REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8400962

Marisa Resende Parreira[1]

Paulo Henrique da Cruz Ferreira[2]

Liliany Mara Silva Carvalho[3]

George Sobrinho Silva[4]

Guilherme Nogueira Mendes de Oliveira[5]

Antônio Moacir de Jesus Lima[6]

Abstract

The Psychosocial Care Network (PCN) is an indispensable network of care within the healthcare network (HCN) that aims to create, expand, and interconnect points of health attention for individuals experiencing mental suffering or disorders as well as the need for crack, cocaine, alcohol, and other substances. The functioning of this network relies on coordination among diverse services. This study aimed to analyze PCN and its functionality in the municipality of Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. A qualitative research approach was employed utilizing Oral History as a methodological resource. The coordinators and/or collaborating members of the PCN pact within the municipality were interviewed. Data collection was centered around the guiding question: “Please elaborate on how your service collaborates with other network services in providing assistance to mental health users?” The collected data were transcribed and used for content analysis, leading to the identification of the three thematic axes. These findings enabled the identification of factors conducive to the consolidation of the PCN, as well as its primary challenges. The construction of networks has emerged as a complex endeavor, necessitating cohesive actions in conjunction with other services and stakeholders for solidification. It was also apparent that a fundamental aspect of ensuring comprehensive care lies in the understanding of the objectives and functionalities of the professionals within this network, underscoring the need for the resurgence of matrix support and a municipal mental health manager engaged in public policies, coordination, planning, and monitoring of activities. Thus, through interdisciplinary engagement, the Psychosocial Care Network fortifies its presence, building upon its existing foundation.

Keywords: Healthcare network. Mental Health Assistance. Health Care Levels. Collective Health.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the 1990s, the propositions of Psychiatric Reform began to be integrated into the guidelines of public health policy. The democratization of the country and the establishment of the Unified Health System (SUS) during the 1988 Constitution and its regulation in 1990 allowed the Psychiatric Reform to develop its proposal to replace the hospital-centered model with a community-based psychosocial care network on more institutional grounds (KINKER; BARREIROS, 2014).

The Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) were among the first services introduced by the National Mental Health Policy as replacements for the asylum model. These open and community-based health services consist of a multidisciplinary team that operates from an interdisciplinary perspective, primarily attending to individuals with mental distress or disorders, including those with needs stemming from the use of crack cocaine, alcohol, and other substances, within their territorial scope, whether in crisis situations or in psychosocial rehabilitation processes (BRASIL, 2011, 2015a).

To organize healthcare systems, it is most suitable to distinguish acute conditions, which often occur suddenly and can be addressed by a reactive system of episodic responses, from chronic conditions, which have a more or less prolonged course and require a proactive, continuous, and integrated response system (MENDES, 2011).

In Brazil, the healthcare system appears fragmented, reactive, episodic, and primarily oriented towards addressing acute conditions and exacerbations of chronic conditions. Consequently, it is ineffective at resolving chronic diseases. Therefore, it is imperative to restore coherence between the health situation and SUS, particularly with the implementation of healthcare networks (HCN), which represent a novel approach to organizing the healthcare system into integrated systems that can effectively, efficiently, safely, and equitably respond to the health conditions of the Brazilian population (MENDES, 2011).

At the end of 2010, as a result of a significant tripartite agreement involving the Ministry of Health, the National Council of Health Secretaries (CONASS), and the National Council of Municipal Health Secretaries (CONASEMS), Regulation No. 4,279 was issued on December 30, 2010, defining an HCN as an organizational arrangement of health actions and services with varying technological densities, integrated through technical, logistical, and managerial support systems, aiming to ensure comprehensive care (BRASIL, 2010).

The Psychosocial Care Network (RAPS) was established by Regulation No. 3,088 in 2011, and set forth the creation, expansion, and coordination of healthcare points for individuals with mental distress or disorders, along with the need for the use of crack cocaine, alcohol, and other substances. The RAPS is an integral part of the SUS, sharing its principles and directives (BRASIL, 2011). This network aims to expand access to psychosocial care for the general population and facilitate access to various care points by users and their families. To achieve these objectives, in addition to addressing emergencies, the network seeks to ensure coordinated and integrated work among care points, enhancing care through reception and continuous monitoring (BRASIL, 2011).

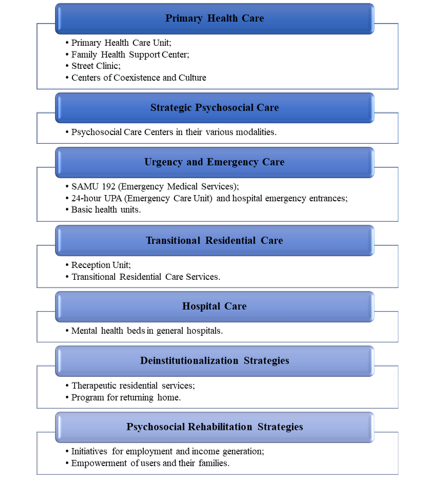

The RAPS comprises distinct services addressing diverse needs, encompassing primary health care, specialized psychosocial care, urgent and emergency care, temporary residential care, hospital care, deinstitutionalization strategies, and psychosocial rehabilitation strategies (BRASIL, 2011). Figure 1 shows the components of the RAPS and its care points.

Figure 1: Components of the psychosocial care network.

Source: Adapted from BRAZIL, 2011.

