REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/ch10202408291233

Renata Cristina Lacerda Bitencourt1;

Luciano Machado-Oliveir2;

Thaurus Vinícius de Oliveira Cavalcanti3;

José Cristiano Faustino dos Santos4;

Paulo Roberto Cavalcanti Carvalho.5

Abstract

Background: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NTC) is an oncological treatment provided prior to surgery. Typically, it is administered for inflammatory and locally advanced tumors, allowing a surgical approach with greater breast tissue preservation. This research aimed to determine the weight profile of women breast cancer survivors during and after NTC treatment and to determine if there were differences in the weight change compared to patients who did not undergo this treatment. Methods: This is a cross-sectional observational study in patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Inclusion criteria were female participants aged 18 to 65 years diagnosed with breast cancer. Patients with type II diabetes, cognitive impairment, functional constraints that hindered assessment, and remote metastasis were excluded. Patients were divided into two groups: those receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy and those not receiving this treatment (control). The instruments used were the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, Waist-Hip Ratio, and body mass index. Results: Sixty women diagnosed with breast cancer were evaluated. There was no significant difference in weight (p = 0.578), body mass index (p = 0.578), waist circumference (p = 0.423), hip circumference (p = 0.176), waist-hip ratio (p = 0.904) after one month of surgery. The patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment did not lose weight. Conclusions: It was not possible to observe a significant difference between the groups that underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the group that did not, after one month of surgery as to weight, body mass index, waist circumference, hip circumference, and waist-hip ratio. It was not possible to observe weight loss during neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment. The findings indicate that the use of NTC has no effect on the weight, body mass index, waist circumference, hip circumference, or waist-hip ratio of women breast cancer survivor, during and after surgical treatments. There is a need for more studies with extended durations and larger sample size.

Keywords: breast cancer; neoadjuvant chemotherapy; weight regain

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is characterized by the uncontrolled growth of cells that can invade neighboring tissues and organs throughout the body, being the most common type of female cancer in the world. According to the different biology, tumours can be classified as luminal A, luminal B, receptor 2 of positive (HER2+), or triple negative 2 human epidermal growth factor1,2

Cancer treatment, which aims to increase disease-free survival while reducing mortality, can be systemic (chemotherapy (SC), hormone therapy, andbiological therapy), and/or local (surgery and radiotherapy) being indicated together or separately for women or men diagnosed with BC³.Furthermore, there is neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NTC), which is administered prior to surgery for inflammatory and locally advanced tumours, allowing a surgical approach with greater conservation of breast tissue4. In addition, NTC has been provided to patients with HER-2+ and triple negative malignancies, with a higher probability of complete pathological response4-7.

Obesity is a risk factor for breast cancer, which increases the chances of developing metastasis and diminishes the complete pathological response to treatment with NTC8,9. Such harm can be observed in different histopathological profiles, including those with positive, HER2+, or triple negative hormone receptors10.

There are indications that weight gain during chemotherapy treatment may be related to reduced survival and an increased risk of disease recurrence through obesity-induced proliferation of neoplastic cells10-¹². Despite being aware of the relationship between obesity and breast cancer, weight variation in patients who underwent NTC remains unclear in the literature; in addition, confounding factors such as other systemic treatments; therefore, additional studies are required to measure possible weight changes and establish a pattern for weight gain or loss for health professionals responsible for such interventions.

Thus, this research aimed to determine the weight profile of women BC survivors during and after NTC treatment and to determine if there were differences in the weight change compared to patients who did not undergo this treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional, observational study that evaluated women who had done or not NTC before breast cancer surgery. Data collection began in December 2020 and ended in June 2021 at the Hospital de Câncer de Pernambuco (HCP). Inclusion criteria were female participants aged 18 to 65 years diagnosed with breast cancer. Patients with type II diabetes, cognitive impairment, functional constraints that hindered assessment, and remote metastasis were excluded.

