REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/ni10202511292312

Antonio Clareti Pereira1

ABSTRACT

Static liquefaction remains a primary cause of catastrophic failures in tailings storage facilities (TSFs) and fine-ore deposits, creating serious technical, environmental, and social consequences. Between 2020 and 2025, substantial advances have been achieved in experimental testing, in situ characterization, numerical modeling, and case-history interpretation, yet major knowledge gaps persist. Recent evidence shows that traditional approaches that focus solely on triggers, such as rapid loading or water-level changes, cannot explain delayed failures. The Brumadinho case, for example, demonstrated that gradual slipsurface formation and creep under nearly constant load were dominant factors. CPTu-based correlations have improved estimation of state parameters and liquefied strength, but their application to highly layered or cemented tailings remains uncertain. Laboratory triaxial and ring-shear tests have refined steady-state strength models, though results vary with particle size, fines content, and depositional history. Advanced large-deformation numerical tools (PFEM, MPM) have enhanced understanding of failure initiation and run-out, but coupling hydrogeological and geomechanical processes remains challenging. Regulatory frameworks such as the GISTM (2020) and Brazil’s ANM Resolution 95/2022 have strengthened oversight; however, implementation is uneven. Future progress depends on integrating laboratory and field observations, standardizing liquefaction-assessment protocols, and enforcing continuous monitoring.

Keywords: static liquefaction, mine tailings, state parameter (ψ), CPTu, steady-state strength, ring shear test, progressive failure, numerical modeling, regulatory frameworks

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Managing mine tailings presents a major challenge for the mining industry due to the large quantities involved and the potentially devastating consequences of TSF (tailings storage facility) failures. Static liquefaction is identified as a leading cause of these failures, alongside overtopping and dynamic (cyclic) liquefaction (Adria et al. 2023). It happens when saturated, contractive tailings abruptly lose shear strength under monotonic undrained loading, resulting in rapid deformation and flow slides (Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas 2023). Tailings are especially susceptible because they are often deposited with high water content and low density, conditions that encourage strain softening and the buildup of excess pore pressure when shear stress is exerted (Association of State Dam Safety Officials 2021–2024).

The concept of static liquefaction originates from Critical State Soil Mechanics (CSSM) and steady-state deformation theory. These approaches utilize the state parameter (ψ) to assess how far the current void ratio is from the critical state line, aiding in determining whether the soil tends to compact or expand under stress (Ayala et al. 2022; Ayala et al. 2023a). Recent research has enhanced the understanding of the connection between ψ and liquefaction potential, particularly through field techniques like the cone penetration test (CPTu) (Ayala et al. 2023b).

Earlier reviews by Santamarina et al. (2019), Fourie et al. (2023), and Verdugo (2020, 2021) laid the foundation for understanding liquefaction in mine tailings. Santamarina focused on geotechnical fundamentals, such as flow failures, emphasizing the relationships among density, fines, and drainage. Fourie et al. (2023) provided a practical perspective, linking laboratory data to tailings management strategies. Verdugo examined steady-state and criticalstate theory, stressing their importance for stability assessments. However, these works mainly studied mechanical or geotechnical aspects separately and did not fully incorporate hydrogeological feedback, numerical modeling, or governance frameworks developed after 2020.

From 2020 to 2025, notable advances occurred in understanding static liquefaction. Experimental studies explored how variables like fines content, particle size distribution, and depositional history affect undrained strength and static liquefaction resistance (Ayala et al., 2023b; Barros et al., 2024). Numerical modeling, utilizing large-deformation finite element methods (FEM) and particle-based techniques such as the particle finite element method (PFEM) and the material point method (MPM), improved simulation of failure initiation and development (Been & Jefferies, 1985; Sordo et al., 2025). The 2019 Brumadinho disaster case study demonstrated that some failures do not happen instantly but evolve gradually over time, mainly due to creep and the slow growth of slip surfaces under nearly constant loads (CDA 2021).

Globally, oversight and regulatory frameworks have expanded to become more comprehensive. The Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM, 2020) outlines a detailed lifecycle oversight framework, highlighting transparency, water balance management, and stakeholder engagement (Clarkson & Williams, 2021). In Brazil, ANM (Agência Nacional de Mineração) Resolution No. 95/2022 introduced stricter monitoring and risk assessment protocols, especially for static liquefaction (Consoli et al., 2024). These developments indicate a transition from traditional factor-of-safety analyses toward risk-based, performance-oriented management strategies.

This review critically analyzes literature on static liquefaction, emphasizing mechanisms, assessment methods, numerical modeling, and governance practices. Unlike earlier reviews, it uniquely integrates mechanical, hydrogeological, and governance viewpoints, offering a comprehensive framework for managing static liquefaction risks.

2. Research Methodology

This review uses a systematic literature review (SLR) method following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, aiming to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and traceability in data selection (Adria et al., 2023). The process includes four main stages, supported by quantitative filtering and detailed documentation of decision steps (Page et al., 2021). This review mainly focuses on studies, technical reports, and regulatory frameworks published between 2020 and 2025, reflecting the latest advances in static liquefaction research, laboratory testing, numerical modeling, and governance practices. However, a limited number of pre-2020 references are also included due to their fundamental relevance or ongoing influence on regulatory standards and governance frameworks (e.g., the development of the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management and early critical-state formulations). These earlier sources provide the conceptual foundation for interpreting recent findings and maintaining continuity among empirical, theoretical, and policy developments.

2.1. Definition of scope and keywords

The review concentrated on research related to the static liquefaction of mine tailings and fine-grained ores subjected to monotonic undrained loading. Key terms included “static liquefaction,” “tailings,” “flow failure,” “state parameter,” “critical state,” “steady state line,” and “CPTu tailings.” To encompass regional literature from South America, synonyms in Portuguese and Spanish were also utilized, broadening the scope to include national reports and theses.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included:

- Empirical data (laboratory or field), case studies, or numerical simulations.

- Peer-reviewed or officially published regulatory documents.

Excluded:

- Studies focusing only on cyclic liquefaction (unless comparative).

- Non-technical commentaries or untraceable online sources.

- Grey literature lacks methodological rigor.

2.3. Data extraction and synthesis

Each study was categorized based on material type, testing method, geotechnical parameters, triggering conditions, and key findings. These were then grouped into four main themes, resulting in four thematic pillars.

- Mechanisms and microstructure

- Assessment and monitoring of lab and CPTu/ψ correlations.

- Numerical modeling and runout analysis

- Governance and regulatory structures

Data were normalized, where applicable, to enable easier comparison of steady-state strength ratios (Su/σ′v0), the state parameter (ψ), and residual strength envelopes.

3. Physical Mechanisms and Microstructure

3.1. Effects of Microstructure and Fines Content

The microstructure, particle interactions, and boundary conditions are crucial factors in triggering static liquefaction in mine tailings. When contractive soils undergo monotonic undrained shear, they tend to develop excess pore pressure, reduce effective stress, and cause abrupt strength reduction and flow slides (Ayala et al., 2022; Ayala et al., 2023a; Fourie et al., 2023).

Tailings often exhibit different structures resulting from hydraulic deposition at low density and high saturation, leading to metastable fabrics that can easily collapse with minimal disturbance (ICMM 2021). Fragile or partially cemented bonds—commonly involving iron oxides, sulfates, or silicates—may offer temporary stability but are prone to sudden failure when interparticle connections break. Studies indicate that bimodal tailings, consisting of fine and coarse particles, display two behaviors: fines-rich layers are highly contractive, whereas coarser layers tend to expand. Furthermore, bi-modal tailings with both particle sizes present two distinct patterns: fines-rich layers are very contractive and prone to brittle failure (CDA 2021; Ayala et al., 2023a; Ji et al., 2024; Barros et al., 2024).

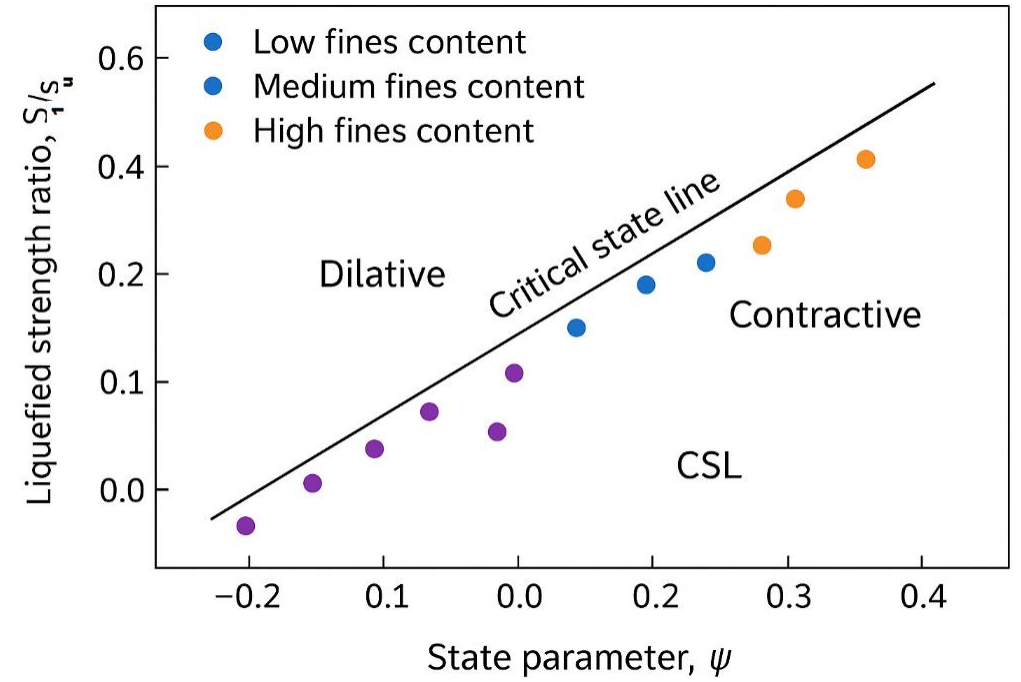

Figure 1 shows an inverse relationship between the state parameter (ψ) and the liquefaction resistance ratio (Sₗ/Sᵤ), combining empirical data with a conceptual basis for evaluating the static liquefaction susceptibility of mine tailings. The X-axis displays ψ, indicating how far the soil state is from the Critical State Line (CSL), while the Y-axis shows Sₗ/Sᵤ, the ratio of strength after liquefaction to the peak undrained shear strength.