Psychiatric reform brought and continues to bring about an ongoing construction of strategies and policies to strengthen the SUS. RAPS represents one such strategy that advances towards comprehensive care for individuals with mental disorders. To this end, the participation of workers in a continuous process of implementing and enhancing the network, psychosocial rehabilitation, and empowerment of users and their families is crucial, fostering more integrated and democratic care processes (BRASIL, 2015b). The challenges to overcome in developing the propositions for psychiatric reform remain extensive, as asserted by Kinker and Barreiros (2014).

Thus, this study aims to analyze the structure of the RAPS in the municipality of Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil, its functionality, and its primary challenges, and to identify and describe aspects conducive to the consolidation of the RAPS as a reference within this network’s policies.

2. METHODOLOGY

This study employed a descriptive exploratory qualitative research approach, utilizing the thematic oral history method to analyze the functionality of the mental health network in Diamantina, based on oral accounts obtained from the target population. Thus, the study was conducted in the municipality of Diamantina, situated in the central northern region of Minas Gerais, Alto Vale do Jequitinhonha, Brazil.

The research participants were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: being a service coordinator for a period of one year or more, expressing a desire to participate in the study, and committing to schedule data collection in collaboration with the researcher. The exclusion criteria included a lack of desire to participate and the absence or nonexistence of coordination within the sector.

As Turato (2008) asserts, sample determination should prioritize the potential to deepen and broaden the understanding of the social group rather than a numeric representation that would lead to the generalization of results. Thus, interviews were conducted with coordinators and/or collaborators of services directly engaged in mental health care. These individuals were selected because of their direct involvement in providing comprehensive and coordinated care to users and their support network. This approach aimed to discern the research subjects in a unique manner, thus enhancing the reliability of comprehending the study’s object.

The diverse care points were represented by their respective coordinators and/or collaborators, in accordance with the current composition of the RAPS, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1: List of services/coordinators/collaborators who participated in interviews organized according to the current scenario of the RAPS in Diamantina, MG.

Components of the RAPS RAPS in Diamantina/MG Services Function Primary Health Care Urban UBS/ESF: 08; Rural UBS/ESF: 03; NASF: Not available; Street Clinic: Not available; Center of Coexistence and Culture: Not available. Primary Health Care Coordinator Strategic Psychosocial Care CAPS II – Mental disorders; CAPS-AD (Alcohol/drugs); Both for users above 18 years. Mental Health CAPS CAPS-AD Psychologist, Nurse, and Social Worker Urgency and Emergency Care SAMU 192; Emergency Care SCCD; Emergency Care HNSS; Fire Department. HNSS Emergency Care; Fire Department Social Worker Commander Transitional Residential Care No agreement Not performed Not performed Hospital Care 05 mental health beds at SCCD HNSS Deinstitutionalization Strategies 02 users enrolled in the Program for Returning Home Not performed Not performed Psychosocial Rehabilitation Strategies Association of users Not performed Not performed

HNSS: Hospital Nossa Senhora da Saúde de Diamantina, MG, Brazil. SCCD: Santa Casa de Caridade de Diamantina, MG, Brazil.

2.1 Study limitations

This study had certain limitations. Initially, due to the post-electoral period, a change in the cadre of managers and coordinators within some network points transpired, resulting in the rescheduling of some data collection sessions originally aligned with the timeline. It is noteworthy that operational issues led to the unavailability of data collection at the Emergency Care Unit, SAMU, Association of Mental Health Users, and Specialized Reference Center for Social Assistance (CREAS).

Furthermore, the Center for Psychosocial Care (CISAJE) was included as a network component given its role in conducting psychiatric outpatient consultations. A similar procedure was adopted for the inclusion of CREAS, representing a sector catering to a substantial number of mental-health patients. Unfortunately, technological problems attributed to cellphone malfunctions have led to the loss of audio recordings from these services, hindering transcription.

2.2 Participant engagement and data collection

Prior to data collection, personal engagement was established with psychosocial care points, involving invitations, research information, methodology, and obtaining consent for recording testimonies via cellphone voice recorders. Interviews were scheduled based on collaborator availability and conducted between May and October 2017. Before each interview, the participants were introduced to, read, and signed an Informed Consent Form (ICF) with a copy provided to the participant.

Creating conditions that fostered freedom, trust, and spontaneity was paramount to enable informants to enrich the investigation. Accordingly, conducive environments were selected to facilitate participants’ choice.

2.3 Data collection approach

Data collection revolved around the central guiding question: “Describe how the service you are affiliated with collaborates with other network services to provide mental health user assistance?” This approach enabled the participants to share their lived experiences and insights related to the investigated matter. This process facilitated the description and assessment of Diamantina Psychosocial Care Network (RAPS) functionality, identifying challenges tied to its consolidation and proposing strategies to enhance the comprehensiveness of access points.

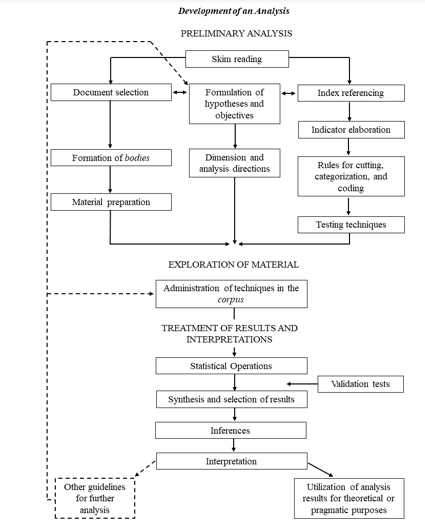

The collected data were transcribed and used for data analysis. These data were classified based on theoretical foundations, leading to the formulation of categories that encompass elements or aspects with common characteristics or interconnections. The method chosen for investigating the collected material was content analysis, as proposed by Bardin (2006). This approach comprises the following stages:1) pre-analysis; 2) material exploration; and 3) results in treatment, inference, and interpretation. Figure 2 schematically illustrates the sequence articulated by Bardin (1977).

