REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/fa10202503222138

Walter Camargos Junior1

ABSTRACT

Background: The phenomenon of transitioning away from a clinical diagnosis of Autistic Disorder has been recognized for decades, yet its relationship with sex/gender remains unclear.

Objective: To determine whether clinical outcomes of Autistic Disorder diagnoses are associated with sex/gender and age, and to evaluate any statistical differences between non-Autistic Disorder medical conditions and sex/gender.

Methods: Database study of the Child Development / Autism Spectrum Disorders Clinic of a tertiary pediatric hospital and non-public origin, with entry up to 48 months of age, between August 2009 and June 2020. The clinical diagnosis used DSM-IV 299.00 and was established from 36 months onwards. The medical diagnosis and the non-Autistic Disorder medical disorders that could potentially cause developmental delays were exclusion criteria for the study and were monitored.

Results: Among 906 children, 186 were excluded, and 68 transitioned out of the Autistic Disorder clinical diagnosis. Transitioning out was not statistically associated with sex/gender but was significantly related to the number of consultations and age. No significant relationship was found between sex/gender and the presence of medical conditions.

Conclusions: Sex/gender is not associated with Autistic Disorder clinical diagnostic stability nor with the comorbidities found. However, age and consultation frequency significantly influence diagnostic outcomes, highlighting the importance of longitudinal clinical evaluations.

Keywords: Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, sex/gender, diagnostic, outcome

INTROUCTION

The Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurobiological disorder that affects the areas of interaction, social communication and specific behavior patterns. Its symptoms manifest early in childhood, with boys being affected more frequently than girls, at an average ratio of 4:1. In the United States, the prevalence is estimated at 1:54 among children up to eight years old [1].

The clinical criterion for the diagnosis of Autistic Disorder (AD) – 299.00 was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – IV (DSM-IV), noted for its technical quality and stability over time [2,3], but not at ages below 36 months [4]. Ozonoff et al. [5] report that the diagnosis depends on age, with some children being diagnosed only at 36 months, not being identified in previous evaluations.

The comparison of the technical quality of the DSM-IV with tests such as the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale, is favorable to it as a diagnostic instrument [4,6,7], as it utilizes an extensive amount of information from the family and the child during the consultation, along with the professional’s experience [4]. Other authors [8,9] suggest that the “gold standard” for the diagnosis quality is the clinical judgment of experienced professionals. It is important to note that in Brazil, several diagnostic tests are not approved for clinical use by the Federal Council of Psychology.

Setting the diagnosis age at 36 months provide a robust safety range [2,5,10], with clinical evaluations indicating greater diagnostic stability for Autistic Disorder starting at age three.

Several published articles discuss the progression of the DSM-IV diagnoses [2,4,11-18], including the possibility of transitioning away from them. The oldest article, by Rutter et al. 1967[19], reports that 9/63 (14%) ‘could no longer be classified by the term Autistic’ during follow-up assessments. These studies also emphasize the importance of comparative research between sexes/genders. None of the cited articles [2,4,11-19], had as their primary objective the differentiation of evolution based on sex/gender. Additionally, the vast majority of articles also do not individually report results for the diagnosis of AD (Autistic Disorder), and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), which are more likely to transition away from the diagnosis [13,15,15,20].

Diagnostic mobility is multi-directional, involving transitions such as migration from AD to PDD-NOS, from PDD-NOS to AD, and from both (AD and PDD-NOS) to transitioning away from the diagnosis [4,13,14,18,20], including relapse [5], and transitioning to nonASD diagnoses like Other Developmental Disorders and Reading Disorders [4]. Reports indicate a higher percentage of transitions from PDD-NOS diagnoses than from AD ones [2,4,13-16]. Few authors [11,13,15] report results specifically related to sex/gender, and several studies suggest that girls experience more severe conditions with a worse evolution [21,22]. There are questions about whether this severity is due to Intellectual Disability (ID) [23-26] and the lack of identification (diagnosis), leading to the assumption that AD itself is more severe in girls [27].

The girls with autism are also reported to have higher rates of epilepsy, strongly associated with ID [28,29], independent of the presence of ASD [29]. Additionally, the female population is more likely to experience new mutations [30], which are known to be one of the causes of ID [31].