Figure 1. Relationship between the state parameter (ψ) and the liquefied strength ratio (Sₗ/Sᵤ), illustrating the transition from dilative to contractive behavior as fines content increases (adapted from Been & Jefferies 1985; Jefferies & Been, 2015; Macedo et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023; Verdugo, 2021)

Two separate behavioral zones are identified:

- The Contractive Zone (ψ > 0) encompasses materials above the CSL that exhibit contractive behavior when subjected to monotonic loading. As ψ rises, pore pressure accumulates more quickly, leading to a rapid reduction in effective stress and a significant decline in liquefied strength (Sₗ/Sᵤ < 0.2). This zone typically signals a high risk of liquefaction, particularly in fine-grained, saturated tailings with low densities.

- Dilative Zone (ψ < 0): Materials below the CSL tend to expand during shear, leading to reduced pore pressures and supporting higher residual strength (Sₗ/Sᵤ > 0.5). These soils exhibit strain-hardening behavior and are less prone to flow failures.

The overall trend indicates that liquefied strength decreases exponentially with increasing ψ, consistent with laboratory findings by Been and Jefferies (1985), Ayala et al. (2022), Yamamuro and Lowe (1998), and Thevanayagam and Riemer (1998). These studies show a consistent exponential decline in the liquefied strength ratio with rising ψ across different tailings gradations.

Critical Analysis

The ψ–Sₗ/Sᵤ relationship provides a more reliable assessment of liquefaction potential than traditional parameters such as relative density or void ratio. Unlike methods that focus solely on density, ψ accounts for the combined effects of structure, confining pressure, and stress history, enabling consistent comparisons across various tailing types and depositional settings.

The correlation relies on empirical data and may vary due to factors such as cementation, anisotropy, and the mineralogy of the fines. For instance, sulfate-rich or oxidized tailings might appear to have high strength at low ψ values but can rapidly fail when bonding breaks down. Therefore, ψ should be assessed alongside hydrogeological data and microstructural observations within a comprehensive multi-parameter framework.

In practice, calibrating ψ with CPTu measurements and laboratory tests enables the development of site-specific liquefaction envelopes. This blend of theoretical and empirical data improves the accuracy of predictions for TSF design and risk assessments.

3.2. Critical State Framework and State Parameter

The CSSM framework provides the theoretical foundation for understanding static liquefaction. It distinguishes between:

- Critical State Line (CSL): The point at which the material experiences constant stress and volume change upon reaching equilibrium.

- Steady-State Line (SSL): The stage where particle rearrangement ceases, and the system reaches full remolding (Ayala et al., 2022; Ayala et al., 2023a).

The state parameter ψ, as defined by Been and Jefferies (1985), measures the difference between the current void ratio and the CSL (Ayala et al., 2022).

- ψ > 0 signifies a material that is contractive, strain-softening, and prone to liquefaction.

- ψ < 0 indicates a material that is dilative, strain-hardening, and stable (Been & Jefferies, 1985; Thevanayagam & Riemer, 1998).

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship among the state parameter (ψ), the Critical State Line (CSL), and the Steady State Line (SSL) in Critical State Soil Mechanics (CSSM). The graph displays the void ratio (e) on the Y-axis and the logarithm of the mean effective stress (log p′) on the X-axis.

Axes and parameters

Y-axis (σ′v) – effective vertical stress, representing the average confining pressure on the soil skeleton. X-axis (e) – void ratio, indicating the soil’s position relative to the CSL. ψ is defined as the vertical distance between the current state and the CSL at the same effective stress.

When ψ < 0, the soil is denser than at the critical state; when ψ > 0, it is looser and more susceptible to instability (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conceptual relationship between the state parameter (ψ), Critical State Line (CSL), and Steady-State Line (SSL), distinguishing dilative and contractive behaviors under different stress and void ratio conditions (adapted from (Been & Jefferies, 1985; Jefferies & Been, 2015; Verdugo, 2021)

Behavioral Zones:

Dilatant zone (orange region) – ψ < 0, where dense soils tend to increase in volume when sheared, resulting in negative pore pressures and an apparent boost in strength. Contractive zone (blue region) – ψ > 0, where loose or contractive soils tend to compress under shear, producing positive pore pressures and risking static liquefaction.

Interpretation and importance

This diagram illustrates how the state parameter ψ functions as a unifying index that connects soil density, confining pressure, and undrained shear behavior. It forms the basis for current methods used to assess static liquefaction susceptibility, especially in the context of mine tailings and other contractive geomaterials.

3.3. Stratification and Progressive Failure

Natural and hydraulic depositional processes create layered strata that alternate between contraction and dilation zones. These variations promote progressive shear localization, where small, weak zones develop into continuous failure planes over time (Association of State Dam Safety Officials 2021–2024, Babaki et al. 2024; Sottile et al., 2020).

Zhu et al. (2025) demonstrated this through the Brumadinho failure, in which creep and local weakening revealed weak zones, ultimately causing a delayed collapse.

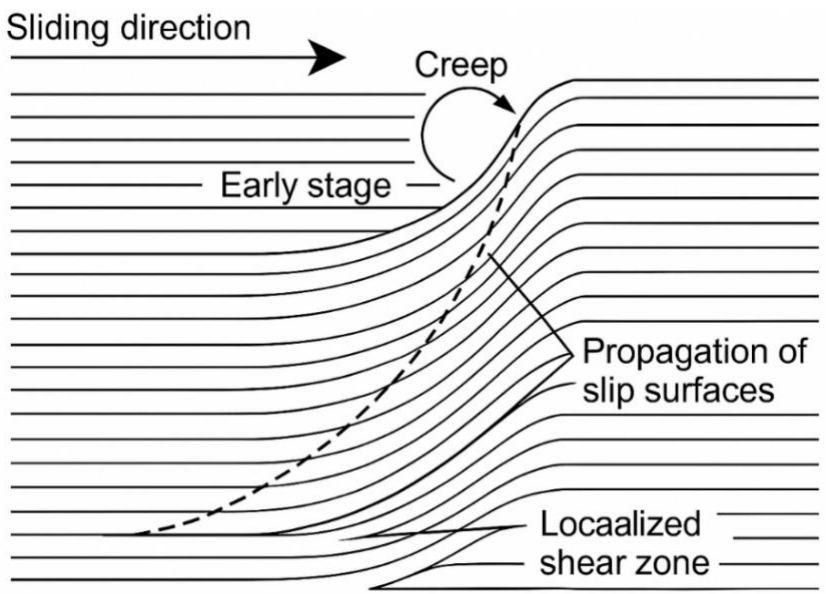

Figure 3 clearly shows the development of shear localization within layered tailings deposits, from initial deformation to the formation of a continuous slip surface. The arrows indicate the direction of sliding and shear strain movement, revealing how localized shear zones come together under continuous or monotonic.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram showing progressive shear localization in layered tailings, highlighting the connection between contractive and dilative layers under sustained or monotonic loading (adapted from Verdugo 2021; Zhu et al. 2024, 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Simms et al., 2025)

- Initial Layering: The deposition process results in alternating layers that vary in density and fines content, which causes differences in permeability and contraction behavior.

- Localized shear starts with initial deformation occurring in weak contractive zones, where pore pressure rises and strain begins to build up.

- Progressive failure occurs as localized zones merge over time or under ongoing load due to creep deformation, leading to the formation of partial slip surfaces.

- Continuous Slip Surface: The failure surface connects several weak layers that extend upward and sideways, ultimately leading to widespread static liquefaction.

Arrows show how shear strain spreads and emphasize the gradual development of local shear bands caused by excess pore pressure buildup. The diagram also differentiates between stable dilative layers, which temporarily resist deformation, and contractive layers, which weaken over time, leading to the formation of a continuous failure plane.

Critical Analysis

This conceptual model indicates that static liquefaction occurs gradually rather than suddenly or uniformly across various regions. It is a time-dependent process. Layered tailings deposits, commonly employed in hydraulic placement, develop zones with distinct mechanical and hydraulic properties. Over time, these zones promote strain localization. The transition from isolated weak zones to a continuous failure surface illustrates the creep-driven mechanism observed in many historical failures, such as the Brumadinho disaster (CDA 2021).