Figure 2: Development of content analysis.

Source: Bardin (1977). Adapted.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and the Mucuri Valleys (Protocol No. 1899520). Following the synthesis period of the oral inquiry, the researcher returned to the field where authorization for partial or complete publication of the interviews was obtained, following the revision and transcription of the text, as required by the oral history method (MEIHY, 2002).

3. DATA ANALYSIS

After exhaustive listening to the recorded narratives and reading transcriptions, the utterances were segmented into text excerpts and grouped based on similarities. Consequently, possibilities of meaning emerged, forming three thematic categories.

- Network Exists, Yet Fragmented, arising from subcategories: lack of communication among services and absence of a governance system;

- Challenges in Mental Health Actions within Primary Care, resulting from absence of matrix support and inadequate screening; and

- User Reception stems from subcategories of human resource shortage and excessive user demand.

The first thematic axis was developed according to the statements reproduced when the researcher initiated the interviews, guiding the question: How does your service collaborate with other network services in providing mental health support to users? How does the user access this service? How do they arrive? How does your service interface with your network?

3.1 Network exists, yet fragmented

By fragmented networks, we refer to those organized through isolated points of healthcare attention that fail to communicate effectively among themselves, rendering them unable to provide continuous care to the population. Generally, there is no assigned population for accountability, which hinders population-based management (Mendes, 2010).

Mendes (2010) asserted that under these circumstances, primary healthcare does not smoothly communicate with secondary healthcare, which, in turn, lacks communication with tertiary healthcare or support systems. In these systems, primary care cannot fully exercise its role as a center of communication and coordinating care.

Interviewees acknowledged the network’s existence but emphasized the need for articulation, attributing the lack of communication, absence of a governance system, and regulation as contributing factors to this fragmentation. This led to the emergence of the following subcategories.

Professionals interviewed mentioned that communication between services occurs on an ad hoc basis, implying that contact is only established with the network to address emerging demands. Therefore, there is no effective and continuous interaction between various attention points.

E1: “We do not have this dialogue, right? Not even with primary care, which is an everyday thing…”. “Demand arises, we go there and make a call. Is there no consistency, right? In this partnership.” “Whenever we need something, we make a call to discuss that case; it’s an emergency…”

E3: “We have more contact when we need the service.” “And from them to us, it doesn’t exist.”

E6: “Based on need, according to the demand the patient is presenting at that moment.”

E7: “How is the Network of Psychosocial Care (RAPS) going to function when the services themselves haven’t established seamless communication? It’s sporadic! We coordinate, have private discussions with primary care about specific cases, but it’s arbitrary.”

Despite the fragmentation of this network, interviewees affirmed its existence, calling for planned and coordinated actions to strengthen it. They suggested that establishing communication protocols and a governance system could potentially integrate these disparate components.

E1: “… This was a fragmented network. We perceive that we’re working somewhat isolated, everyone is engaged in their internal demands…”. “So that we can coordinate with other services, right? Become more familiar with the structure we have, the resources available at each level of care, to have a dialogue, and to be able to receive, right? This user who will ultimately navigate through all these areas, right?”

E2: “…a network does exist, but what’s lacking is the communication within this network, it’s about creating procedures, communication strategies, structural functioning, so that we can have a more effective dialogue. But this network does exist.”

E4: “So I feel this difficulty. This need, because I do not see communication between the services, right? So, for example, if a patient is discharged… there’s no communication, no referral, no counter-referral, it does not exist! However, there is much room for improvement, creating this flow, improving referral and counter-referral, and improving communication. There’s work to be done.”

E6: “Now, what I think is lacking is a better alignment between our unit and the network. Because it’s still deficient…”

E9: “I think things need to be more publicized because, for example, we know what CRAS is for. We know what the CREAS is for. However, let us say that we start an intervention. Similar to, the folks at the GRS are. We are trying to organize these issues related mainly to the mental health network, which is quite limited in Diamantina, you know? We talk about other things, but when we realize that we have nothing to offer to mental health users, you feel lost. So, let us say, the people at GRS know the services they can offer, it is about disseminating! Not just to healthcare institutions, but to the people, so they know what exists.”

Nóbrega et al. (2016) emphasized that the challenges of expanding mental health assistance in RAPS are diverse. Dialogue among health care professionals is a key factor for effective work and must be continuously cultivated by the team. Discussing the RAPS guidelines through forums and training is essential for enhancing its expansion. Commitment, communication, and collaboration among professionals yield gains, as they overcome the challenges inherent in patient care processes.

One of the components of a healthcare network is the governance system. Governance entails a unified governance system for the entire network aimed at creating a mission, vision, and strategies for organizations within the health region; defining short-, medium-, and long-term objectives and goals; coordinating institutional policies; and developing the necessary management capacity to plan, monitor, and evaluate managers’ and organizations’ performance (BRASIL, 2010).

Discourses suggest that the absence of policies, planning, coordination, and action monitoring, possibly due to weak or absent coordinating bodies, hinders the effective communication, understanding, and establishment of this network.

E1: “We need someone responsible for expediting this process. For example, the state or a municipal representative for mental health, because then they will be there for these issues, right? We call the management to gather the network and facilitate these discussions. So, if everything remains with mental health, just like primary care has a plethora of programs, we will never sit down, never see the difficulties. If we have difficulties talking, they also struggle to listen and interact with them. It would have to start from something, perhaps a municipal representative who would know? Like the GRS, could that also be their function? I think these things need more discussion; you know?”