The term “sex/gender” is used here to acknowledge that the effects of biological “sex” and socially constructed “gender” cannot be easily separated, and that most individuals’ identities are shaped by both.

The primary objective of the study is to identify whether there is a correlation between transitioning away from the clinical diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, as per DSM-IV, and sex/gender.

The secondary objectives are: to determine if there is a difference in transitioning away from the clinical diagnosis of AD in relation to the number of consultations/age, to evaluate whether there is a statistical difference among sex/gender regarding the presence of Other Developmental Disorders, non-AD.

METHODS

This retrospective study analyzed the medical records of children treated at the Infant Development Ambulatory / Autism Spectrum Disorders clinic of a tertiary public pediatric hospital (Hospital Infantil João Paulo II, FHEMIG) and at the author’s private practice from November 2009 to June 2020. At both locations, only psychiatric medical care was provided, with other treatments left to the families’ discretion, and not under the study’s control.

The diagnosis of AD was clinical, based on DSM-IV criteria which served as both an “entry” criterion (from 36 months of age) and an outcome criterion for transitioning away from the diagnosis. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers was used as a screening tool from 24 months of age while awaiting the definitive diagnostic age.

The data were grouped according to the number of consultations, ranging from the first to the maximum number attended by each patient. Exclusions included cases of clinical diagnosis “entry” and transitioning away from AD, as well as abandonment of follow-up at the Ambulatory at any point during the study period.

Patients who presented any other base/primary condition that, by itself, caused delays in child development of any kind, were excluded. There were suspicions of non-AD clinical conditions that were referred to other specialists and did not return, which is why they were excluded from the “No diagnosis” classification.

No active follow-up was conducted for patients who missed scheduled appointments, and absenteeism was not controlled.

Inclusion criteria:

· Children suspected of having AD diagnosis during the first consultation, up to 48 months of age;

· Children diagnosed with AD by DSM-IV criteria from 36 months of age by a senior child psychiatrist qualified for the task;

Exclusion criteria:

· Children with a history of confirmed underlying/primary diagnosis during the follow up of any disorder or syndromes causing development delays;

· Children with a history of birth before 32 weeks of gestation, birth weight below 1.5 kg, Apgar scores below 4 at the 5th or 10th minute, morbid events that occurred up to the complete end of the seventh day of life, chromosomal abnormalities in general, genetic diseases, epilepsy difficult to control by the 2nd year of life, Cerebral Palsy, deafness, blindness, Profound Intellectual Disability, so on;

· Children with clinical conditions lacking a precise differential diagnosis for another medical disorder causing development delays;

· Children diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder (BD) and Psychotic Disorder (PD) during follow-up.

Statistical Analysis:

The Chi-Square test and The Fisher’s Exact test were used. The Fisher’s Exact test provides an alternative approach to the Chi-Square test when its conditions of applicability are not met, such as in small samples or when some cells in the contingency table have very low frequencies, to compare the occurrence of comorbidities between sexes.

To compare the outcome of the diagnosis within the variables of interest, two approaches were applied: the first consisted of using Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact tests for categorical variables. For numerical variables, the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare means or medians between groups. This non-parametric test is suitable for small samples or data distribution that deviate from normality.

The Kaplan–Meier estimator was used to analyze the time until the occurrence of the diagnosis outcome, [32]. The analyses were performed in the R, version 4.3.1. The level of statistical significance adopted was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

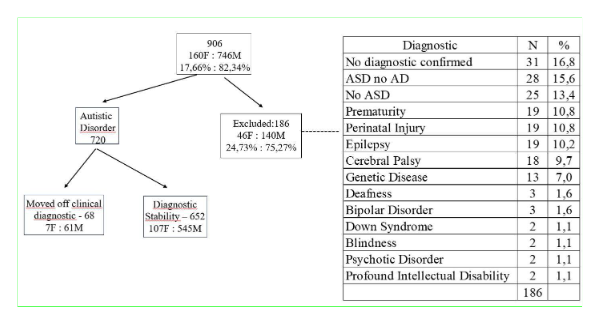

During the period from November 1999 to June 2020, 906 medical records of patients admitted to the Infant Development Ambulatory up to 48 months of age were analyzed. Among these, 82.34% were male, 7.51% transitioned away from the clinical diagnosis at some point up to the 21st consultation, and 20.52% had a medical disorder other than AD that could potentially cause developmental delays (Table 1).

Table 1 – Description of categorical variables.

*TA: Autistic Disorder (DSM-IV: 299.00); **ASD: Autistic Spectrum Disorder; Prematurity: below 32 weeks of pregnancy ***Other Disorders: Diagnosis / Diagnostic Hypothesis of other underlying disorders that cause delays in child development but are not clarified during follow-up.

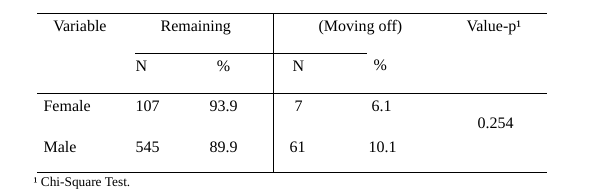

Table 2 – Comparison of Categorical Variables Between Remaining or Moving off

From the Diagnosis by Sex/Gender

Fifty percent of patients attended only one consultation, and 25% had at least three consultations.

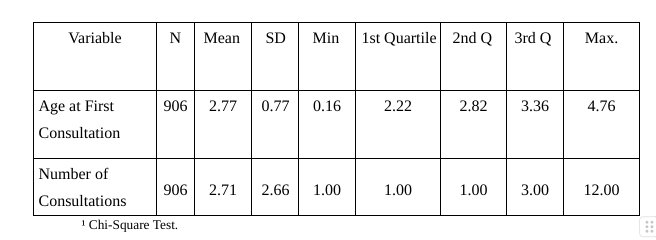

The Table 3 shows that at least 50% of the patients were the minimum of 2.82 years old at their first consultation, with an average age of 2.77 years and a standard deviation of 0.77.

Table 3 – Descriptive Statistics of Numerical Variables.

Nearly half of the children (33 out of 68) moved off the diagnosis by the 3rd consultation, with an average age of 52 months, and the vast majority (59 out of 68 – 86.8%) transitioned by the 6th consultation, at an average of 55 months. Three children moved off the diagnosis at the 7th consultation, two at both the 8th and 9th consultations, and only one at the 10th and 11th consultations.

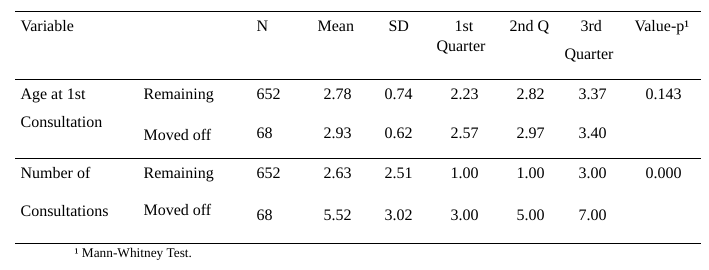

Table 4 shows that there was no significant difference in the age at the first consultation between those who moved off and those who remained in the diagnosis. However, there was a significant difference in the number of consultations and the moving off from the diagnosis. Patients who moved off had a higher number of consultations and were consequently older.

Table 4 – Comparison of Numerical Variables between Remaining or Moving off the Diagnosis

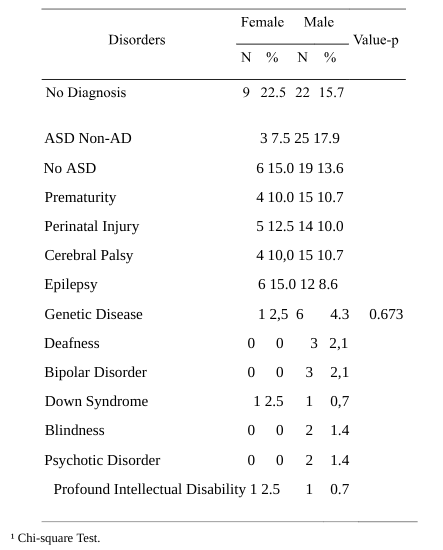

The statistical study on Other Diagnoses in general – the excluded ones, shows a significant difference (p-Value > 0.006) of higher presence in the female sex/gender. With the aim of understanding this result, a case-by-case analysis was conducted and it was found that in the group of genetic diseases, there was a high number (6 out of 50, or 12.0%) of girls diagnosed with Rett Syndrome / “Rett-like”, which was identified as a bias and removed from the calculation.