The research was divided into three moments: T1, prior to NTC; T2, prior to; and T3, one month after surgery. T2 was conducted in the pre-surgical hospitalization, in the breast ward, and T3 was scheduled and performed in an outpatient clinic one month later, with data collected by a single evaluator. Only the variable weight before NTC was retrospectively collected from the record at the T1 time point, but the same scale was used for all assessments.

Patients were divided into two groups: those receiving NTC (NTC) and those not receiving this treatment (control). In the first and second moments, anthropometric measurements and a lifestyle and physical activity questionnaire were administered. In addition, information regarding the patients’ age, menopausal status, hormone receptors, tumour stage, and received treatment was extracted from their medical records.

Information on patients’ age, menopausal status, hormone receptors, tumour stage, and treatment received were obtained from the patients’ medical records. We adopted the Tumour-Node-Metastasis (TNM) classification of BC stage at diagnosis, as established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer – AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY, 2020¹³.

Anthropometric data were measured in T2 and T3 moments. Weight and height measurements were collected using a Welmy class III digital scale. The measurement was performed with the women positioned upright and heels together. From these data, the BMI was calculated by dividing the weight by the height squared, this was classified according to the World Health Organization as low weight for the participants with BMI <18.5, eutrophic with BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/ m2, overweight with a BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2, and obese with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2¹4. Waist circumference was measured using an inelastic tape around the mid area between the last costal arch and the iliac crest and not compressing the skin. Hip circumference was measured using the same tape on the widest part of the buttocks. These data were also used to calculate the Waist-Hip Ratio (WHR).

To measure the level of physical activity, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)¹5,16 was used, and lifestyle was assessed using the fantastic lifestyle questionnaire17.

Data analysis was performed using the Jamovi software v2.3.21 (The jamovi project, 2023 https://www.jamovi.org). The graphics was constructed using the GraphPad Prism 8.2.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Continuous variable was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), the categorical ones was present as absolute and relative frequencies. To verify the data normality the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed. Differences between groups in the baseline was verified with the Student’s T test or Man-Whitney U test, for continuous variables, and the Chi-Square test was performed to verify association between groups for the categorical variables. Intragroup differences across the time were tested using the Student’s T test or Wilcoxon’s test. For the weight variable in the NTC group the one-way ANOVA for repeated measures was performed to verify differences at the three timepoints. To evaluate differences between groups after the treatment, the change values between follow-up and baseline was calculated and a Student’s T test or Mann-Whitney U test was performed. To all tests performed a 5% significance level was adopted.

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital do Câncer de Pernambuco (CAAE: 38726020.5.0000.5205 and approval report 4,404,211). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

3. Results

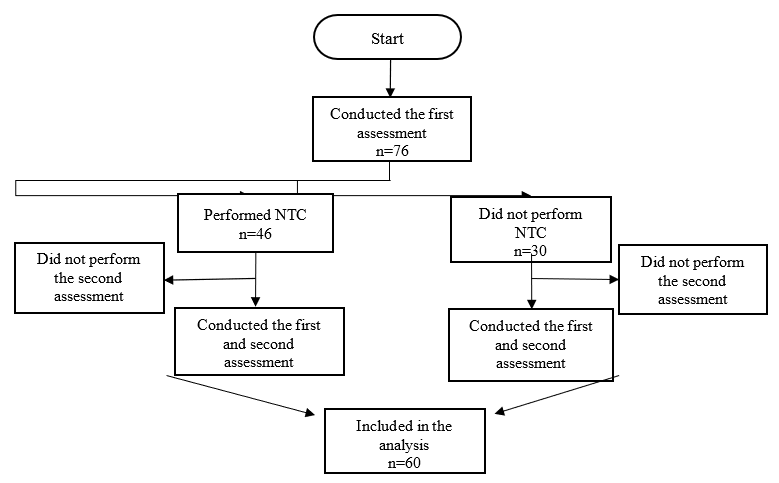

Seventy-six patients were analyzed in the first evaluation, of whom 16 did not undergo the second evaluation, leaving 60 of them who were included in the analysis (age 48.4 ± 8.2 years) and who completed the first and second stages (Figure 1). Thirty-six patients (60.0%) underwent the NTC, while the remaining 24 (40%) who did not undergo that procedure were allocated to the control group. All patients who participated in the present study reported no changes in their habits after the surgery.