Alternating layers of contraction and dilation act as control mechanisms and triggers for liquefaction. Spread dilative zones temporarily inhibit failure, while contractive zones raise pore pressure and strain energy. This behavior is supported by experimental and numerical evidence from Zhu et al. (2024), Fourie et al. (2023), and Sordo et al. (2025), which show that progressive shear deformation can occur under nearly steady external loads.

These findings emphasize the importance of continuously monitoring pore pressures, displacements, and strain localization in tailings storage facilities (TSFs). Visible stability does not necessarily indicate the absence of subsurface creep-driven failure. This understanding supports the development of early-warning systems that integrate geotechnical, hydrological, and remote-sensing data to detect deformation signs before a significant failure.

3.4. Hydrogeological Feedback and Pore Pressure System

Hydrogeological factors, such as the phreatic surface level, seepage gradients, and drainage capacity, influence pore pressure and effective stress. Fourie et al. (2023) linked high water tables and poor drainage to localized saturation and increased pore pressure. These hydraulic feedback loops decrease shear strength, especially in upstream TSFs with confined and fragile layers (ICMM et al., 2020). Minor disturbances, such as light rain, water-level fluctuations, or operational loads, can lead to instability by increasing pore pressure and decreasing σ’ (Ayala et al., 2022; Fourie et al., 2023).

The cross-sectional schematic (Figure 4) illustrates how rising phreatic levels lead to pore-pressure buildup, reducing effective stress in a TSF. It highlights key features of a typical dam, such as the tailings deposit, an impermeable foundation, seepage pathways, and zones of high pore pressure near the downstream slope. Arrows depict upward and lateral water movement as the phreatic line ascends, while the red-shaded areas indicate regions vulnerable to instability due to increased pore pressure.

Figure 4. Cross-sectional diagram illustrating the rise in phreatic level and resulting porepressure accumulation zones in upstream tailings dams (adapted from Been and Jefferies 1985; Jefferies & Been, 2015; Verdugo, 2021)

Under normal drainage conditions, the phreatic line remains below the downstream slope, providing a safety margin. However, when water inflow surpasses the drainage capacity—caused by rainfall, poor water management, or insufficient internal drains—the phreatic surface elevates. This rise in water level increases saturation and reduces the effective stress (σ′) in the lower tailings layers, typically near the slope toe or drainage barriers.

Critical Analysis

The figure illustrates how hydrogeological feedback loops lead to static liquefaction in mine tailings. A rise in the phreatic surface alters pore-pressure gradients, creating a positive feedback cycle between saturation and contractive behavior. As water levels rise, fine-grained, low-permeability, contractive layers generate excess pore pressure faster than it can dissipate, weakening shear strength and increasing the likelihood of undrained deformation or flow failure (ICMM et al., 2020; Fourie et al., 2023). This conceptual model aligns with hydromechanical studies by Fourie et al. (2023) and Santamarina et al. (2019), which show that even small increases in the phreatic level can decrease the safety factor by up to 40% in upstreamraised dams. Notably, the diagram indicates that instability originates internally, rather than externally, making it a progressive process that may initially be unnoticed. The buildup of hydrogeological pressure, combined with structural heterogeneity, supports the physical mechanism behind static liquefaction.

Moreover, the accumulation zones at the slope toe indicate that poor drainage or blocked underdrains can cause localized increases in hydraulic pressure. These areas are vulnerable to seepage erosion, piping, or reduced effective stress, which could lead to serious failure if not addressed. Therefore, it is crucial to regularly monitor pore-pressure transducers, vibrating-wire piezometers, and phreatic level sensors, in accordance with the guidance provided by ICMM (2021) and CDA (2021).

In summary, Figure 4 shows that the hydrogeological regime acts both as a trigger and an amplifier of static liquefaction potential. Properly designing and managing the phreatic surface—through internal drains, decant systems, and seepage collection galleries—is a crucial preventive measure to maintain long-term TSF stability.

3.5. Time-Dependent Behavior and Creep

Static liquefaction can occur long after deposition or closure, due to creep-induced weakening. When subjected to sustained loads, slip surfaces slowly advance through weakly bonded layers. Zhu et al. (2024,2025) documented delayed failure driven by creep deformation under nearly constant effective stress.

Key observation: Time-dependent deformation acts as an unseen precursor— undetectable through traditional strength-based methods—highlighting the need for real-time monitoring of pore pressures and displacements (CDA 2021, Sottile et al. 2020).

3.6. Synthesis of Physical Factors

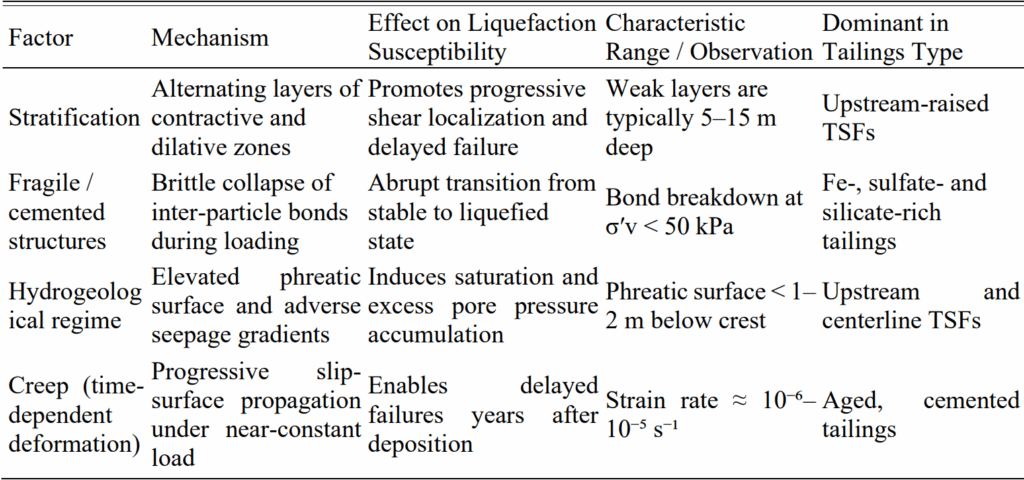

Table 1 summarizes the key physical factors that influence liquefaction initiation, drawing on laboratory data, theoretical studies, and field case histories.

Table 1. Key physical factors affecting static liquefaction susceptibility in mine tailings and fine ores, highlighting the interaction between fines content, structure, and drainage conditions (adapted from Ayala, Fourie, and Reid 2023a; Verdugo, 2021; Consoli et al., 2024; Simms et al., 2025; Sordo et al., 2025)

The table indicates that no single factor suffices independently—static liquefaction results from the interplay of the material’s internal characteristics and external boundary conditions. For instance, a high fines content combined with poor drainage and stratification can create conditions where monotonic shear stresses more readily trigger runaway porepressure feedback. Fragile microstructures and creep also raise the risk of sudden or delayed collapses. These results emphasize the importance of comprehensive assessment methods that integrate geotechnical analysis, hydrogeological modeling, and ongoing monitoring. Relying solely on traditional strength-based approaches may overlook time-dependent factors, potentially underestimating the hazards involved.

In summary, Table 1 provides a framework for recognizing and prioritizing key factors in the design, monitoring, and remediation of tailings storage facilities and fine ore deposits, establishing a foundation for proactive risk management. It illustrates the relationships among the state parameter (ψ), the Critical State Line (CSL), and the Steady State Line, creating a conceptual model to understand the mechanical behavior of mine tailings and fine ores under undrained conditions. This relationship is vital in Critical State Soil Mechanics and is regarded as one of the most dependable methods for evaluating static liquefaction risk (Ayala et al., 2022; Ayala et al., 2023a; Thevanayagam & Riemer, 1998).

3.7. Integrated Conceptual Model

Figure 5 illustrates how microstructural, mechanical, and hydrogeological factors collaborate to induce static liquefaction.

Figure 5. Summary of static liquefaction causes, mechanisms, and lessons learned from recent failures, showing how weak layers, drainage conditions, and strain-softening interact to trigger pore-pressure buildup (adapted from Verdugo 2024; Zhu et al. 2024, 2025; Sreekumar et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024; Simms et al., 2025)

The interaction triangle shows feedback loops: increased pore pressure reduces effective stress, causing strain localization and eventual failure.

