RESSECÇÃO SEGMENTAR DE AMELOBLASTOMA EXTENSO

RESECCIÓN SEGMENTARIA DE AMELOBLASTOMA EXTENSO

REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/ma10202408301054

Main Author:

Arthur Araújo de Souza1

Authors:

Geovana Borba de Albuquerque2

Pedro Guimarães Sampaio Trajano dos Santos3

Lucas Cavalcanti de Lima Félix4

João Bezerra Lyra Neto5

Luciano Barreto Silva6

Ailton Coelho de Ataíde Filho7

Juliana Perez Leyva Ataíde8

Rodolfo Scavuzzi Carneiro Cunha9

Vinicius Balan Santos Pereira10

Abstract

Odontogenic tumors, such as ameloblastoma, are generally benign, but can behave aggressively. This case report concerns a 26-year-old male patient with multicystic ameloblastoma in his mandible, which was diagnosed after sings of facial asymmetry and enlargement. Radiographic characteristics, such as multiloculation in the form of “honeycombs” together with the use of incisional biopsy were crucial for the diagnosis. The treatment consisted in segmental resection of the tumor and reconstruction with a titanium plate. The objective of this article is to demonstrate that adequate treatment is essential due to the aggressive potential and recurrences of ameloblastoma.

Keywords: Ameloblastoma; Biopsy; Neoplasia.

Resumo

Tumores odontogênicos, como o ameloblastoma, são geralmente benignos, mas podem se comportar de forma agressiva. Este relato de caso diz respeito a um paciente masculino de 26 anos com ameloblastoma multicístico em mandíbula, diagnosticado após sinais de assimetria e aumento facial. Características radiográficas, como a multiloculação em forma de “favos de mel” juntamente com o uso de biópsia incisional foram cruciais para o diagnóstico. O tratamento consistiu em ressecção segmentar do tumor e reconstrução com placa de titânio. O objetivo deste artigo é demonstrar que o tratamento adequado é essencial devido ao potencial agressivo e às recidivas do ameloblastoma.

Palavras-chave: Ameloblastoma; Biópsia; Neoplasia.

Resumen

Los tumores odontogénicos, como el ameloblastoma, son generalmente benignos, pero pueden comportarse de manera agresiva. Este reporte de caso se refiere a un paciente masculino de 26 años con ameloblastoma multiquístico en su mandíbula, que fue diagnosticado después de signos de asimetría facial y agrandamiento. Las características radiográficas, como la multiloculación en forma de “panal de abejas” junto con el uso de biopsia incisional fueron cruciales para el diagnóstico. El tratamiento consistió en la resección segmentaria del tumor y reconstrucción con una placa de titanio. El objetivo de este artículo es demostrar que el tratamiento adecuado es esencial debido al potencial agresivo y las recurrencias del ameloblastoma.

Palabras clave: Ameloblastoma; Biopsia; Neoplasia.

Introduction

Odontogenic tumors can be categorized as neoplasms that are generally benign and related to the proliferation of cells directly involved in odontogenesis and the Epithelial Rests of Malassez. They are subdivided according to the histological pattern that originated them, and are then classified as epithelial, mesodermal and mixed1. Within this clinical universe, and even though they are of benign epithelial origin, ameloblastomas behave clinically aggressively and account for around 10% of odontogenic tumors2. This type of neoplasm is most commonly associated with the mandible (80%) and less frequently with the maxilla (20%)1,2. However, its imaging characteristics resemble other mandibular lesions of odontogenic and non-odontogenic origin. The precise diagnosis and appropriate form of treatment are determined by histological examination, but clinical findings and imaging studies, through panoramic radiographs and computed tomography (CT), present some important characteristics for narrowing the differential diagnosis. It’s typical multiloculation in a “honeycomb” shape provides the radiologist with enough information to determine its diagnosis, suggesting almost immediately its identification and forms of treatment. The objective of this study was to report the case of a male patient, twenty-six years of age, with an initial diagnosis of multicystic ameloblastoma, and the way in which the tumor was treated.

Case Report

A twenty-six-year-old male patient with no history of systemic comorbidities and no alcohol or smoking habits sought treatment at the Hospital de Fraturas do Recife – PE due to facial asymmetry and significant volume increase after painful symptoms during chewing. At the time of consultation, he reported no pain, only discomfort when eating and aesthetic implications (Figure 1)

Fig. 1. Frontal and lateral view of the patient. Marked asymmetry and mandibular bulging resulting from centrifugal expansion of the tumor can be observed.