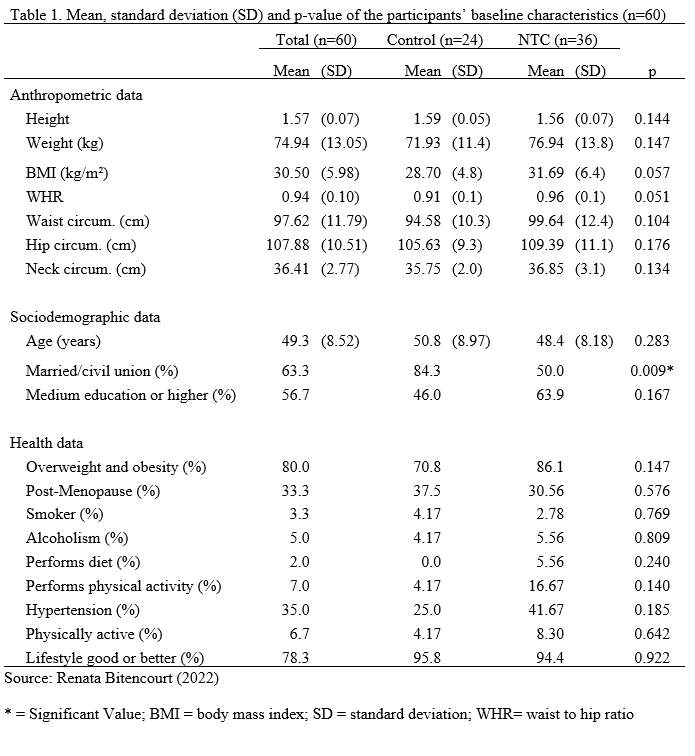

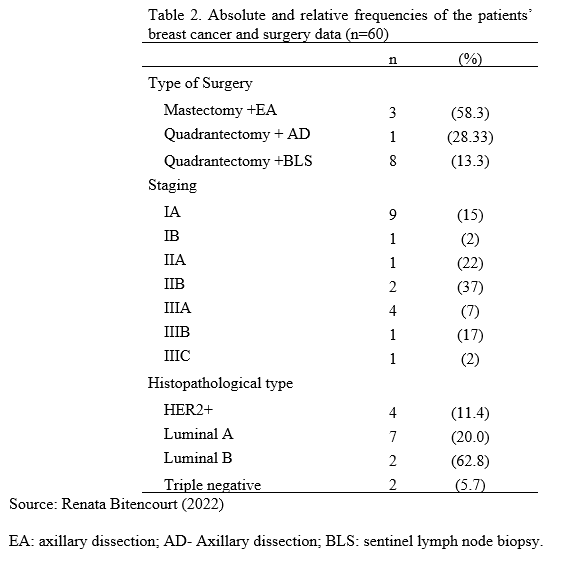

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the sample. Participants were mostly married (63.3%); completed the medium education or higher (56.7%); reproductive age (66,7%); sedentary (51.7%); in a very good lifestyle (45%); and with obesity (56.7%). There was a significant association between marital status and the groups, with more single participants than expected in the NTC group (X2 = 6.89; p = 0.009). There were no other variables with statistically significant association. Most patients underwent mastectomy with axillary dissection (58.3%) and had histopathological type luminal B (62.8%) (Table 2). Doxorubicin, Cyclophosphamide, Docetaxel, and Herceptin were the medications utilized in the NTC.