4. Experimental Evidence and Strength Parameters

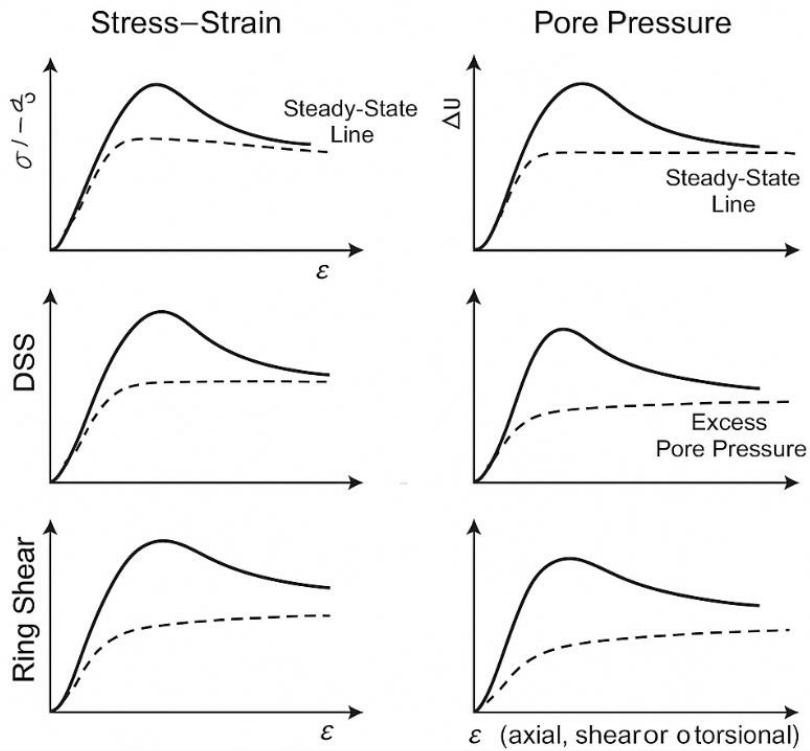

Understanding the undrained response of mine tailings is essential for assessing their static liquefaction risk and establishing safe operational limits for TSFs. Laboratory tests— such as triaxial, direct simple shear (DSS), and ring shear tests—are vital for measuring steadystate strength, residual resistance, and failure mechanisms. These tests show how tailings transition from initial stable conditions to complete strength loss under monotonic loading (Ayala et al., 2023c; Barros et al., 2024; Fourie et al., 2023; Lumbroso et al., 2020).

4.1. Laboratory Techniques

Monotonic triaxial tests are the standard method for assessing undrained shear strength, pore pressure development, and stress–strain behavior. They are essential for establishing the Steady-State Line (SSL) and CSL, which are key components of the CSSM framework (Ayala et al., 2022; Thevanayagam & Riemer, 1998). Usually, contractive tailings show a peak in deviatoric stress, followed by strain softening and a sharp rise in pore pressure—indicators of static liquefaction onset (Ayala et al., 2023c; Fourie et al., 2023). Ring shear tests, capable of applying large strains, provide more realistic estimates of residual strength after liquefaction (Macedo et al., 2022). These tests simulate continuous shearing conditions typical in actual runout events, enhancing the calibration of numerical models. Additionally, direct simple shear (DSS) tests give valuable insights under horizontal shear stress paths common in layered tailings, facilitating a link between laboratory results and in-situ behavior (Lumbroso et al. 2020).

Ring shear tests assess large-strain behavior and yield realistic estimates of residual strength after liquefaction (Macedo et al., 2022; Lumbroso et al., 2020). They replicate continuous shearing conditions similar to those in actual runouts, thereby enhancing the calibration of numerical models. Direct simple shear (DSS) tests provide additional insight into stress paths dominated by horizontal shear, which is common in layered tailings, helping link laboratory results with in-situ behavior (Lumbroso et al., 2020).

Figure 6 shows the typical mechanical responses of mine tailings under undrained monotonic loading, comparing results from triaxial compression, direct simple shear (DSS), and ring shear tests. The stress–strain curves (left) and pore-pressure response (right) illustrate peak strength, post-peak softening, and the approach to the steady-state line. (ε = axial strain).

Figure 6. Conceptual stress–strain and pore-pressure responses for triaxial, DSS, and ring-shear tests on tailings under undrained conditions, illustrating the approach to the steady-state line (adapted from Verdugo, 2024; Simms et al., 2025; Jefferies & Been 2015; Zhu et al., 2025)

Each test type reveals a distinct aspect of the stress–strain–pore-pressure relationship that influences static liquefaction susceptibility.

The triaxial test reveals a clear peak in deviatoric stress, followed by rapid softening and a quick rise in excess pore pressure. This indicates typical contractive behavior, with effective stress falling sharply at the critical state.

The direct simple shear test produces smoother stress–strain curves and a moderate increase in pore pressure, indicating horizontal shear deformation typical of layered tailings under operational loads.

The ring shear test demonstrates large-strain behavior and the shift to a stable residual strength, highlighting the post-liquefaction steady-state phase, which is essential for predicting runout and mobility.

The comparative analysis demonstrates how different laboratory techniques collectively uncover the entire deformation process, ranging from pre-failure compaction to the steady state after liquefaction.

4.2. Integration into design frameworks:

By combining triaxial and ring shear data, engineers can determine the upper and lower limits of shear strength, improving the precision of numerical and probabilistic stability evaluations. This approach aligns with the GISTM (Clarkson & Williams, 2021; Yang et al., 2022), which mandates evidence-based laboratory data for critical facilities.

In conclusion, Figure 6 shows that combining triaxial, DSS, and ring shear techniques provides a thorough understanding of tailings’ undrained behavior, linking lab data with realworld liquefaction processes and enabling safer, data-driven dam design.

4.3. Strength Parameters and Steady-State Behavior

Generating steady-state curves is crucial for differentiating stable from unstable behaviors. Ayala et al. (2023c) noted that gold tailings tend to contract considerably and have low steady-state strength. In contrast, Ji et al. (2024) and Barros et al. (2024) identified two regimes in iron ore tailings: fines contract, while coarse particles exhibit partial dilatancy. Zhang et al. (2023) and Wang et al. (2025) confirmed that higher fines content reduces permeability, accelerates pore pressure accumulation, and lowers SSL, thereby increasing liquefaction risk. On the other hand, coarser or well-drained materials are more likely to be dilative, potentially delaying failure.

Figure 7 illustrates the steady-state shear strength behavior of gold, iron, and copper tailings derived from undrained monotonic tests. The Y-axis displays the steady-state strength ratio (τ/σ′), while the X-axis indicates the axial strain (ε).

Figure 7. Steady-state strength ratio (τ/σ′) versus axial strain for gold, iron, and copper tailings, showing the effect of fines content on peak and residual strength. Adapted from (Jefferies & Been 2015; Wang et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023)

Each curve depicts the shift from peak shear stress to residual steady state, highlighting the material’s strain softening and potential for static liquefaction. Gold tailings (solid line) have the lowest residual strength, indicating rapid weakening; Iron ore tailings (dashed line) show moderate performance with partial dilatancy, affected by their bi-modal textured structure; Copper tailings (thin solid line) demonstrate moderate strain softening and retain slightly higher residual strength thanks to coarser fractions.

The downward shift of the Steady-State Line (SSL) as fines content increases (arrow) highlights the influence of microstructural composition and drainage characteristics on liquefaction potential.

Critical Analysis:

This figure provides numerical evidence on how fines content and gradation influence liquefaction susceptibility.

Fines-driven permeability regulation: As fines become more prevalent, pore pressure dissipation slows, reducing effective stress and decreasing SSL. This observation aligns with findings by Zhang et al. (2023) and Wang et al. (2025), suggesting that hydraulic constraints promote contractive behavior in fine-grained tailings.

Material-specific steady-state regimes: Gold tailings, rich in silt and clay minerals, generally collapse entirely upon reaching the critical state. In contrast, iron tailings exhibit dual behavior due to their bimodal grain-size distribution (Barros et al. 2024). Copper tailings possess residual strength slightly above that of gold tailings but still fall within the critical liquefaction range (Macedo et al., 2022).

Design implications: The SSL position is vital for stability and runout analysis. A lower SSL suggests that moderate stress increases or small phreatic rises could initiate runaway porepressure feedback, resulting in static liquefaction (ICMM et al., 2020; ICMM 2025).

Future experimental focus: Combine steady-state curves with CPTu-derived state parameters (ψ) to create predictive models linking laboratory data to field stability assessments, following the CSSM framework from Been and Jefferies (1985).

4.4. Experimental Results by Material Type

Table 2 shows representative steady-state strength ratios (τ/σ′) and residual strengths from laboratory tests on different mine tailings—specifically gold, iron, and copper. These values were obtained from recent studies involving monotonic triaxial and ring-shear experiments (Been & Jefferies 1985; Macedo et al., 2022; Riveros et al., 2023; Verdugo, 2021).

Table 2. Typical steady-state strength ratios (Su/σ′v₀) and characteristic post-liquefaction behaviors for selected metallic tailings (adapted from Verdugo 2024; Wang et al. 2024, 2025; Zhao et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023; Simms et al., 2025)

Gold tailings typically exhibit the lowest steady-state strength ratios, often below 0.1, indicating a high likelihood of contractive behavior and flow failure. Iron-ore tailings have intermediate ratios that are significantly influenced by fines content and the presence of bimodal particle distributions. Copper tailings demonstrate a range of behaviors from moderately dilative to highly contractive, depending on silt content and the degree of depositional compaction. These insights underscore the need to incorporate steady-state strength envelopes into numerical stability analyses and into strain-rate-dependent models, such as MPM or FEM, to adequately capture the gradual softening of tailings materials under stress (Ming et al., 2022).

In summary, Table 2 indicates that the steady-state strength ratio (τ/σ′) is the most reliable indicator for assessing static liquefaction risk. It links laboratory findings with the CSSM framework, offering a better understanding of field performance in tailings storage facilities.

4.5. Practical Implications for TSF Design

The design of tailings dams heavily relies on laboratory-derived parameters, which are essential for stability analysis, particularly during increases in phreatic levels or operational disturbances (ICMM et al., 2020). Accurate shear-strength envelopes and post-liquefaction data are vital for numerical modeling methods such as finite element and Material Point Method (MPM) simulations, enabling a precise depiction of failure progression and runout (Been & Jefferies, 1985). Additionally, regulatory frameworks such as the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) (Clarkson & Williams, 2021) mandate sitespecific, evidence-based laboratory testing to ensure reliable risk assessments.

Figure 8 provides a conceptual overview of how mechanical parameters obtained from laboratory tests are integrated into advanced numerical models, which, in turn, inform regulatory decision-making processes. The process begins with laboratory tests, such as monotonic triaxial, ring shear, and direct simple shear (DSS), to establish the steady-state strength ratio (τ/σ’) and the residual strength envelopes under undrained conditions.

Figure 8. Conceptual workflow for CPTu-based estimation of the state parameter (ψ), integrating partial drainage correction, uncertainty quantification, and regulatory compliance pathways (adapted from Ayala et al. 2023a–c; Reid, 2022; Robertson, 2021)

The combined evidence indicates that static liquefaction results from the gradual interaction among microstructure, drainage, and loading history, rather than from a single factor. Laboratory studies show that fines primarily reduce permeability and encourage pore pressure buildup. The depositional structure, particularly layered fabrics, facilitates localized initiation of failure. Furthermore, creep and hydrogeological feedback align with field observations, as seen in the Brumadinho failure (Krishnan et al. 2025).

Future studies should conduct multi-scale experiments, including micro-CT imaging, triaxial testing, and numerical coupling. These approaches will facilitate the measurement of fabric development during undrained shearing, allowing laboratory findings to be integrated into probabilistic liquefaction risk models.

5. In Situ Methods and Correlations (CPTu–ψ Framework)

5.1. Role of Field Testing in Liquefaction Evaluation

Field methods using cone penetration tests with pore-pressure measurement (CPTu) are now essential for assessing static liquefaction risk in mine tailings. They provide ongoing stratigraphic and mechanical profiles and enable the calculation of the state parameter (ψ), showing how close the material is to its critical state. Since 2021, multiple improvements have advanced the interpretation of CPTu data in tailings geomechanics.

An updated case history framework connects CPT behavior with susceptibility to flow liquefaction and the strength of liquefied sandy and clayey materials (Ma et al., 2025). It also enhances ψ-estimation methods for detailed, low-permeability tailings by using rescaling equations derived from calibration-chamber and numerical cavity-expansion studies (Jefferies & Been, 2019; Ayala et al., 2023a; Ayala et al., 2023b; Shuttle & Jefferies, 2023). Additionally, it explicitly considers partial drainage conditions during tailings penetration by applying a unified approach to assess system characteristics under intermediate drainage regimes accurately (Ayala et al., 2023b; Ayala, Fourie & Reid 2024; Shuttle and Jefferies 2023).

5.2. CPTu–ψ Relationships and Flow Liquefaction Screening

Robertson’s (2021) framework, as outlined by Ma et al. (2025), describes a straightforward two-step process: first, assessing susceptibility to differentiate materials that are prone to flow liquefaction from those only susceptible to cyclic mobility; second, estimating liquefied strength using normalized CPT parameters to determine residual undrained shear strength (Su_liq) in transitional materials.

Ayala et al. (2023a), Fourie et al. (2023), and Reid (2022) enhanced ψ estimation in silty tailings through calibration-chamber tests and cavity-expansion modeling, surpassing the accuracy of standard sand-based methods. Subsequent discussions (Marsden et al., 2024) clarified the boundary conditions necessary for applying this technique. Additionally, Ayala et al. (2023) showed how to rescale older CPT datasets to derive ψ values aligned with CSSM standards.

5.3. Liquefied Strength Relationships and Practical Design Applications

Accurately estimating the undrained strength at large strains is essential for evaluating slope stability and predicting runout distances, which show how far liquefied tailings can travel from failure initiation to their final deposit site. This depends on residual shear strength and energy-dissipating mechanisms. The 2021 update (Ma et al., 2025) introduced CPT-based correlations for liquefied strength across transitional regimes, improving earlier models that often overestimated residual strength in deposits composed of fine-grained or sensitive materials. Later discussions stressed the importance of using these revised correlations in tailings design, highlighting their usefulness for back-analyses of failures and for calibrating numerical models like FEM and MPM (Been & Jefferies, 2019; Ma et al., 2025; Gao et al., 2024;).

5.4. Limitations and Suggested Best Practices

Despite recent advances, several limitations still pose significant challenges to safe and reliable use.

Variability in CSL and ψ:

Mineralogical differences, depositional layering, and aging effects can shift the positions of the Critical and Steady-State Lines, potentially biasing ψ estimates if calibrated only on clean sands. Whenever possible, support CPT-based ψ estimates with laboratoryderived e–p′ data or site-specific CSL curves (Been & Jefferies, 1985; Chu, 1995; Verdugo & Ishihara, 1996; Thevanayagam & Mohan, 2000; Been et al., 2018; Qi et al., 2022).

Bonding and structure effects:

Fragile cementation may artificially increase CPT tip resistance, hiding the actual liquefaction risk. Conduct destructuration or microstructure tests to identify if bonding affects the perceived stability (Pestana & Whittle, 1999; Coop & Atkinson, 1993; Leroueil & Vaughan, 1990; Fourie et al., 2010; Coop, 2021).

Partial drainage and fines

High-fines, low-permeability tailings often undergo intermediate drainage during penetration, potentially skewing the normalized CPT responses. To achieve consistent ψ estimation and more accurate assessments of liquefied strength, using unified correction frameworks is advisable (Jefferies & Been, 2019; Ayala et al., 2023a; Ayala et al., 2023b; Fourie et al., 2023).

Uncertainty quantification:

Variability in calibration factors, material anisotropy, and measurement noise should be explicitly accounted for in probabilistic or risk-informed analyses, consistent with the principles of GISTM (Grebby et al., 2021).

5.5. Workflow for CPTu-Driven Static Liquefaction Evaluation

Figure 9 illustrates a detailed workflow for evaluating the potential of static liquefaction in TSFs using CPTu data. It combines field measurements, laboratory calibration, and uncertainty analysis into an organized and traceable process.

Figure 9. Conceptual framework for static liquefaction assessment and mitigation, integrating laboratory testing, numerical modeling, and site-specific risk evaluation, adapted from (Simms et al., 2025; Krishnan et al., 2025; Sordo et al., 2025; Jefferies & Been, 2015

Key insights from the workflow emphasize the need to integrate field and laboratory data, consistently validate CPTu correlations with laboratory-measured strength and compressibility parameters, and prevent misclassification of silty or cemented layers (Pestana & Whittle, 1999; Been et al., 2018; Qi et al., 2022). Considering partial drainage via drainage adjustments greatly improves prediction accuracy for fine-grained, stratified tailings (Ayala et al., 2023b; Ayala, Fourie, and Reid 2024). Additionally, explicitly addressing uncertainty as a core design aspect helps ensure GISTM compliance and enables transparent communication of residual risks to regulators and stakeholders (ICMM 2020; Robertson, 2021).

6. Case Studies (2020–2025)

Between 2020 and 2025, a comprehensive review of major tailings dam failures was carried out. It incorporated recent data, advanced numerical models, and interdisciplinary evidence, such as satellite deformation monitoring (InSAR). These efforts enhanced our understanding of failure mechanisms, revealing that multiple evolving factors contribute to failures that were once thought to have a single cause (Piciullo et al., 2022).

Table 3 highlights important case studies and their significance for tailings management.

6.1. Brumadinho (2019): Analysis of Progressive Failure and Creep Behavior

The collapse of Vale’s Córrego do Feijão Dam in Brumadinho is the most extensively studied tailings disaster of the last decade. Zhu et al. (2025) showed that failure results from progressive shear localization, where a slip surface gradually extends through weak, contractive layers, leading to sudden connectivity and rapid liquefaction. Grebby et al. (2021) and Reid (2022) utilized satellite InSAR data to detect measurable deformation months before the collapse, highlighting the importance of continuous monitoring. In the debate over creep versus non-creep failure mechanisms, Zhu et al. (2024) challenged earlier claims that failure was solely caused by creep. They argued that deformation was better explained by stress redistribution and hydraulic changes than by actual viscoplastic creep. This case demonstrates that post-closure facilities can unexpectedly shift from stable to catastrophic conditions without clear triggers, stressing the importance of integrated hydrogeological management and ongoing monitoring even years after deposition.

6.2. El Descargador (1963): Drainage and Pond Management

The failure of the El Descargador tailings dam in Spain, examined using contemporary methods, established a benchmark for understanding how surface water management and internal drainage influence static liquefaction (Rodríguez-Pacheco et al., 2022; Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas, 2023). Rodríguez-Pacheco et al. (2022) identified water ponding on loose, contractive tailings layers as the primary cause of failure. The reanalysis revealed that upstream construction combined with inadequate internal drainage caused rapid increases in pore pressure, even during moderate operational changes, leading to a significant reduction in effective stress. These lessons underscore the need to manage water balance, properly build beaches, and prevent the formation of large, ponded areas in fine, unconsolidated tailings.