E7: “Create an organizational chart, get the teams together, and discuss them. I go to primary care, I go to the secretariat, go to the hospital network, and go to the CRAS. What comprises RAPS? Let us break down each point and discuss how to work together. How can we collaborate? Let us jointly create a tool that facilitates this. This, we don’t have! It doesn’t exist! RAPS hasn’t been built, and the services haven’t come together to discuss something built collectively.”

E3: “Establish guidelines and protocols right? A well-structured approach for us to put into practice.”

E6: “It does not exist. And it never existed as a technical reference for mental health… it does not exist! What we have today, in reality, is a push therapy, you know?”

E7: “Our state-level coordination, we have a local reference from the state that could help us build this; they could be a guide, a facilitator for this collaboration.”

E8: “…but it’s missing, for example, we have had several contacts with the department’s regulation to come here and say, ‘hey, guys, a patient with this condition goes to the ED, a patient with this condition and age goes to the hospital, a specific spine-related trauma goes to the ED, at the hospital it’s other issues,’ this contact, this feedback, to say who’s responsible? Who is responsible for the mental healthcare network? Who will be the CAPS? So, here comes CAPS! Could it be possible to come here and present the main regulations and the main flow used in larger centers or where there’s the Fire Department, the EMS, or another agency providing pre-hospital care?”

It is also evident that the absence of a governance system creates barriers to the movement and understanding of this network. These statements highlight that the lack of a reference complicates the workflow. They stressed the necessity of creating protocols and flow charts.

Dimenstein’s (2012) investigation, aiming to understand the configuration, operation, and modes of reception in the RAPS in Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, identified that the absence of specific protocols affects the quality of care processes. These guiding documents can induce good practices and protective factors, both in clinical practice and management and for users. Regardless of their importance and potential, protocol usage must be tied to broader concerns about work processes. They should drive change and team training, establish parameters/indicators for RAPS operation, and facilitate communication among services across the country’s different realities. Narratives express this difficulty as follows:

E2: “What are we going to do? What does the patient need? Where do we refer them? Do we refer to them as CRAS? To the CREAS? To CAPS-AD? To mental health CAPS? Primary Health Care? I think a lot is missing, the network needs to know the patient is ours.”

E7: “Do you need to be hospitalized? Who do we call? Call the doctor? Coordinator Calls the doctor? We do not have private contact, as whoever is there will come to the day center? Do they return in the late afternoon? How will this work?”

E7: “Call Santa Casa? The mental health bed! Do we require hospitalization? Who do we call? Call the nurse? Call the coordinator? Call the doctor? Let us call and attempt to coordinate. If the patient is present, will they come to the CAPS? Will they come to the day’s center? Will they return in the late afternoon? How will this work? Now that we are starting to do this, negotiating with Santa Casa, they will come! However, sitting down and coordinating how this will work is on paper. Is it working? Is it flowing naturally? It’s not yet reality! The need arises; a case in Santa Casa! Is the patient from CAPS? What were they using? Call! Inquire! We check the medical record, discuss the case, we’re working based on what we’re discussing.”

E8: “Personally, before your study, I was unaware of this. Before you established the situation related to your study, I did not know about this service or its flow. We attended patients with this understanding of the operation, as if everyone were in their designated place, you know? We do not know about the child protection network. We know how care works and the flow for minors. Depending on the abuse situation, what to do in that situation is a small flowchart of the places providing care. So, but I missed being able to say, to have the authority to say, it works like this, like this, and like that. However, I miss not only regarding legislation but also knowing the city. What is the role of mental health CAPS? Of the Ad? Of the emergency department? Up to which patients can be taken to the emergency department? Can we treat certain conditions in mental health CAPS or in Ad itself? Therefore, it would be interesting to clarify this flow. I think that’s what you are looking for, right? It’s very interesting!”

We need to listen to these caregivers, understand their challenges and the hardships faced daily, and propose discussions to enhance professional development. Given these results, it is crucial to establish a space for these workers to voice their grievances and pain, where suffering can be addressed with the aim of creating favorable working conditions (FABRI; LOYOLA, 2014).

Urgent team meetings are needed, where the coordinator can elucidate the significance of each category within the field and collaborative work, striving for one common goal: treating patients with humanity and comprehensiveness and reintegrating them into society (ALMEIDA; FUREGATO, 2015).

Based on Machineski et al. (2017), it becomes apparent that the reform proposals advance as management mechanisms are created and implemented to expand the network of services, offering individuals psychological distress opportunities for social engagement. As elucidated, points of care are interconnected when facing demand. Interviewees presented challenges and perspectives for fortifying this network, where management and communication devices play central roles.

3.2 Challenges in mental health actions within primary care

The second thematic category focused on the challenges of mental health actions within Primary Care. According to the national policy of basic care, primary health care encompasses a set of individual and collective health actions, including health promotion, protection, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, harm reduction, and health maintenance. Its objective is to provide comprehensive care that impacts individuals’ health situations, autonomy, and the determinants and conditions of collective health (BRASIL, 2012). This category was divided into two subcategories that justify it: the absence of matrix support and difficulties with screening.

In relation to the absence of matrix support, there are two types of Psychosocial Care Centers: CAPS II for mental health and CAPS II for substance abuse. These devices are expected to act as coordinators and play a central role in health networks, fulfilling their roles in direct assistance, regulating the health service network, and promoting community life and users’ autonomy. They must work together with other social networks and related sectors as a form of support and effectiveness to include individuals (BRASIL, 2004, 2011).

Thus, statements demonstrate that the Psychosocial Care Centers in this municipality have already started this work with positive results. However, barriers hinder the continuation of these activities.