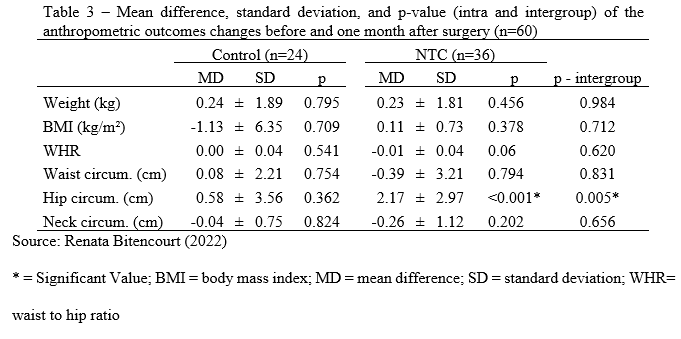

There were no significant changes between follow-up and baseline anthropometric outcomes in the Control group. The hip circumference in the NTC group was larger one month after surgery than before (Z = 509.5; p 0.001). When comparing the changes across groups before and one month after surgery, a significant difference in hip circumference was found (U = 248.0; p = 0.005), with the NTC group showing a higher increase (Table 3). There were no additional significant differences detected (Table 3).

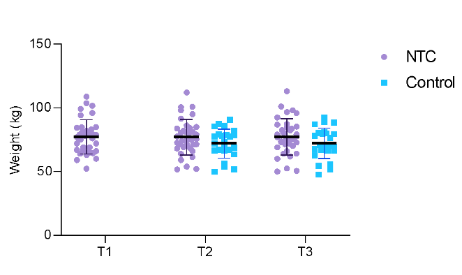

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in individual weight between time points for the two groups. When only the three time points for the NTC group were included, the one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences (F [1.2, 42.0] = 0.094; p = 0.806). Fourteen (40%) patients lost weight, 16 (45.71%) gained weight, and 4 (11.42%) did not change their weight by more than 100 grams during the NTC.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we determined the weight profile of female breast cancer survivors during and after NTC therapy, as well as whether the weight change differed from that of patients who did not receive this treatment. We observed a higher prevalence of patients classified as sedentary, with obesity, and premenopausal, and that most cancer stages were greater than IIA. The most common type of surgery was a mastectomy, and the most significant finding was the absence of a relationship between NTC and variation in anthropometric measurements.

According to the IPAQ questionnaire, the vast majority of patients were either sedentary or insufficiently active. This result was observed in our study because most patients were either sedentary or insufficiently active19. Thus, we determined through the BMI classification that the majority of patients were obese or overweight, a factor that is always linked to inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle. This finding corroborates the results of a previous study involving 2513 women, of whom 38% were obese, 32% were overweight, and none were physically active.20. Ginzac et al21 investigated 109 women and found that weight variation occurred during NTC, with 10.1% losing weight, 29.4% gaining weight, and 60.6% remaining the same weight. Another study found that 65% of participants maintained a constant weight during various forms of chemotherapy22. Our data revealed little variation among patients. In studies that evaluated weight variation during adjuvant and neoadjuvant systemic treatment, weight gain was observed between the first moment of treatment and at the end of it23-25. However, the present study showed a loss of 0.3 kg during NTC.

According to previous research, systemic therapy side effects such as nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, dysphagia, mucositis, loss of appetite, and decreased taste can all contribute to weight loss26-29. The reestablishment of appetite and taste occurs roughly two months after therapy ends28. Another factor that can contribute to an unwillingness to engage in physical activity is anemia caused by chemotherapy30.

There was no significant difference in weight, BMI, waist circumference, or WHR between the NTC and control groups. Both groups gained weight, although there was no trend toward larger increase in the NTC group one month following surgery. In the NTC group, there was a considerable increase in hip circumference. Some studies demonstrate adipose tissue redistribution after chemotherapy31-33. In the same population and treatment period, no studies with an increase just in hip circumference were identified.