6.3. Copper Tailings and Oil Sands: Steady-State Envelopes

A deeper understanding of steady-state strength envelopes is essential for ensuring stability. Zhao et al. (2024) reported very low steady-state strength ratios (Su/σ′v0 < 0.1) in some copper tailings, suggesting they are highly vulnerable to flow liquefaction. For oil sands, Park et al. (2025) and Schnaid (2022) used large-ring shear tests and field piezocone data to develop updated residual-strength relationships. These incorporate high fines content and partial drainage, features common in many modern TSFs. Such insights are critical for calibrating constitutive models used in advanced simulations, particularly for facilities with diverse mineralogical and depositional conditions.

6.4. Key Lessons Learned

These case studies reveal four important lessons for managing tailings dams.

- Proper beach formation needs enough width and slope to avoid ponding on deposits that could liquefy. The lack of adequate beach development has frequently been linked to failures, including El Descargador and other historical cases (Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas, 2023; Pereira et al., 2025).

- Water Control: Internal drainage systems must be designed and maintained to ensure the phreatic surface stays well below the dam crest. An increasing water table can often cause static liquefaction (ICMM et al., 2020).

- Monitoring tailings density is essential throughout the entire facility’s life cycle. Segregation during hydraulic deposition can create loose, contractive layers that may eventually fail (Fourie et al., 2014; Jefferies & Been, 2019; Ayala et al., 2023b; Robertson, 2021).

- Early Warning Systems continuously gather data from InSAR, piezometers, and visual inspections to provide actionable insights, allowing a move from reactive to proactive management of instability signs (Reid, 2022).

Table 3 summarizes the key case studies from 2020 to 2025, highlighting their mechanisms, triggers, and lessons learned from major tailings dam failures and laboratory investigations. It links historical incidents like the 1963 El Descargador failure with recent events such as the 2019 Brumadinho disaster and ongoing research on copper and fine tailings from oil sands.

Table 3. Empirical and numerical modeling approaches for static liquefaction analysis, comparing their main applications, input parameters, and limitations (adapted from Reid 2022; Rodríguez-Pacheco et al. 2022; Fourie et al. 2024)

Reanalyses suggest that failures of tailings dams rarely result from a single cause. Instead, they usually arise from a combination of factors, including hydraulic conditions, depositional history, and changing processes over time. These case studies highlight the critical role of thorough risk management across TSF’s entire lifespan, as monitoring, modeling, and operational decisions evolve collaboratively over time.

6.5. Synthesis and Broader Implications

In every case, a consistent pattern is evident: tailings dam failures seldom result from a single cause. Instead, they arise from a mix of hydraulic, structural, and mechanical factors that slowly weaken stability.

The Brumadinho incident demonstrates that routine monitoring can detect early warning signs (Morgenstern et al., 2022; Robertson, 2021). Historical cases such as El Descargador underscore the importance of managing water and drainage continuously (Rodríguez-Pacheco et al., 2022; Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas, 2023). Furthermore, research on copper and oil sands applies these insights to current facilities, highlighting the necessity of mechanical calibration and regular adjustments in risk management (Qi et al., 2022; Jefferies & Been, 2019; Fourie et al., 2024). Collectively, these case studies advocate for a comprehensive life-cycle approach to tailings management, ensuring that design, monitoring, and closure are interconnected to promote safety and sustainability over time

Figure 10 presents four key case studies—Brumadinho (2019), El Descargador (1963), Copper Tailings (2023), and Oil Sands (2024)—to illustrate different yet related mechanisms of static liquefaction across various depositional and operational contexts. Each case is organized into three sections (Causes → Mechanisms → Lessons Learned), highlighting the interplay between physical triggers, hydro-mechanical responses, and governance measures in real-world tailings storage facilities.

Figure 10. Integrated framework for static liquefaction assessment and monitoring in tailings storage facilities, covering site characterization, CPTu– ψ workflow, hydrogeological control, back-analysis, and governance (adapted from ICMM 2020, 2021, 2025; Ayala et al. 2023a–c; Jefferies & Been, 2015; Reid, 2022; Sreekumar et al., 2024)

This layout illustrates that static liquefaction rarely results from a single cause; rather, it arises from a combination of hydraulic, structural, and operational factors that accumulate over time. The use of modern data sources—such as InSAR monitoring, ring-shear testing, and hydrogeological modeling—has enabled a reexamination of past and recent failures, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their development.

Analytical commentary

Brumadinho (2019) demonstrates that shear localization progressively develops in weak, contractive layers when they are highly saturated. Recent studies (such as Zhu et al. and Grebby et al.; Reid 2022) indicate that creep-like deformation is caused by stress redistribution and hydraulic weakening rather than traditional viscoplastic flow. The key takeaway is the crucial need for continuous post-closure monitoring and integrated hydrogeological management.

El Descargador (1963) illustrates how surface ponding and inadequate drainage can lead to liquefaction in loose upstream deposits. Its reanalysis emphasizes the continued significance of water-balance and pond-control strategies, which remain crucial for legacy dams with limited drainage capacity.

Copper tailings (2023) highlight how fines and partial drainage influence strain-softening and reduce steady-state strength. Residual strength ratios (Su/σ′v₀ < 0.1) indicate a significant risk of flow failure, underscoring the need for site-specific calibration of constitutive parameters rather than reliance on empirical correlations.

The 2024 Oil Sands case studies broaden the framework by incorporating stratified deposits with high fines. Data from large-ring shear and piezocone tests reveal steady-state envelope failure under undrained conditions. This illustrates how integrating laboratory and field calibration enhances predictive models and aids in closure planning.

Critical interpretation

This synthesis emphasizes the interconnectedness of the mechanical pathways that lead to static liquefaction. It includes hydraulic triggers, such as phreatic rise and ponding, as well as microstructural factors, such as fines content and cementation. The main lessons highlight four management priorities: maintaining proper drainage and pond management; ongoing monitoring of deformation and pore pressure; calibrating constitutive models with data from laboratory and field studies; and applying these insights within governance frameworks like GISTM and ANM 95/2022.

Ultimately, Figure 10 illustrates the evolution of the field from 2020 to 2025, shifting from an event-oriented focus on failure attribution to a holistic, data-driven approach to tailings liquefaction. This change facilitates proactive, preventive management throughout the entire TSF lifecycle.

7. Guidelines, Standards, and Governance (2020–2025)

Between 2020 and 2025, TSF regulations saw major updates at both national and international levels. After catastrophic events such as Brumadinho (2019), the industry transitioned from merely strict safety regulations to adopting strategies centered on risk management, performance, and lifecycle oversight.

This section reviews the main international and Brazilian standards shaping the field, highlighting their key provisions, recent changes, and their influence on liquefaction assessment and tailings facility governance.

7.1. Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM, 2020)

Launched in 2020 by the ICMM UNEP, and PRI, the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) sets 77 requirements across six operational areas for all tailings storage facilities worldwide, both existing and new. Its purpose is to unify governance, reduce disaster risks, and improve accountability at the corporate, technical, and community levels (ICMM 2020; Owen and Kemp, 2022; Robertson 2021).

Key pillars of the GISTM include:

- Facility Engineer (RTFE) with clearly defined accountability at the corporate level, as outlined by ICMM UNEP, and PRI 2020; Owen and Kemp 2022.

- Community and environmental protection require actively involving affected populations and openly communicating potential risks (Owen and Kemp, 2022).

- Water and tailings management involve monitoring water balance, seepage, and beach formation as essential strategies to prevent liquefaction (ICMM 2020; Robertson 2021).

- Monitoring and early warning systems consist of combining InSAR, piezometric data, and automated tools to identify deformation precursors (Robertson 2021; Azam and Li, 2019).

- Emergency preparedness and response involve implementing TARPs (Trigger Action Response Plans) and detailed evacuation procedures for downstream communities (ICMM 2020; Owen and Kemp, 2022).

The GISTM focuses on performance, allowing operators flexibility to fulfill each requirement. It also underscores continuous improvements and evaluations conducted by independent third parties.

7.2. ICMM Good Practice Guide (2021, 2025 Update)

Management was first released in 2021 and was updated in 2025 (ICMM 2021; ICMM 2025).

This guide provides practical, technical steps to implement GISTM requirements, focusing on: operational controls like planning deposition, managing segregation, and monitoring hydrogeological conditions; integrating data by combining field monitoring, lab results, and numerical models to enhance decision-making; managing closure and post-closure to ensure long-term stability, especially for upstream dams and facilities in earthquake-prone zones; and establishing governance mechanisms that clearly define roles, responsibilities, and training needs for operators, regulators, and independent reviewers.

The 2025 update expands the selection of digital transformation tools, incorporating remote sensing and artificial intelligence to enhance early warning systems and facilitate real-time decision-making.

7.3. Brazilian Regulatory Framework: ANM Resolution No. 95/2022

After the Brumadinho disaster, Brazil’s Agência Nacional de Mineração (ANM) issued Resolution No. 95/2022 to revise national laws, ensuring they align with international standards and address local socio-environmental concerns (Consoli et al. 2024).

Key provisions explicitly mandate conducting a stability analysis under static liquefaction scenarios in mandatory dam safety evaluations. This framework reflects Brazil’s advancement in fostering a risk-based regulatory approach by combining international oversight standards with regional modifications to address issues like upstream dam legacies and limited regulatory capacity (Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas 2023; Agência Nacional de Mineração 2022; Robertson 2021; Owen and Kemp 2022).

7.4. Implications for Hypothetical Breach Studies

Both the Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management (GISTM) and ANM Resolution No. 95/2022 require hypothetical breach studies that specifically analyze liquefaction as a potential failure mode (ICMM 2020; Agência Nacional de Mineração, 2022; Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas 2023; Robertson 2021).

- This process uses numerical modeling techniques 5, calibrated with site-specific laboratory data.

- By combining breach modeling with subsequent consequence evaluations, these studies provide a quantitative foundation for emergency preparedness and land-use planning.

Furthermore, these studies encourage a proactive prevention strategy, advising operators to detect and address worst-case scenarios promptly, rather than responding only after failures occur.

7.5. Global Trends in Governance

Recent research emphasizes a worldwide trend toward implementing standardized governance frameworks for TSFs:

- Transparency and disclosure: Public databases like the Global Tailings Portal now provide open access to information on thousands of tailings facilities worldwide (ICMM 2020; ICMM 2021).

- Investors are increasingly assessing mining companies based on their compliance with GISTM and related environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards.

- Independent reviews are increasingly vital because they ensure third-party oversight, avoid conflicts of interest, and encourage the use of best practices (Sreekumar et al., 2024).

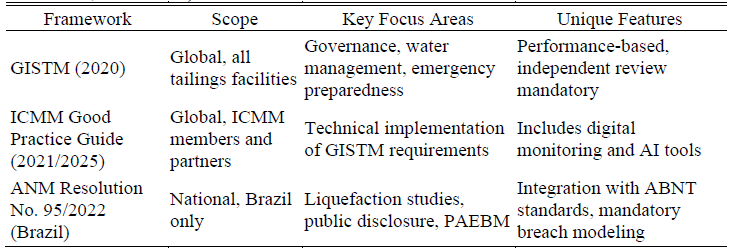

Table 4 contrasts key regulatory and governance frameworks currently shaping the management of tailings storage facilities (TSFs) worldwide.

Table 4. Comparative summary of major tailings management frameworks and regulatory instruments between 2020 and 2025 (adapted from ICMM 2020; ICMM 2021; ICMM 2025; CDA 2021; ANM 2022)

The combination of international and national frameworks marks a paradigm shift: the GISTM offers a global standard that aligns with international expectations while allowing adjustments to suit local circumstances.

- National regulations like ANM 95/2022 expand this baseline by including regional risks and practical operational factors (Barros et al, 2024; Clarkson & Williams, 2021; ICMM, 2020; Wang et al, 2020).

- The emphasis on liquefaction as a primary failure mode comes from lessons learned from catastrophic incidents such as Brumadinho and Mariana.

Challenges continue to persist, including:

- Ensuring uniform enforcement across regions with varying regulations and resources.

- Balancing transparency while safeguarding proprietary data.

- Enhancing the technical skills of regulators and operators to support the deployment of advanced monitoring and modeling systems.

7.6. Synthesis and Ongoing Challenges

The use of international standards such as GISTM and ICMM, combined with national frameworks such as ANM and ABNT, marks a significant shift in tailings governance practices.

Nonetheless, several ongoing challenges remain, including inconsistent enforcement caused by resource differences among regulatory bodies, which impacts regional uniformity; achieving a balance between data confidentiality and transparency is delicate, necessitating careful handling of public disclosures and proprietary data; building capacity requires continuous investment in technical training, understanding instrumentation, and independent audits to secure long-term compliance.

Ultimately, governance is shifting from a reactive approach focused on investigating failures after they occur to a proactive model that prioritizes early detection, accountability, and digital integration.

This transition marks one of the most important cultural changes in the global mining industry since the implementation of modern dam safety laws.

While significant advancements have been made since 2020, several essential gaps still hinder a complete understanding and effective management of static liquefaction in tailings and fine ores. These gaps include experimental methods, calibration of state parameters, predictions after site closure, integration of hydrogeological data, and the adoption of standardized monitoring practices (Clarkson & Williams, 2021; Consoli et al., 2024; Sordo et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024).

7.7. Key Gaps Identified

Representative testing for cemented/structured tailings.

Most stable or residual strength envelopes are still based on reconstituted, unbonded fabrics; the brittle collapse and destructuration in lightly cemented tailings remain poorly understood, particularly under high confining stresses and in filtered or dry-stack materials. Recent high-pressure experiments on artificially cemented iron-ore tailings demonstrate a strong dependence on porosity–cement indices and identify bond-breakage transitions that are seldom documented in design envelopes. The priority is to expand monotonic triaxial and ring-shear testing, incorporating fabric control and preloading histories that simulate field curing and aging (Ayala et al., 2023c; Barros et al., 2024; ICMM 2025).

Calibration of the state parameter (ψ) for silty/cemented matrices. New CPTu-

Rescaling based on undrained interpretations improves the accuracy of ψ estimation in tailings, but uncertainties still exist in regions with partial drainage, high fines, and bonding that affect normalization. It is recommended to perform site-specific ψ calibration by integrating CPTu dissipation data (t50) with lab-based CSL/SSL trends. Reporting ψ ranges instead of single-point estimates provides a more precise understanding (Ayala et al., 2022; Ayala et al., 2023b; Marsden et al., 2024; Monforte et al., 2023).

Post-closure criteria and “time-to-failure” forecasting.

Governance has shifted toward whole-life risk, yet quantitative post-closure criteria that link hydrogeology (phreatic rise, seepage control) to progressive liquefaction remain uneven. Priority: embed post-closure trigger windows (e.g., thresholds for phreatic elevation and deformation rate) into surveillance plans and consequence modeling.

Integration of hydrogeology–deposition–state.

Segregation and stratification produce thin, contractive layers that control slip-surface connectivity; therefore, monitoring is necessary to resolve hydrogeologic transients that move materials across the CSL. Priority: multi-evidence assimilation (piezometers + InSAR + CPTu trend maps) tied to progressive-failure models.

Minimum instrumentation and standardized back-analysis.

Instrumentation catalogs and guidance are available; however, a consistent definition of “minimum viable” arrays for different dam types—such as upstream, centerline, and dry-stack—is lacking. Back analyses continue to depend on various breach-and-runout inputs. The priorities are: (i) publish typology-specific minimum suites, including proxies for phreatic, suction, displacement, and deformation; (ii) develop standardized breach and runout databases along with reporting templates to enable easier cross-site comparison and learning (Herza & Singh, 2025).

7.8. Research and implementation priorities (actionable).

Structured material envelopes. Develop a shared dataset of steady and residual envelopes for bonded tailings (cemented, aged, and desiccated), including pre- and postbond-breakage segments and high-pressure CSLs. Report the specimen fabric, curing, and saturation protocols.

Develop workflows for tailings utilizing ψ. Establish a ψ-inference process that: (i) screens for partial drainage; (ii) performs tailings-specific rescaling; (iii) validates results against lab CSL/SSL; and (iv) generates ψ as a distribution for reliability assessment.

Post-closure surveillance criteria. Convert governance language into numeric thresholds for alarms (e.g., △head, △u, deformation rates) and connect them to TARPs and hypothetical breach updates.

Minimum instrumentation sets. For each dam class and climate: establish baseline arrays (water balance, pore pressure, deformation) with sampling rates and siting rules; include remote proxies (InSAR, ambient noise interferometry) to monitor basin-scale and near-field changes.

Standardized back-analysis & data sharing. Utilize standard parameter sets and templates from recent breach/runout compilations to ensure future back-analyses are reproducible; publish inputs/outputs when possible.

Figure 11 displays a structured, multidisciplinary checklist that consolidates best practices for assessing and managing static liquefaction in TSFs. It combines insights from recent studies and standards (Ayala et al. 2023b; CDA 2021; ICMM 2025; Reid 2022; Sordo et al. 2025; Wang et al. 2024) to connect laboratory testing, field investigations, hydrogeological monitoring, and governance compliance. The checklist is arranged into five key areas:

Figure 11. Evolution of shear zone development and slip-surface propagation leading to static liquefaction in tailings deposits, showing creep deformation and localized failure planes (adapted from Verdugo 2024; Zhu et al. 2024, 2025; Wang et al. 2024; Simms et al. 2025)

This figure links scientific understanding to real-world use. It emphasizes that effective liquefaction management depends on:

- Representative testing of real deposit fabrics, not just reconstituted ones.

- ψ-based assessments validated using site-specific CSL/SSL data.

- Quantitative thresholds for pore pressure, deformation, and phreatic rise.

- Standardized back-analysis templates ensuring reproducibility

Continuous alignment with regulatory requirements (GISTM, ANM 95/2022).

In essence, Figure 11 operationalizes the theoretical and experimental advances discussed earlier, providing a concise roadmap for field implementation and compliance with governance requirements.

8. Conclusions

Between 2020 and 2025, the scientific and regulatory landscape of static liquefaction in tailings and fine ores has advanced substantially, integrating laboratory, field, and numerical perspectives. The convergence of CSSM, state parameter (ψ) evaluation, and hydrogeotechnical monitoring has deepened our understanding of the transition from stable to liquefied states in TSFs.

Experimental research has confirmed that the content of fines, microstructure, and bonding exert first-order control on steady-state strength and residual behavior. However, laboratory testing must still evolve to accurately capture the response of structured, aged fabrics that govern field-scale behavior. Complementarily, advances in CPTu interpretation and ψ calibration have improved predictive capability, though partial drainage and cementation effects remain sources of uncertainty.

From a modeling perspective, enhanced finite element (FEM) and material point (MPM) approaches have bridged laboratory data with field-scale simulations, enabling more realistic post-failure analyses and consequence forecasting. These advances, combined with progressive failure and creep studies, have clarified that catastrophic events such as the Brumadinho disaster are rarely the result of a single mechanism, but rather of multi-stage processes involving hydraulic, structural, and mechanical feedback.

Governance frameworks—including the GISTM (2020), ICMM Good Practice Guide (2021/2025), and ANM Resolution No. 95/2022—have introduced a paradigm shift toward whole-life risk management, requiring site-specific validation, public transparency, and independent review. Nevertheless, implementation gaps persist in ensuring technical consistency, data sharing, and training across jurisdictions.

Looking ahead, the priorities for the next decade will include:

- Creating standardized datasets of bonded and aged tailings to improve steady-state and residual strength profiles.

- Formalizing ψ-based workflows that include uncertainty and partial drainage effects.

- Integrating post-closure hydrogeological monitoring into the mandatory governance cycles.

- Set minimum instrumentation standards and create uniform back-analysis procedures.

- Expanding open-access data platforms to facilitate learning from both past and current failures.

Ultimately, the industry is transitioning from empirical evaluations to predictive, performance-driven, and auditable systems that integrate physics, monitoring, and governance. This represents a significant shift in tailings geomechanics—from managing after failures occur to proactively preventing issues through data, transparency, and scientific rigor.

Author Contributions

Antonio Clareti Pereira – Conceptualization, investigation, writing (original draft and review), supervision.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

All data supporting this review can be found in the article and its references.

Permissions

The author redrew all figures and tables based on published sources cited in each caption.

References

Adria DAM, Ghahramani N, Rana NM, Kossoff D, Rico M, Martin P, Santamarina JC. 2023. Insights from the compilation and critical assessment of breach and runout characteristics from historical tailings dam failures. Mine Water and the Environment. 42(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230–023–00964–0

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). 2023. NBR 13028: Geotechnical investigations for tailings dams. Rio de Janeiro (BR): ABNT. Available from: https://www.abntcatalogo.com.br

Associação Brasileira de Normas Técnicas (ABNT). 2024. NBR 17188: Tailings facility decommissioning. Rio de Janeiro (BR): ABNT. Available from: https://www.abntcatalogo.com.br

Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO). 2021–2024. Guidelines for instrumentation and measurements for monitoring dam performance. Lexington (KY): ASDSO. Available from: https://damsafety.org/content/guidelines–instrumentation–andmeasurements–monitoring–dam–performance

Ayala J, Fourie A, Reid D. 2022. Improved cone penetration test predictions of the state parameter of loose mine tailings. Can Geotech J. 60(7):1969–1980. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2021-0460

Ayala J, Fourie A, Reid D. 2023a. Example application of the rescaling equation for CPTinferred state parameters in loose mine tailings. Int J Geomech (ASCE). 23(6):06023008. https://doi.org/10.1061/IJGNAI.GMENG–8040

Ayala J, Fourie A, Reid D. 2023b. A unified approach for the analysis of CPT partial drainage effects within a critical state soil mechanics framework in mine tailings. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering (ASCE). 149(6):04023036. https://doi.org/10.1061/JGGEFK.GTENG-10915

Ayala J, Fourie A, Reid D. 2023c. Reply to the discussion by Shuttle and Jefferies on “Improved cone penetration test predictions of the state parameter of loose mine tailings.” Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 60(7):e999–e1003. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2023-0095.

Babaki AP, et al. 2024. Numerical evaluation of static liquefaction–induced deformation in earth dams. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng (ASCE). 150(7):XXXX (a definir). https://doi.org/10.1061/JGGEFK.GTENG-11998

Barros RC, Oliveira F, Silva G. 2024. Global standards and Brazilian policies on mining tailings: the role of ANM Resolution 95/2022. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Urbana e Regional. 6(2):e4. https://doi.org/10.1590/rbeur.2024.e4

Been K, Jefferies M. 1985. A state parameter for sands. Géotechnique. 35(2):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1985.35.2.99

Canadian Dam Association (CDA). 2021. Technical bulletin: tailings dam breach analysis. Ottawa (CA): Canadian Dam Association. https://cda.ca/publications/cda–guidancedocuments/tailings–dam–breach–analysis

Clarkson L, Williams DJ. 2021. Catalogue of real-time instrumentation and monitoring techniques for tailings dams. Min Technol. 130(1):52–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/25726668.2021.1874094

Consoli NC, Carvalho JVA, Wagner AC, Bittencourt LA. 2024. Porosity and cement controlling the response of artificially cemented tailings under hydrostatic loading to high pressures. Sci Rep. 14:29309. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598–024–80937–7.

Coop MR, Atkinson JH. 1993. The mechanics of cemented carbonate sands. Géotechnique. 43(1):53–67. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1993.43.1.53.

Coop MR. 2021. Editorial. Géotechnique. 71(2):95. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.2021.71.2.95

Fourie AB, Reid D, Macedo J. 2023. The influence of hydrogeology on static liquefaction potential in mine tailings. Géotechnique. 73(4):350–365. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.21.P.123

Grebby S, Sowter A, Novellino A, Gee D, Holley R, Roberts C. 2021. Advanced analysis of satellite data reveals ground deformation precursors to tailings dam failure. Commun Earth Environ. 2:79. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247–020–00079–2

Herza J, Singh R. 2025. Risk-informed instrumentation of tailings storage facilities. In: Proceedings of Paste/TSF 2025; Perth (AU): Australian Centre for Geomechanics (ACG). https://papers.acg.uwa.edu.au/d/2555_49_Singh/49_Singh.pdf

International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM); United Nations EnvironmentProgramme (UNEP); Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). 2020. Global industry standard on tailings management (GISTM). London (UK): ICMM.https://globaltailingsreview.org

International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). 2021. Good practice guide: tailings management. 2nd ed. London (UK): International Council on Mining and Metals. https://hub.icmm.com

International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). 2025. Good practice guide: tailings management – digital transformation update. London (UK): International Council on Mining and Metals. https://hub.icmm.com.

Jefferies M, Been K. 2015. Soil liquefaction: a critical state approach. 2nd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19114

Ji X, Ma J, Liu Y, Zhang T, Chen W. 2024. Critical state analysis for iron ore tailings with a fine–coarse bi-modal structure. Water. 16(20):2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16202958

Krishnan K, Beaty M, Bray JD, Manzari MT, Liu P. 2025. Hybrid finite-element and material point method for modeling liquefaction-induced tailings dam failures. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng (ASCE). 151(10):04025095. https://doi.org/10.1061/JGGEFK.GTENG-13377.

Leroueil S, Vaughan PR. 1990. The general and congruent effects of structure in natural soils and weak rocks. Géotechnique. 40(3):467–488. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1990.40.3.467

Lumbroso D, Walker G, Purdie J, Smith K, Brown A. 2020. Modelling the Brumadinho tailings dam failure, the subsequent loss of life and how it could have been reduced. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci Discuss. 2020:1–29 (preprint). https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2020159

Macedo J, Fourie AB, Reid D, Williams DJ, Carvalho JVA. 2022. Properties of mine tailings for static liquefaction assessment. Can Geotech J. 59(5):e1–e12 (pagination per publisher). https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj–2020–0600

Ma L, Fu X, Xu Y, Chen Q, Wang Z. 2025. Spatial evolution analysis of tailings flow from dam failure using 3-D simulation. Appl Sci. 15(4):1757. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15041757

Marsden L, Grebby S, Novellino A, Sowter A, Holley R. 2024. Advances in early warning systems for tailings dam monitoring: integrating InSAR and ground-based sensors. Nat Commun. 15:4210. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467–024–4210–5

Ming L-Q, Zhang Y-B, Zhao Y-M, Li Y, Liu S. 2022. Numerical simulation on the evolution of tailings pond breach: application to rapid risk assessment. Front Earth Sci. 10:901904. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.901904

Monforte L, Arroyo M, Gens A. 2023. A relation between undrained CPTu results and the state parameter for liquefiable soils. Can Geotech J. 60(11):1493–1506. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj–2022–0377.

Owen JR, Kemp D. 2022. Mining, tailings governance, and the Global Industry Standard: critical reflections and practical pathways for implementation. Resour Policy. 78:102780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102780

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Park J, Wang K, Fourie AB, et al. 2025. Residual strength characterization of oil sands fine tailings using integrated ring shear and field CPTu data. Can Geotech J. 62(5):713–729. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj–2024–0568

Pereira AC, Fonseca RBC, Santos JR. 2025. Liquefaction of iron ore fines in maritime transport: advances, challenges and safety perspectives. Stud Eng Exact Sci. 6(2):1–30. https://doi.org/10.54021/seesv6n2–013.

Pestana NJ, Whittle AJ. 1999. Formulation of a unified constitutive model for clays and sands. Géotechnique. 49(4):471–492. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1999.49.4.471