This new statistical study showed no statistical differences (p-Value = 0.673) – Table 5.

Table 5 – Comparison of Other Disorders between genders/sexes, excluding S. Rett / “Rett-like”.

Genetic Disease in girls: 6 with Rett Syndrome / “Rett-like”, 1 with Inborn Errors of Metabolism. Genetic Disease in boys: 1 with Williams Syndrome / Tuberous Sclerosis / Achondroplasia / Fragile X Syndrome, 2 with Inborn Errors of Metabolism.

DISCUSSION

Some results were consistent with the literature, such as a predominance of males (82.34%) in the sample; a high frequency of environmental disorders [33], like Prematurity (10.8%), Perinatal Disorders (10.8%), and Cerebral Palsy (9.7%) 34,35], which are potentially preventable through improvements in socioeconomic status and prenatal medical care.

The outcome from the diagnosis depended on the number of consultations – Table 4, as previously described [5]. The vast majority of children (59/68) moved off by the 6th consultation at 55 months consistent with Lord et al. [2] who stated that ‘the classifications changed substantially more often from ages 2 to 5 years than from ages 5 to 9 years’, and with the results of studies that researched up to ages 42 months [12], 48 months [15], 54 months [14], 60 months [11], and 72 months [13]. This search found a median of 7.5% (68/720) moved off the AD diagnosis at some point, in line with articles that used the DSM-IV with results ranging from 1% to 31.5% (median 8%) – 1% [2], 3% [14,17], 6.5% [4], 8% [13], 9.3% [18], 12.5% [15], 15% [11] and 31.5% [16].

The study found no statistical difference in the outcome from the diagnosis concerning gender/sex (Table 2), using the basic DSM-IV criterion. Harstad et al [36], based on the DSM-5, without specifying severity levels, state that the female gender/sex is a positive predictive.

The possibility of moving off clinical diagnosis may provide new insights for a large number of medical and non-medical professionals, as well as for families. This information reduces the belief in the “extreme malignancy” of AD, generates more optimism in the therapeutic management of this population and their families, increases engagement in physician-patient/family relationships, and consequently enhances technical and human improvement.

The fact that half of the patients had only one consultation can be understood by the specific objective of obtaining a diagnosis, regardless of whether it was initiated by the family or a professional. The mean age at the first consultation was 33 months (Table 3), which may indicate a temporal delay in seeking and/or accessing specialized services when compared to the literature [37,38].

The study found that the median of 7.5% of people moved off the diagnosis, which was compatible with the literature data (8%) [2,4,11,13-18]. In literature, the researches were conducted in services where children received recommended therapies, but this study had no control over the quality or quantity of therapies, and the treatments varied widely in both quantity and quality as public and private services were used.

The initial study’s finding regarding the higher incidence of other non-AD disorders in females, which led to a reassessment, was influenced by the presence of six girls diagnosed with Rett Syndrome/”Rett-like” conditions, referred to the professional specifically due to their recognized knowledge in the subject by hospital professionals. Petriti et al. [39] report a prevalence of 1:14,219 girls, which means that for this result not to be a bias, the sample would need to include approximately 170,000 children.

Regarding primary non-AD medical disorders, excluded (Table 1), the doubt/lack of diagnosis had the highest frequency – 16.8% (31/186), which may mean that there is still much unclear information on this matter. This was followed by ASD non-AD (15.6%) and without ASD clinical conditions (13,4%) and by, with the first having a higher percentage incidence in males (17,9% versus 7.5%) (Table 6).

We can analyze the inter-groups data, where all disorders proportionally affected more boys, except Profound Intellectual Disability. When we compare intra-group (Table 6 – 40F: 14M), we find only one proportional discrepancy: non-AD ASD affecting 7.5% in girls and 17.9% in boys.

Patients with Bipolar Disorder and Psychotic Disorder, excluded for this reason, were all male, only the former moved off the diagnosis.

Further studies are needed to better clarify the addressed matter and to develop monitoring methodologies for outcomes and possible relapses [5] throughout life, as done by Margaret H. Sibley et al. [40] for ADHD.

The positive points are the long follow-up period, the significant sample size, the diagnosis made by a senior child psychiatrist based on recognized quality instruments such as the DSM-IV, and him being the first Brazilian study on the subject.

The weaknesses include the diagnosis made by only one professional, even if senior in the subject, and the lack of tests such as ADOS, which is only approved by the Brazilian Federal Council of Psychology for researches purposes. Additionally, there is a lack of data on functional levels, such as expressive and receptive language skills and intelligence.

The lack of diagnosis in 16,8% of the excluded cases (31/186), classified as non-diagnosis type, may have compromised a more accurate view of the reality of the excluded individuals. The lack of follow-up for all those entered into the database (absenteeism control) would have provided a more comprehensive reality.

CONCLUSION

The study demonstrates that the moved off from the Autism Spectrum Disorder diagnosis occurs equally in both sexes/genders and is more frequent up to the age of five.

There is no statistical relevance between gender/sex and other medical disorders (nonAD) affecting neurodevelopment. Non-AD ASD occurred in a significantly larger number of males (17.9%) versus females (7.5%).

The initial consultations occur late, that the high number of occurrences of only one consultation in specialized services (tertiary-level hospital) is insufficient. The high number of patients without a non-psychiatric diagnosis reflects the low capacity for resolution in the healthcare system. The high incidence of Prematurity/Perinatal Injury/Cerebral Palsy and Epilepsy (around 10% each) may indicate deficiencies in prenatal care and even during childbirth.

Abbreviations:

Autism Spectrum Disorder: ASD

Autistic Disorder: AD

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM

Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified: PDD-NOS

Intellectual Disability: ID

Bipolar Disorder: BD

Psychotic Disorder: PD

Ethical Aspects: The project was approved under CAAE register No.

49999521.1.0000.5119 (Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Consideration – CPEC),

Review No.: 4,861,990 – FHEMIG / Brazil, and no Consent Form was required as it is a

retrospective study.

Author’s Contribution: there´s only one author

Funding: No funding

Data Availability Statement: The data is available from the corresponding author upon

reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest: none

Acknowledgements: I would like to thanks Dr. Luciano Amedée Péret Filho for his kindness in reviewing the text.

Artificial Intelligence: No

REFERENCES

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J; EdS1; Washington A, Patrick M, DiRienzo M et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020 Mar 27;69(4):1-12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 24;69(16):503. PMID: 32214087; PMCID: PMC7119644.

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;63(6):694-701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694. PMID: 16754843.

- Kočovská E, Billstedt E, Ellefsen A, Kampmann H, Gillberg IC, Biskupstø R et al. Autism in the Faroe Islands: diagnostic stability from childhood to early adult life. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:592371. doi: 10.1155/2013/592371. Epub 2013 Feb 17. PMID: 23476144; PMCID: PMC3586480.

- Kleinman JM, Ventola PE, Pandey J, Verbalis AD, Barton M, Hodgson S et al. Diagnostic stability in very young children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008 Apr;38(4):606-15. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0427-8. Epub 2007 Oct 9. PMID: 17924183; PMCID: PMC3625643.

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Landa RJ, Brian J, Bryson S, Charman T et al. Diagnostic stability in young children at risk for autism spectrum disorder: a baby siblings research consortium study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015 Sep;56(9):988-98. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12421. Epub 2015 Apr 29. PMID: 25921776; PMCID: PMC4532646.

- Klin A, Lang J, Cicchetti DV, Volkmar FR. Brief report: Interrater reliability of clinical diagnosis and DSM-IV criteria for autistic disorder: results of the DSMIV autism field trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000 Apr;30(2):163-7. doi: 10.1023/a:1005415823867. PMID: 10832781.