Pedersen et al.34 found that patients who underwent SC gained weight and had a larger waist circumference after treatment, but no comparisons were made with patients who did not undergo SC. In contrast, a study revealed that chemotherapy patients were more likely to acquire weight than those who did not receive this treatment35,36. After being diagnosed with breast cancer, women have a higher tendency to reduce their physical activity levels. Assisted by the fact that the resting metabolic rate is decreased37,38. WHR increased in both groups, with greater intensity in the NTC group. Another study with BC patients observed a 1.1 increase in WHR after treatment, but did not categorize them into groups and treatment39,40.

The current study has some limitations, such as a small sample size and a short follow-up period. Because the data was collected during the COVID-19 outbreak, some of the results were more descriptive in nature. Larger sample size studies with longer follow-up period are now required. This is the first study to compare weight gain following surgery between two groups, including patients who did not receive NTC, and without interference from other therapies. Weight gain or loss is becoming more investigated and linked to disease-free survival. The study highlights the need for additional research that compares treatment groups and their impact on weight gain.

5. Conclusions

Higher prevalence of sedentary lifestyle, obesity and low level of physical activity were found among women who survived breast cancer. We did not observe significant differences between the groups that underwent NTC and the group that did not undergo NTC after one month of surgery in terms of weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference and WHR. It was also possible to observe that the patients who underwent NTC did not have a significant change in weight during systemic treatment.

Acknowledgements

Financing: there was no financing

Ethical approval

“All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.”

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest

References

1- Instituto Nacional do Câncer (INCA). Available: > https://www.inca.gov.br/tipos-de- cancer/cancer-de-mama. Access on: 26th October, 2023.

2- Reis-Filho, Jorge S, Pusztal L. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. The Lancet, [S.L.], 2011; 378(9805): 1812-1823.doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61539-0.

3- Center of Disease Control and Prevention. Breast Cancer: Basic Information About Breast Cancer. 2019. Disponível em: https://search.cdc.gov/search/index.html?query=breast%20cancer&dpage=1

Acesso em: 01 de out. 2021.

4- AL-HILLI, Zahraa Z, Boughey JC. The timing of breast and axillary surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Chinese Clinical Oncology, 2016; 5(3):37-37.doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.03.26.

5- Fisher BAB, Mamounas E, Wieand S, Robidoux A, Margolese RG, Cruz Jr A B ,et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project b-18.. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 1997;15(7): 2483-2493. doi: 10.1200/jco.1997.15.7.2483.

6- Wolmark N, Wang J, Mamounas E, Bryant J, Fisher B. Preoperative Chemotherapy in Patients With Operable Breast Cancer: nine-year results from national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project b-18. Jnci Monographs, 2001;30:96-102.doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003469.

7- Bear HD, Anderson S, Smith RE,Geyer Jr CE, Mamounas EP, Fisher B, et al. Sequential Preoperative or Postoperative Docetaxel Added to Preoperative Doxorubicin Plus Cyclophosphamide for Operable Breast Cancer: national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project protocol b-27. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2006; 24(13):2019- 2027. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.1665.

8- Ewertz M, Gray KP, Regan MM, Ejlertsen B, Price KN, Thürlimann B, et al. Obesity and Risk of Recurrence or Death After Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy With Letrozole or Tamoxifen in the Breast International Group 1-98 Trial. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2012;30(32): 3967-3975. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.40.8666.

9- Ewertz M, Jensen MB, Gunnarsdóttir KÁ, Højris I, Jakobsen EH, Nielsen D, et al. Effect of Obesity on Prognosis After Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2011;29(1):25-31. doi:10.1200/jco.2010.29.7614.

10- Thivar E, Thérondel S, Lapirot O, Abrial G, Gimbergues P, Gadéa E, et al. Weight change during chemotherapy changes the prognosis in non metastatic breast cancer for the worse. Bmc Cancer, 2010; 10(1): 648-648. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-648.