E1: “…but, that it’s stagnant, there are many, issues, activities that we’re really not continuing because of lack of human resources, due to financial resources as well, but we started this conversation, started this work, it was very productive.”

E4: “So, for example, if the patient is discharged? We had a single matrix support meeting, I remember it was the one when you and P3 did, after that we did not have more. So, we do not know what is right? The patient, they go to the health unit just to renew prescriptions, right!”

Matrix support is based on the assumption that management functions are carried out among individuals, albeit with varying degrees of knowledge and power, with the aim of ensuring specialized support for teams and professionals responsible for addressing health problems (CAMPOS, 2000).

E4: ” There is no reference, right? No reference, no counter-reference exists, but I think there’s much room for improvement in creating this reference, counter-reference, improving this communication.”

E6: “So, I think, the greater deficiency we find is in primary care…. And if we don’t start over and hope that primary care will really align with us, our work will be to receive the user, medicate the user, fulfill a therapeutic part that is also still lacking, and send the user back to the network so that they come back to us.”

E7: “…because we know that stabilized patients are discharged, but every now and then if primary care is not prepared to approach, to follow up, so we always have this feedback, they can easily come back. Being in crisis or taking appropriate medication because an external factor comes and a greater interference triggers a new crisis process. The fact of being discharged stabilized, but if we have contact to know how daily life is, these are patients who will return, and when they return, we see this fragility that is not being monitored.”

Given these challenges in integrating people with mental disorders into their communities, the Ministry of Health proposed a strategy of Matrix Support, or mental health matrix support, to facilitate the direction of flow in the network and promote coordination between mental health facilities and Primary Health Care. According to mental health coordination, in the document presented to the Regional Conference on Mental Health Services Reform, Matrix Support constitutes an organizational arrangement that enables specialized technical support in specific areas for teams responsible for developing basic health actions (BRASIL, 2008). The analysis revealed that matrix support is a practice that organizes and articulates services. Some points of care have already implemented this tool, with positive outcomes. Moreover, matrix support meetings can represent spaces for the reflection and construction of mental healthcare connected with life (BELOTTI; LAVRADOR, 2012).

In relation to difficulties with screening, the interviewees considered inadequate screening to be prevalent in patient-user relationships. Inadequate approach and technical and professional unpreparedness are identified as ineffective in assistance actions, not only at the primary level but also across all levels of healthcare.

E4: “I think of insecurity, you know, in dealing with this patient who has mental suffering. As I said, not every doctor wants to treat a patient, unless they are a psychiatrist, you know? I also do not know any nurse who has proposed any action for a specific group, for example, a mental health group. So, I think there’s insecurity in dealing with it.”

E4: “They receive follow-up at the CISAJE outpatient clinic, but effective actions that primary care takes with patients suffering from mental distress, I don’t know. It’s a group! To try to reintegrate, I do not see it. They go, they are welcomed, but for dealing with the problem they have at that moment, you understand?”

E5: “And restraint is also inadequate because I have attended patients who come from the bed, and they say, ‘I can’t get out of bed to defecate because I’m tied up there, and there’s no one to untie me when I need it.’ So, it’s inhumane.”

E7: “I was shocked! How can we have a quality RAPS when our mental health bed is inserted into a reality of medical clinics, with elderly patients, patients with other needs, and a patient restrained in bed?”

Therefore, the need for humanized care in mental health and interdisciplinary dialogue regarding the actions developed in this area is reinforced. Care contributes to the process of social and family reintegration of users with mental disorders and increasingly strengthens the ongoing Psychiatric Reform process (PESSOA JÚNIOR et al., 2016). The reform advances as management mechanisms are created and implemented to expand the network of services, which gives individuals psychological distress opportunities to live in society. (MACHINESKI et al., 2017).

3.3 User reception

The third and final thematic axes were classified as user reception based on the findings in the interviewees’ statements related to the shortage of human resources and excessive user demand. The insufficiency, absence, and turnover of professionals are highlighted as impactful for services, generating fragmented access, assistance, and resolution.

E1: “So, I mean, we do not have a clinician! We do not have coordination. We do not have any security. And so on! The shortages are very significant.”

This precariousness was also pointed out in qualitative research by Esperidião et al. (2015), who aimed to understand aspects related to the training and qualification of professionals working in Mental Health services in the interior of the state of Goias, Brazil. The results indicate an emerging need to invest in the training of professionals according to the Psychosocial Care model to work in Mental Health services as well as to ensure work connections that favor qualification and excellence in assistance.

E6: “…because we feel that this high turnover of employees, absence of doctors, right? … the CAPS went without coordination for nearly two years, there was a change in the entire professional team which brought about a significant loss for patients, for users, right?”

E6: “And today we have not been able to do it, why? Due to human resource issues…”

E7: “And the overall care network in Diamantina, right? Today, the Family Health Strategy units have nurses who are permanent, community health workers who have been rehired, and a whole new team. The CAPS also went through this change of substituting the new team, replacing other members, so all of this has an impact, yes!”

E8: “The mental health CAPS is currently without a specific psychiatric professional.”

A lack of working conditions directly affects the development of workers’ activities. Lack of knowledge in the field, turnover of professionals and absences, disorder in patient records, inadequate physical space for the service, lack of human and material resources to meet demand, and long working hours have been reported as factors that affect work quality (FILIZOLA; MILIONI; PAVARINI, 2008). In the exploratory and descriptive study by Almeida and Furegato (2016), the need for investment in specialized human resources training was highlighted. There is also a lack of knowledge exchange between professional categories working in these services, as most work in isolation.