- Canal-Bedia R, Magan-Maganto M, Bejarano-Martin A, De Pablos-De la Morena A, Bueno-Carrera G, Manso-De Dios S et al. Deteccion precoz y estabilidad en el diagnostico en los trastornos del espectro autista [Early detection and stability of diagnosis in autism spectrum disorders]. Rev Neurol. 2016;62 Suppl 1:S15-20. Spanish. PMID: 26922953.

- Volkmar F, Chawarska K, Klin A. Autism in infancy and early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:315-36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070159. PMID: 15709938.

- Westman Andersson G, Miniscalco C, Gillberg C. Autism in preschoolers: does individual clinician’s first visit diagnosis agree with final comprehensive diagnosis? ScientificWorldJournal. 2013 Sep 4;2013:716267. doi: 10.1155/2013/716267. PMID: 24082856; PMCID: PMC3777121.

- Zwaigenbaum L, Bryson SE, Brian J, Smith IM, Roberts W, Szatmari P, Roncadin C, Garon N, Vaillancourt T. Stability of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder between 18 and 36 months in a high-risk cohort. Autism Res. 2016 Jul;9(7):790-800. doi: 10.1002/aur.1585. Epub 2015 Nov 27. PMID: 26613202.

- Piven J, Harper J, Palmer P, Arndt S. Course of behavioral change in autism: a retrospective study of high-IQ adolescents and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Apr;35(4):523-9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00019. PMID: 8919715.

- Cox A, Klein K, Charman T, Baird G, Baron-Cohen S, Swettenham J, Drew A, Wheelwright S. Autism spectrum disorders at 20 and 42 months of age: stability of clinical and ADI-R diagnosis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999 Jul;40(5):719-32. PMID: 10433406.

- Stone WL, Lee EB, Ashford L, Brissie J, Hepburn SL, Coonrod EE, Weiss BH. Can autism be diagnosed accurately in children under 3 years? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999 Feb;40(2):219-26. PMID: 10188704.

- Eaves LC, Ho HH. The very early identification of autism: ra to age 4 1/2-5. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004 Aug;34(4):367-78. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000037414.33270.a8. PMID: 15449513.

- Sutera S, Pandey J, Esser EL, Rosenthal MA, Wilson LB, Barton M et al. Predictors of optimal outcome in toddlers diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007 Jan;37(1):98-107. doi: 10.1007/s10803006-0340-6. Epub 2007 Jan 6. PMID: 17206522.

- Turner LM, Stone WL. Variability in outcome for children with an ASD diagnosis at age 2. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;48(8):793-802. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01744.x. PMID: 17683451.

- Itzchak EB, Zachor DA. Change in autism classification with early intervention: Predictors and outcomes. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009 Oct 1;3(4):967-76.

- Rondeau E, Klein LS, Masse A, Bodeau N, Cohen D, Guilé JM. Is pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified less stable than autistic disorder? A meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011 Sep;41(9):1267-76. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1155-z. PMID: 21153874.

- Rutter M, Greenfeld D, Lockyer L. A five to fifteen year follow-up study of infantile psychosis. II. Social and behavioural outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 1967 Nov;113(504):1183-99. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1183. PMID: 6075452.

- Starr, E.M., Popovic, S. & McCall, B.P. Supporting Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder at Primary School: Are the Promises of Early Intervention Maintained?. Curr Dev Disord Rep 3, 46–56 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-016-0069-7

- Tsai LY, Beisler JM. The development of sex differences in infantile autism. Br J Psychiatry. 1983 Apr;142:373-8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.142.4.373. PMID: 6850175.

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 Feb;45(2):212-29. doi: 10.1111/j.14697610.2004.00215.x. PMID: 14982237.

- Van Wijngaarden-Cremers PJ, van Eeten E, Groen WB, Van Deurzen PA, Oosterling IJ, Van der Gaag RJ. Gender and age differences in the core triad of impairments in autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014 Mar;44(3):627-35. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1913-9. PMID: 23989936.

- Kirkovski M, Enticott PG, Fitzgerald PB. A review of the role of female gender in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013 Nov;43(11):2584-603. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1811-1. PMID: 23525974.

- Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Ruigrok AN, Chakrabarti B, Wheelwright SJ, Auyeung B et al. Cognition in males and females with autism: similarities and differences. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047198. Epub 2012 Oct 17. PMID: 23094036; PMCID: PMC3474800.

- Banach R, Thompson A, Szatmari P, Goldberg J, Tuff L, Zwaigenbaum L, Mahoney W. Brief Report: Relationship between non-verbal IQ and gender in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009 Jan;39(1):188-93. doi: 10.1007/s10803-0080612-4. Epub 2008 Jul 2. PMID: 18594959.

- Rutherford M, McKenzie K, Johnson T, Catchpole C, O’Hare A, McClure I et al. Gender ratio in a clinical population sample, age of diagnosis and duration of assessment in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016 Jul;20(5):628-34. doi: 10.1177/1362361315617879. Epub 2016 Jan 29. PMID: 26825959.

- Amiet C, Gourfinkel-An I, Bouzamondo A, Tordjman S, Baulac M, Lechat P, Mottron L, Cohen D. Epilepsy in autism is associated with intellectual disability and gender: evidence from a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Oct 1;64(7):577-82. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.030. Epub 2008 Jun 20. PMID: 18565495.

- Lukmanji S, Manji SA, Kadhim S, Sauro KM, Wirrell EC, Kwon CS et al. The co-occurrence of epilepsy and autism: A systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. 2019 Sep;98(Pt A):238-248. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.07.037. Epub 2019 Aug 6. PMID: 31398688.

- Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D, Troge J, Lese-Martin C, Walsh T et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science. 2007 Apr 20;316(5823):445-9. doi: 10.1126/science.1138659. Epub 2007 Mar 15. PMID: 17363630; PMCID: PMC2993504.

- Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Araki Y, Lin DT, Yoshizawa Y, Higashi K et al. Excess of de novo deleterious mutations in genes associated with glutamatergic systems in nonsyndromic intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Mar 11;88(3):30616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.001. Epub 2011 Mar 3. Erratum in: Am J Hum Genet. 2011 Apr 8;88(4):516. PMID: 21376300; PMCID: PMC3059427.

- R Core Team R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.Rproject.org/.

- Modabbernia A, Velthorst E, Reichenberg A. Environmental risk factors for autism: an evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Mol Autism. 2017 Mar 17;8:13. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0121-4. PMID: 28331572; PMCID: PMC5356236.

- Forthun I, Strandberg-Larsen K, Wilcox AJ, Moster D, Petersen TG, Vik T et al. Parental socioeconomic status and risk of cerebral palsy in the child: evidence from two Nordic population-based cohorts. Int J Epidemiol. 2018 Aug 1;47(4):1298-1306. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy139. PMID: 29947785; PMCID: PMC6124619.

- Hjern A, Thorngren-Jerneck K. Perinatal complications and socio-economic differences in cerebral palsy in Sweden – a national cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2008 Oct 30;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-8-49. PMID: 18973666; PMCID: PMC2585078.

- Harstad E, Hanson E, Brewster SJ, DePillis R, Milliken AL, Aberbach G et al. Persistence of Autism Spectrum Disorder From Early Childhood Through School Age. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Nov 1;177(11):1197-1205. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4003. PMID: 37782510; PMCID: PMC10546296.

- De Giacomo A, Fombonne E. Parental recognition of developmental abnormalities in autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998 Sep;7(3):131-6. doi: 10.1007/s007870050058. PMID: 9826299.

- Jang J, Matson JL, Cervantes PE, Konst MJ. The relationship between ethnicity and age of first concern in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014 Jul 1;8(7):925-32.

- Petriti U, Dudman DC, Scosyrev E, Lopez-Leon S. Global prevalence of Rett syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2023 Jan 16;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02169-6. PMID: 36642718; PMCID: PMC9841621.

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, Hechtman LT, Kennedy TM, Owens E et al. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032. Epub 2021 Aug 13. PMID: 34384227; PMCID: PMC8810708.

1Fundação Hospitalar de Minas Gerais, Brazil

(camargos1954@gmail.com)

ORCID ID: 0009-0008-6674-1289