11- Litton JK, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Warneke CL, Buzdar AU, Kau SW, Bondy M, et al. Relationship Between Obesity and Pathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Among Women With Operable Breast Cancer. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2019; 26 (25):4072-4077.doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.14.4527.

12- Gadéa E, Thivat E, Planchat E, Morio B, Durando X. Importance of metabolic changes induced by chemotherapy on prognosis of early-stage breast cancer patients: a review of potential mechanisms. Obesity Reviews, 2011; 13(4): 368-380. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2011.00957.x.

13. American Cancer Society. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/staging.html. Access on: 1st September, 2020.

14- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Fact Sheet 311 (Reviewed May 2014). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. Access on: 19th December, 2021.

15-Matsudo S, Araujo T; Matsudo V, Andrade D, Andrade E; Oliveira LC, et al. Questionário Internacional de Atividade Física (IPAQ): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no Brasil. Rev Bras Ativ Saude.2001; 10: 5-18.doi:10.12820/rbafs.v.6n2p5-18.

16- Ruiz-Casado A, Alejo L, Santos-Lozano A, Soria A, Ortega M J , Pagola I, et al. Validity of the Physical Activity Questionnaires IPAQ-SF and GPAQ for Cancer Survivors: insights from a spanish cohort. International Journal Of Sports Medicine, 2016; 37(12):979-985. doi: 10.1055/s- 0042-103967.

17-Rodriguez Añez CR, Reis RS, Petroski EL. Versão brasileira do questionário "estilo de vida

fantástico": tradução e validação para adultos jovens. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. Ago 2008;91(2). doi: 10.1590/s0066-782×2008001400006

18- Canário ACG, Cabral PUL, Paiva LC, Florencio GLD, Spyrides MH, Gonçalves AKS. Physical activity, fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, 2016; 62(1):38-44.doi:10.1590/1806-9282.62.01.38.

19- Redden MH, Fuhrman GM. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Breast Cancer.

Surgical Clinics Of North America, 2013; 93(2):493-499. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2013.01.006.

20-Patel V, James M, Frampton C, Robinson B, Davey V, Timmings L. Body Mass Index and Outcomes in Breast Cancer Treated With Breast Conservation. International Journal Of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, 2020; 106(2):369-376. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.09.049.

21- Ginzac A, Barres B, Chanchou M, Gadéa E, Molnar I, Merlin C. A decrease in brown adipose tissue activity is associated with weight gain during chemotherapy in early breast cancer patients. Bmc Cancer, 2020; 20(1):96- 96, 4 fev. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6591-3.

22- Chaudhary LN, Wen S, Xiao J, Swisher AK, Kurian S, Abraham J. Changes in body weight during various types of chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. E-Spen Journal, 2014; 9(1):39-44. doi:10.1016/j.clnme.2013.10.004.

23- Custódio DD, Franco FP, Marinho EC, Pereira TSS, Lima MTM, Molina MCB, et al. Prospective Analysis of Food Consumption and Nutritional Status and the Impact on the Dietary Inflammatory Index in Women with Breast Cancer during Chemotherapy. Nutrients, 2019; 11(11): 2610. doi:10.3390/nu11112610.

24- Custódio SDD, Marinho EC, Gontijo CA, Pereira TSS, Paiva CE, et al. Impact of Chemotherapy on Diet and Nutritional Status of Women with Breast Cancer: a prospective study. Plos One, 2016; 11(6): 0157113. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157113.

25- Silva BR, Rufato S, Mialich MS, Cruz LP, Gozzo T, Jordao AA. Metabolic syndrome and unfavorable outcomes on body composition and in visceral adiposities indexes among early breast cancer women post- chemotherapy. Clinical Nutrition Espen, 2021; 44:306-31. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.06.001.