It is crucial to recognize that despite the identified limitations, professionals can advocate for better working conditions and changes, both in health policies and in their actions towards greater collaboration and integration within the network. The findings suggest that strengths enhance mental health care, and vulnerabilities are barriers that need to be overcome in the hope of building an integrated and consolidated psychosocial care network in the investigated area. The RAPS provides care based on individuals’ capabilities and skills, increasing contractual commitments, and aiming to make the lives of people with severe and persistent mental disorders more dignified (JÚNIOR, et al., 2016).

The current scenario of mental disorders and their comorbidities is evident in a significant number of appointments across all three levels of healthcare. With this excessive user demand, there is an unprepared network in terms of both physical and human resources.

Chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCDs) have become the main health priority in Brazil, accounting for 72% of the deaths in 2007. Neuropsychiatric disorders have the largest contribution to CNCDs (SCHMIDT et al., 2011). These numbers continue to increase, necessitating greater attention to the care of individuals with mental disorders.

E1: “Here, after all, it is an emergency service, and we are dealing with emergencies. we are already deeply involved, because it is already a lot. Since it is a new service, today, like the previous CAPS, do you remember? The demand here is high today, and the movement is very high, right! Because the issue of alcohol and drugs is pulsating and becoming increasingly serious, the service tends to grow. And we see that, for example, P1 comes here for two half-hour shifts, you understand?”

E3: “And the tendency is only to grow.”

The findings also revealed the potential of a network that commits and collaborates using human resources as the main tool, which produces successful results.

E5: “I notice a lot of willingness from professionals in the network when discussing a case. I notice a lot of commitment from professionals; they want to know which patient, which medication, and why they did not return to the post after being discharged from CAPS. I perceive this in general, technical nursing staff and nurses.”

E6: “The most important aspect is the family approach. Because if you work with a family approach, the family itself automatically builds this care network, because they keep themselves informed about the references they have to use.”

E8: “Usually, we can do reception through conversation, spending whatever time is needed to calm a patient down, to try to show them their options.”

E9: “But, the person who’s attending doesn’t have that availability to say, ‘Come here, I’ll try to help you, let’s see what we can do to find out,’ because even if you don’t have…”

Through this analysis, it becomes evident that the identified strengths enhance mental health care, and the vulnerabilities serve as barriers to overcome, with the hope of establishing an integrated and consolidated psychosocial care network in the investigated area. It is ultimately considered that the RAPS offers care based on individuals’ capabilities and skills, increasing contractual commitments, and aiming to make the lives of people with severe and persistent mental disorders more dignified.

4. DISCUSSION

The establishment of healthcare networks has emerged as a complex endeavor, necessitating actions interlinked with other services and stakeholders for consolidation. Furthermore, it remains imperative for professionals within this network to comprehend their aims and functionalities to ensure effective care delivery. Hence, interdisciplinary engagement within a Psychosocial Support Network is poised to develop strategic articulation strategies, thereby fostering care enhancement and health production.

The significance of this study is underscored by its identification and description of aspects that challenge and facilitate the consolidation of the mental health network in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Despite these inherent limitations, an analysis of its functionality was performed. Although the network’s representation does not strictly conform to the proposed guidelines of the National Mental Health Policy, it unequivocally affirms its existence. This analysis warrants the celebration and acknowledgment of fragmented, yet resolution-oriented, multidisciplinary and intersectoral work. This research proposition underscores the necessity of a municipal mental health manager who engages in public policies, coordination, planning, and action monitoring to harmonize and integrate services.

Matricial support also surfaced as the principal avenue for integrating attention points, as exemplified by successful municipal experiences, albeit not contemporaneous. The challenges outlined include communication gaps among services, the absence of a governance system and matricial support, inadequate screening, insufficient human resources, and overwhelming user demand. These issues adversely affect weakened care points, resulting in a fragmented network of struggles in both primary healthcare actions and user reception.

Throughout the research exploration, I encountered constructive and destructive criticisms concerning our healthcare system, along with doubts, complacency, and disquiescence about the context prevailing within our nation. Venturing beyond complacency in pursuit of answers has led to numerous inquiries encompassing potential accomplishments, limitations, and perspectives. The path, particularly in the realm of mental health, is extensive and viable, although inherently challenging.

Fortuitously, 15 years of nursing experience has exposed me to individuals grappling with mental suffering or disorders compounded by the use of substances such as cracks, alcohol, and other drugs. Regrettably, a considerable portion of professionals, society, services, and even family members harbor stigma and bias in providing assistance to these users.

Engaging across all three tiers of health attention reinforces this assertion. The fragmented patient, akin to their network, traverses distinct care settings such as specialized services (CAPS), general medical clinics, and intensive care units. Regrettably, no coordination emerged from services or professionals across these disparate encounters, embodying the notorious phenomenon of revolving doors.

When cruel human actions are intrinsically linked to health issues, particularly mental disorders or those stemming from substance use, the juxtaposition of numerous obstacles to ensuring dignified care and respect for users, their families, health services, and professionals appears incongruous. These obstacles resonated vividly within the discourses, countering the principles of psychiatric reform. This underscores the necessity of amplifying the voices of these stakeholders, as reform transpires in the quotidian, often engendering a reform reformulation.

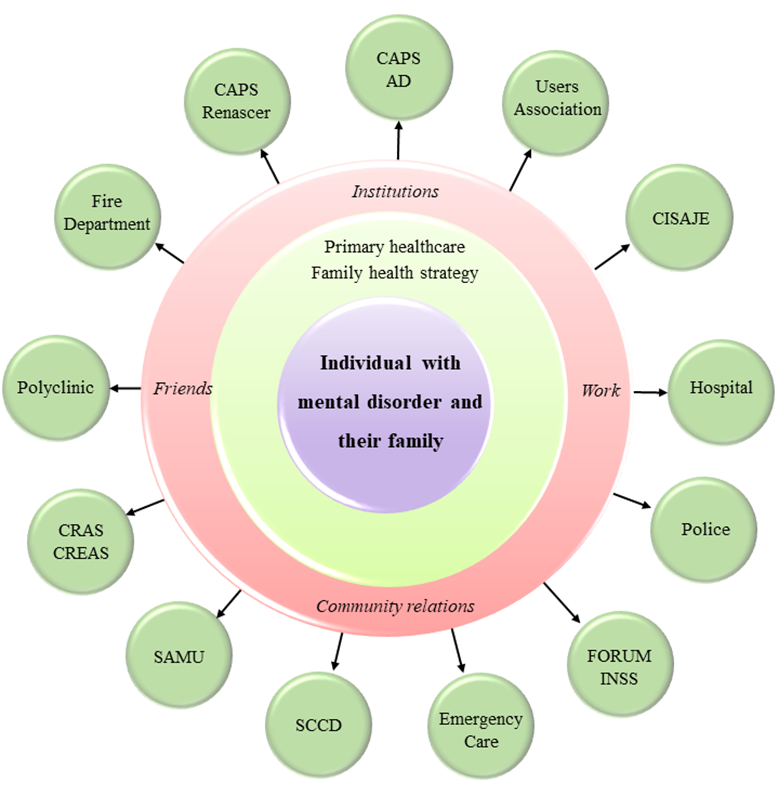

The partial blueprint of Diamantina’s mental health network is delineated in Figure 4, signifying the potential for further studies in this vital public policy realm, which remains curtailed by a dearth of investigations. Consequently, this conclusion does not mark its conclusion.

Figure 4: Components of the Diamantina psychosocial support network.

Figure 4 provides a comprehensive depiction of the components of Diamantina’s psychosocial support networks. Within this visual representation, the primary healthcare (PHC) system assumes a central and pivotal position, functioning as the orchestrator of the network and serving as the primary entry point to the Unified Health System (SUS). It is crucial to recognize that, while PHC plays a prominent role, the initial categorization underscores the network’s existence in a fragmented form. Despite concerted efforts to integrate various psychosocial care elements, the network’s complete harmonization and synergy remain aspirational goals.

Delving further into this discourse, the emphasis on PHC as the linchpin of the Psychosocial Support Network demands in-depth consideration. PHC’s centrality is not merely logistical, but also stems from its ability to act as a bridge between mental health services and the broader health system. The network’s aspiration to offer comprehensive and accessible care necessitates a robust PHC that can provide timely initial assessments, effective triage, and seamless referrals to specialized mental health services. While PHC’s pivotal role is undeniable, this study highlights the challenges in translating this vision into reality. Fragmentation, administrative changes, and technical glitches serve as reminders of the complexities inherent to network development and consolidation.

Additionally, the network’s composition indicates the intention to cater to a range of mental health needs through specialized points of care. However, the challenges elucidated in the study hint at a potential gap between the envisioned synergy and practical execution of these care points. The coordination required to ensure efficient patient flow, coherent treatment plans, and seamless transitions between care levels is a formidable task. The multifaceted nature of mental healthcare demands an integrated and synchronized approach, which is hindered by obstacles such as communication breakdowns and technical limitations.

To address these challenges, fostering a culture of inter-sectoral collaboration is essential. The network’s potential lies not only in the technicalities of care points, but also in the collective efforts of various stakeholders. Collaborative dialogue between PHC, specialized mental health units, emergency care services, and other relevant actors is imperative to bridge gaps, streamline processes, and ensure that patients experience a continuum of care rather than disjointed interventions. This participatory approach aligns with the core principles of user-centered care and reflects the broader aspiration of transforming mental health services into a holistic, person-centered system.

5. CONCLUSION

This study has unveiled a comprehensive understanding of the operational dynamics within the mental health network of Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil through meticulous qualitative exploration. Despite encountering challenges, including post-electoral administrative changes and technical obstacles, the study effectively garnered valuable insights from coordinators and collaborators directly engaged in mental healthcare delivery. The thematic oral history methodology facilitated a comprehensive description and evaluation of PCN functionality in Diamantina, MG. By delving into discussions with participants regarding their collaborative contributions within the network, this research has illuminated the impediments to its consolidation and put forth strategies to enhance the coherence and inclusiveness of access points. As we move forward, the findings underscore the significance of continuous commitment to network refinement, prioritizing user-centric care, and fostering intersectoral collaboration, all of which are pivotal for the progressive evolution of mental health care within the region.

The construction and operation of a PCN presents a multifaceted challenge, necessitating harmonized efforts among diverse services and stakeholders. Comprehension of goals and functionalities by professionals within this network is integral to ensuring efficient and integrated care for users. Interdisciplinary collaboration has emerged as a pivotal tool for developing coordination strategies that augment care and mental health promotion.

This study highlights a range of factors that simultaneously pose challenges and offers support for the consolidation of the mental health network in Diamantina/MG. The analysis revealed that despite its limitations, the PCN exists in practice, warranting acknowledgment for the resilience of the multidisciplinary and intersectoral approach, albeit fragmented efforts. Evidently, the presence of a municipal mental health manager actively engaged in public policies, coordination, planning, and monitoring holds pivotal importance in effectively articulating and integrating services.