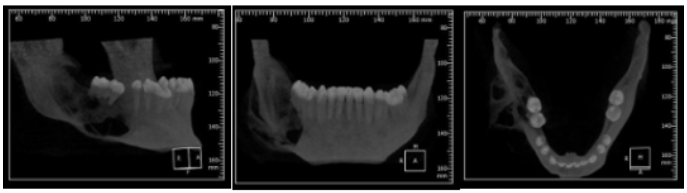

Internally, an increase in volume could be observed with greater involvement of the vestibular portion, with displacement and root resorption of the dental elements and impossibility of chewing in the area. Therefore, a computed tomography scan was requested for better visualization of the lesion (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Lateral, frontal and occlusal view of the mandible in computed tomography. In the chin region, involvement of the body and horizontal ramus of the mandible can be observed, where a lytic, insufflative lesion with a classic multiloculated appearance compatible with classic ameloblastoma is seen.

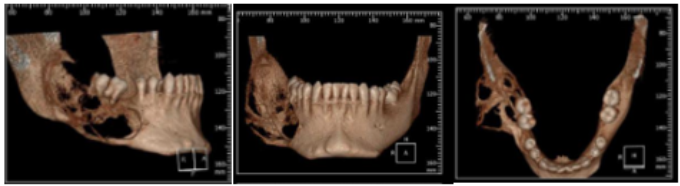

The 3D reconstruction images show an expansive lesion with extensive bone destruction, multilocular with poorly defined margins and multiple regions of vestibular and lingual cortical bone fenestration affecting the mandibular body and part of the ascending ramus (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. Lateral, frontal and occlusal view of the mandible in 3D tomographic reconstruction.

After the initial procedures of aspiration puncture of the tumor content to eliminate the possibility of a lesion with vascular involvement and aid in the diagnosis, an incisional biopsy was performed which came with the histopathological diagnosis of Solid Ameloblastoma. After conclusive diagnosis of the lesion, a stereolithographic model of the mandible was requested where the cutting guide was made for segmental resection and modeling of the 2.7 reconstruction plate of the lock system. With the planning finalized, the patient proceeded to the surgical block for segmental resection of the tumor and load-bearing fixation with a titanium plate.

Fig. 4. Patient sedated before undergoing hemimandibulectomy for en bloc resection of the tumor and placement of the titanium plate.

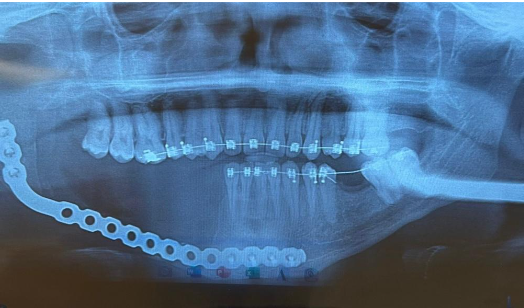

The surgical field was asepsised with 2% Chlorhexidine solution, with the surgical fields apposed and an oropharyngeal tampon installed. The right submandibular incision was then drawn, extending to the submental region with brilliant green, and the supraplatysmal region was infiltrated with 0.5% Bupivacaine Hydrochloride + Epinephrine 1:200,000. An incision was made in the skin with a cold scalpel and the deep layers were divided into planes with the aid of an electric scalpel up to the mandible, after exposing the tumor and releasing the portion of soft tissue that surrounded the lesion, taking care not to leave any tumor remnants. An osteotomy was then performed for resection with Piezo in the proximal portion due to the proximity to noble anatomical structures in the region and with a reciprocating saw, and then the lesion was removed with a safety margin indicated for benign tumors. During the resection, care was taken to preserve the facial vascular structures for subsequent reconstruction with a microvascularized fibular graft and subsequent installation of dental implants and full rehabilitation of the patient, with the aim of restoring aesthetics and function as a result of surgery to treat a locally aggressive pathology. The plate was then positioned, which had been previously modeled and outlined in a 3D model to reduce surgical time and facilitate its positioning in the remaining right mandibular body and in the portion of the ascending ramus. After the fixation was completed, intraoral and deep plane sutures were performed with Vycril 4.0 and skin sutures with Nylon 5.0. Immediately after the suture was completed, the patient’s face already demonstrated better symmetry and a normal appearance (Figure 5). The patient continued to be monitored as an outpatient and after the suture was removed, a quarterly follow-up was performed for reassessment, and a panoramic radiograph was performed 1 year postoperatively (Figure 6).

Fig. 5. Removal of the ameloblastoma and facial appearance of the patient immediately after the procedure.

Fig. 6. Panoramic radiograph 1 year after surgery.

Discussion

From a clinical point of view, ameloblastomas are slow growing and are often found in the mandible or maxilla. Symptoms are minimal and are rarely noticed by the patient in the early stages, sometimes being diagnosed during routine radiographic examinations. In the patient in question, we saw that his case could have had a more conservative outcome, since he had previously sought medical care at a local clinic and had been diagnosed with lipoma, and consequently did not give due importance to the problem.

The etiology of ameloblastomas is related to the remains of dental lamina in the development of the enamel organ, basal cells of the oral mucosa or associated with an impacted tooth. Its relationship with REM has also been described4. It was quite clear in this clinical case that the absence of pain and information, associated with the slow growth of the tumor, hinder the treatment of this clinical entity; Unfortunately, this clinical behavior, associated with its slow and asymptomatic growth, led to displacement of the remaining teeth and consequent mobility and tooth resorption, as well as paresthesia and displacement of the remaining teeth.