26- Denda Y, Niikura N, Satoh-Kuriwada S, Yokoyama K, Terao M, Morioka T, et al. Taste alterations in patients with breast cancer following chemotherapy: a cohort study. Breast Cancer, 2020; 27(5):954-962.doi:10.1007/s12282-020-01089-w.

27- Boltong A, Aranda S, Keast R, Wynne R, Frances PA,Chirgwin J, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study of the Effects of Adjuvant Breast Cancer Chemotherapy on Taste Function, Food Liking, Appetite and Associated Nutritional Outcomes. Plos One, 2014; 9(7):103512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103512.

28- Sánchez LK, Ugalde ME, Motola-Kuba D, Green D. Gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss in

cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. British Journal Of Nutrition, 2012;109(5): 894-897. doi:10.1017/s0007114512002073.

29- Silva GSF, Bergamaschine R, Rosa M, Melo C, Miranda R , Filho MB. Avaliação do nível de atividade física de estudantes de graduação das áreas saúde/biológica. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte, 2007; 13(1):39- 42. doi: 10.1590/s1517-86922007000100009.

30-Danzinger S, Fügerl A, Pfeifer C, Bernathova M, Tendl-Schulz K, Seifert M. Anemia and Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer Invest. 2021 Jul- Aug;39(6-7):457-465. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2021.1928166.

31-Harvie MN, Campbell IT, Baildam A, Howell A. Energy balance in early breast cancer patients

receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;83(3):201–210. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000014037.48744.

32-Freedman RJ, Aziz N, Albanes D, Hartman T, Danforth D, Hill S, et al. Weight and body composition changes during and after adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;89(5):2248–2253. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003- 031874.

33- Campbell KL, Lane K, Martin AD, Gelmon KA, McKenzie DC. Resting energy expenditure and

body mass changes in women during adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(2):95–100. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000265004.64440.5f

34- Pedersen B, Delmar C, Bendtsen MD, Bosaeus I , Carus A, Falkmer U, et al. Changes in Weight and Body Composition Among Women With Breast Cancer During and After Adjuvant Treatment. Cancer Nursing, 2017; 40(5):369-376. doi: 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000426.

35- Lee K, Kruper L, Dieli-Conwright, Mortimer JE. The Impact of Obesity on Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Current Oncology Reports, 2019: 21(5):41-41.doi: 10.1007/s11912-019- 0787-1.

36- Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K, et al. Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New England Journal Of Medicine, 2016; 375(8):794-798. Massachusetts Medical Society.doi: http:10.1056/nejmsr1606602.

37- Sheng JY, Sharma D, Jerome G, Santa-Maria CA. Obese Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors: Management Considerations. Oncology Williston 2018;.32(8):410-7.

38- Dieli-Conwright CM, WONG L, Waliany S, Bernstein L, Salehian B, Mortimer EJ. An observational study to examine changes in metabolic syndrome components in patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer, 2016;122(17):2646-2653. doi:10.1002/cncr.30104.

39- Griggs JJ, Mangu PB, Anderson H, Balaban EP, Dignam JJ, Hryniuk WM, et al. Appropriate Chemotherapy Dosing for Obese Adult Patients With Cancer: american society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2012; 30(13):1553-1561. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.39.9436.

40- Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, André F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, et al. Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy and Long-Term Survival in Patients With Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Journal Of Clinical Oncology, 2008; 26(8):1275-1281. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.14.4147.

Tables

Figures

Figure 1 – Flowchart for collecting participants

NTC – Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Figure 2 – Individual body mass in the different timepoints of the NTC and control groups. The bars represent mean and standard deviation.

1Postgraduate Program in Surgery, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil, renata02bitencourt@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0951-859X;

2Federal University of Pernambuco, Vitória de Santo Antão, Pernambuco, Brazil;

3Postgraduate Program in Surgery, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil;

4Postgraduate Program in Surgery, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil;

5Postgraduate Program in Surgery, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil