital, 1ª ed., 27-45.

Freitas, C. S. 2020. “IMPLICAÇÕES DA E-PARTICIPAÇÃO PARA A DEMOCRACIA NA AMÉRICA LATINA E CARIBE.” Revista Contracampo 39(2): 1-16.

Freitas, C. S., Capiberibe, C., & Montenegro, L. 2020. “GOVERNANÇA TECNOPOLÍTICA: BIOPODER E DEMOCRACIA EM TEMPOS DE PANDEMIA.” Nau – A Revista Eletrônica da Residência Social 11(20): 191-201.

Freitas, C. S. 2021. “INOVAÇÕES DEMOCRÁTICAS DIGITAIS PARA TRANSPARÊNCIA GOVERNAMENTAL NA AMÉRICA LATINA E CARIBE: POSSIBILIDADES E DESAFIOS.” Comunicação & Inovação (Online) 22(48): 80-96.

Freitas, C. S., Sampaio, R., & Avelino, D. 2022. “PROPOSTA DE ANÁLISE TECNOPOLÍTICA DAS INOVAÇÕES DEMOCRÁTICAS.” Gigapp Estudios Working Papers.

Gohn, M. 2019. Participação e Democracia no Brasil. Petrópolis: Ed. Vozes.

Gomes, W. 2018. A democracia no mundo digital: História, problemas e temas. Edições Sesc.

Lascoumes, L., & Le Galès, L. 2012. “A ação pública abordada pelos seus instrumentos.” Revista Pós Ci. Soc. 9(18): jul/dez.

LATINNO. Projeto LATINNO 2021. Available at: https://www.latinno.net/. Accessed September 30, 2023.

Lima, M. R., & Coutinho, M. V. (Eds). 2007. Agenda sul-americana: mudanças e desafios no início do Século XXI. Brasília: Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão.

Mendonça, R. F., & Domingues, L. B. 2021. “Protestos contemporâneos e a crise da democracia.” Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política.

Pateman, C. 1992. Participação e teoria democrática. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

Pereira, P. (Ed.) 2020. Ascensão da nova direita e colapso da soberania política: transfigurações da política social. São Paulo: Ed. Cortez.

Pinheiro-Machado, R. 2019. Brasil em transe: Bolsonarismo, nova direita e desdemocratização. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Oficina Raquel.

Pogrebinschi, T. 2021. “Trinta Anos de Inovação Democrática na América Latina.” WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Berlin.

Sampaio, R. C. 2011. “Instituições participativas online: um estudo de caso do orçamento participativo digital.” Revista Política Hoje 20(1).

Santos, B. S. 2009. “Democratizar a democracia: os caminhos da democracia participativa.” In Democratizar a democracia: os caminhos da democracia participativa, edited by B. S. Santos.

Smith, G. 2009. Democratic innovations: Designing institutions for citizen participation. Cambridge University Press.

Thoenig, J. 1997. “Política pública y acción pública.” Gestión y Política Pública VI(1): 19-37.

¹Christiana Soares de Freitas

CV: http://lattes.cnpq.br/5250541522722172

She is currently Head of the Department of Public Policy Management at the Faculty of Economics, Business, Accounting Sciences and Public Policy Studies at the University of Brasilia (UnB). She is Associate Professor at the Graduate Program at the Faculty of Communication (FAC) and at the Graduate Program in Governance and Innovation in Public Policies (PPGIPP) at UnB. She is a founding member and researcher at the National Institute of Science and Technology in Digital Democracy (INCT.DD). She is a researcher at the Grupo de Investigación en Gobierno, Administración y Políticas Públicas (GIGAPP/Spain). She is the leader of the research group GERIS that focuses on studies regarding the State, Regulation, Internet and Society. She is a member of the Deliberative Council of the Open Knowledge Foundation Brazil and also a member of the Advisory Board of ANEPCP (National Association of Teaching and Research in the Public Field). She holds a postdoctoral degree in Public Policy Studies and Digital Governance from GovLab, New York University (2018). She holds a PhD in Sociology of Science and Technology from the University of Brasília and the Open University, England (2003). She has experience in the areas of Innovation in the Public Sector, Digital Democracy, Digital Rights, Digital Governance, Internet Regulation, Sociology of Science and Technology, Communication, Public Administration, Theory of Organizations and Public Policies. Her main research topics involve the analysis of networks for political participation; regulatory policies on the use of media and social networks; open networks for the production and dissemination of knowledge; knowledge commons as an engine of innovation and generation of public value; evaluation of government programs and public policies. Concepts addressed and developed in research and articles include digital political participation; knowledge commons; tecnologic innovation; digital governance; technological-informational capital; information and communication technologies; free software and public software; administration and evaluation of digital public services; democratization of knowledge in the network society and digital democracy.

²CV: http://lattes.cnpq.br/7243569051300788

Marco Konopacki, PhD, is the Director of Governance and Digital Innovation at the General Public Defense of Rio de Janeiro, where he is leading efforts to modernize the agency’s operations and improve access to justice for citizens. As a Fulbright Humphrey Fellow on Technology Policy and Management at Syracuse University, Marco developed expertise in the intersection of technology and public policy, which he now applies to his work in the public sector. He is a skilled programmer and has experience developing software solutions for various types of organizations. In his current role, Marco is focused on using technology to streamline operations, increase efficiency, and enhance the agency’s ability to deliver legal services to the public. He is passionate about using his skills to drive positive change and is committed to making a meaningful contribution to the field of governance and digital innovation.

³CV: http://lattes.cnpq.br/9474169488630049

Jean Campos. Journalist (UFMT), PhD student in Communication (UNB), Master in Law (CEUB), Specialist in Communication Management in Organizations (CEUB). He is currently coordinator of Communication and leader of the Production and Dissemination of Information in Science, Technology and Innovation project, at the Center for Management and Strategic Studies (CGEE). He was Secretary of Communication in the Government of Mato Grosso (2015-2016).