The clinical implications of an ameloblastoma are generally dramatic when detected late. They are classified into three types: solid or multicystic, which is the most common form with radiographic characteristics of a multilocular appearance; unicystic, presenting radiographic characteristics of a unilocular appearance with cystic and well-defined characteristics, generally affecting younger patients; and the extraosseous or peripheral type, which is the soft tissue repercussion of this type of lesion. In this specific case, we had the classic “honeycomb” arrangement, facilitating diagnosis. Its centrifugal growth caused by pressure most of the time results in root resorption and major bone destruction as a direct consequence.

Ameloblastoma is an odontogenic neoplasm that accounts for approximately 1% of all oral neoplasms3, and is a tumor originating from the various layers of the odontogenic epithelium, including the follicular epithelium of the teeth. It usually manifests between the third and fifth decades of life, but there are also reports of involvement in patients of other age groups1,2. Its incidence among men and women is similar, with few statistical differences. It presents clinically as a slow-growing mass, which may or may not be painful1. The overwhelming majority of ameloblastomas affect the rami and posterior body of the mandible, but larger tumors may infiltrate adjacent soft tissues, usually resulting from areas of rupture of the cortical bone on the lingual surface of the mandible2, as we observed in the case in question.

Ameloblastoma was cited as the most aggressive of the odontogenic tumors, due to root resorption, large bulges and high potential for recurrence5. Their radiological aspects, however, may vary in some situations. Some present as well-defined unilocular radiolucent lesions, with or without marginal sclerosis, which are frequently associated with an impacted tooth; others present with a multilocular aspect, with internal septa and a “honeycomb” or “soap bubble” pattern. The loculations may be oval or rounded and vary in size. Ameloblastomas are characteristically centrifugally expanding tumors, which may present poorly defined margins and consequent perforation of the bone cortex, which facilitates invasion of the surrounding soft tissues and involvement of adjacent nerves, facilitating loss of sensitivity. CT aspects include hypodense cystic areas associated with areas of greater attenuation representing solid portions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may, in some cases, even demonstrate more clearly the extent and expansive limits of the lesion; It is important to note that both CT and MRI assist in therapeutic management, showing the tumor outline in detail1,2.

The behavior of ameloblastoma tends to be quite aggressive in recurrences, with greater potential for invasion and bone destruction than the original lesion6 . Thus, in some situations the surgeon may decide to remove the tumor with a safety margin. The differential diagnosis is made with odontogenic keratocysts and dentigerous cysts. Traumatic bone cysts are also included in this list7. It should also be taken into account that local aggressiveness and recurrences may have aspects similar to those of malignant neoplasms, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma should also be considered as a differential diagnosis2.

Conclusion

Thus, the present study demonstrates the importance of a correct diagnosis based on clinical and imaging examinations. Segmental resection proved to be the most effective technique in the treatment and in preventing recurrence of the lesion, despite the mutilating aspect of the treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Som PM, Bergeron RT. Head and neck imaging. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book, 1991.

2. Scholl RJ, Kellett HM, Neumann DP, Lurie AG. Cysts and cystic lesions of the mandible: clinical and radiologic-histopathologic review. RadioGraphics 1999;19:1107-24.

3. Bataineh AB. Effect of preservation of the interior and posterior borders on recurrence of ameloblastomas of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;90:155-63.

4.Neville,B.W.et al.Patologia oral e maxillofacial.2.ed.Rio de Janeiro:Guanabara Koogan,2004.

5.Alvares LC, Tavano O. Curso de radiologia em odontologia. 4ª ed. São Paulo, SP: Livraria Editora Santos, 1998.

6.Rosenstein T, Pogrel MA, Smith RA, Regezi JA. Cystic ameloblastoma: behavior and treatment of 21 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;59:1311-6.

7.Laskin DM, Giglio JA, Ferrer-Nuin LF. Multilocular lesion in the body of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;60:1045-8.

1ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4315-4304

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: arthuraraujo2612@gmail.com

2ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9962-9420

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: geovanaborba311@gmail.com

3ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5720-603X

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: pedroguimaraessampaio@gmail.com

4ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7677-591X

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: lucascavalcanti209@gmail.com

5ORCID:https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6044-0313

Faculdade Pernambucana de Saúde, Brazil

E-mail: itsjoaolyra@gmail.com

6ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1508-4812

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: lucianobarreto63@gmail.com

7ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8105-4259

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: ailtonataide@hotmail.com

8ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3673-7651

Universidade de Pernambuco, Brazil

E-mail: juliana.ataide@upe.br

9ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-848X

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: scavuzzi@gmail.com

10ORCID:https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4311-1766

Faculdade de Odontologia do Recife, Brazil

E-mail: viniciusbalan99@gmail.com