Furthermore, the concept of matrix support has surfaced as a critical element for interlinking various points of attention within a network. Although successful experiences related to this approach have been identified in earlier phases, its present implementation appears to be compromised. Addressing the identified challenges, which encompass inadequate communication among services, the absence of a governance system, inadequate matrix support, insufficient screening, personnel shortages, and overwhelming user demand, is crucial for rectifying vulnerabilities within care points. This transformative effort aims to transition a fragmented network into a cohesive and efficient system. Amid the complexities and obstacles in the realm of mental health, it is paramount for psychiatric reform to progress not only theoretically but also in practice, amplifying the voices of stakeholders involved and driving incremental care transformation. As such, this research marks a significant stride in comprehending and fortifying PCN, instigating further inquiries to propel the advancement of this vital public policy.

REFERENCES

ALBERTI, V. Ouvir contar: textos em história oral. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2004.

ALMEIDA, A. S. de; FUREGATO, A. Regina Ferreira. Papéis e perfil dos profissionais que atuam nos serviços de saúde mental. Revista de Enfermagem e Atenção à Saúde. Uberaba, v. 4, n. 1, jan./jun.,2015.

ALVES, T. K. C. Identidade(s) Latino-Americana no Ensino de História: Um Estudo em Escolas de Ensino Médio Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. 206f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia 2011.

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1977.

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70 – Brasil, 2011.

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. Tradução de Luís Antero Neto e Augusto Pinheiro. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2006.

BELOTTI, M.; LAVRADOR, M. C. C. Apoio matricial: cartografando seus efeitos na rede de cuidados e no processo de desinstitucionalização da loucura. Revista Polis e Psique. Porto Alegre, v. 2, número temático, p. 128-146, 2012.

BRASIL. Centros de Atenção Psicossocial e Unidades de Acolhimento como lugares da atenção psicossocial nos territórios: orientações para elaboração de projetos de construção, reforma e ampliação de CAPS e de UA. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2015a.

BRASIL. Constituição Federal da República Federativa do Brasil: texto constitucional promulgado em 5 de outubro de 1988, com as alterações determinadas pelas Emendas Constitucionais de Revisão nos 1 a 6/94, pelas Emendas Constitucionais nos 1/92 a 91/2016 e pelo Decreto Legislativo no 186/2008. Brasília: Senado Federal, 2016.

BRASIL. Lei 10.216, de 6 de abril de 2001. Dispõe sobre a proteção e os direitos das pessoas portadoras de transtornos mentais e redireciona o modelo assistencial em saúde mental Diário Oficial da União. Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 9 abr. 2001. Disponível em: < http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10216.htm>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 3088, de 23 de dezembro de 2011. Institui a Rede de Atenção Psicossocial para pessoas com sofrimento ou transtorno mental e com necessidades decorrentes do uso de crack, álcool e outras drogas, no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da União. Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 26 dez. 2011. Disponível em: < https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2011/prt3088_23_12_2011_rep.html>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Saúde Mais Perto de Você. Portal do Departamento de Atenção Básica, Brasília, [201?]. Disponível em: <http://dab.saude.gov.br/portaldab/smp_ras.php?conteudo=rede_proprietaria>. Acesso em: 23 mar. 2017.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Saúde Mental em Dados. Informativo eletrônico. Brasília, ano 10, n. 12, out. 2015a. Disponível em: <http://portalarquivos.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2015/outubro/20/12-edicao-do-Saude-Mental-em-Dados.pdf>. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2016.

BRASIL. Política Nacional de Atenção Básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2012.

BRASIL. Portaria nº 336, de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Dispõe sobre os Centros de Atenção Psicossocial – CAPS, para atendimento público em saúde mental, isto é, pacientes com transtornos mentais severos e persistentes em sua área territorial, em regime de tratamento intensivo, semi-intensivo e não-intensivo. Diário Oficial da União. Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 20 fev. 2002. Disponível em: < https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2002/prt0336_19_02_2002.html>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

BRASIL. Portaria nº 4279, de 30 de dezembro de 2010. Estabelece diretrizes para a organização da Rede de Atenção à Saúde no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Diário Oficial da União. Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 31 dez. 2010. Disponível em: < http://conselho.saude.gov.br/ultimas_noticias/2011/img/07_jan_portaria4279_301210.pdf Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

BRASIL. Saúde mental: com identificação de problemas, Ministério quer melhorar a execução da Saúde Mental. Portal do Ministério da Saúde, 1 set. 2017a. Disponível em: < http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/cidadao/principal/agencia-saude/29448-com-identificacao-de-problemas-ministerio-quer-melhorar-a-execucao-da-saude-mental>. Acesso em: 20 ago. 2017.

BRASIL. Setembro Amarelo: Taxa de suicídio é maior em idosos com mais de 70 anos. Portal do Ministério da Saúde, 21 nov. 2017b. Disponível em: <http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/cidadao/principal/agencia-saude/29691-taxa-de-suicidio-e-maior-em-idosos-com-mais-de-70-anos>. Acesso em: 20 ago. 2017.

CAMPOS, G. W. S. Um método para análise e cogestão de coletivos. São Paulo: Hucitec 2000.

COSTA, Tiago Dutra da et al., CONTRIBUINDO PARA A EDUCAÇÃO PERMANENTE NA SAÚDE MENTAL.Biológicas & Saúde, [S.l.], v. 7, n. 23, mar. 2017. ISSN 2236-8868. Disponível em: <http://www.seer.perspectivasonline.com.br/index.php/biologicas_e_saude/article/view/647>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.25242/88687232017647.

DIMENSTEIN, M. et al., O atendimento da crise nos diversos componentes da rede de atenção psicossocial em Natal/RN. Revista Polis e Psique. Porto Alegre, v. 2, n. 3, p. 95-127, 2012. Disponível em: < http://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/PolisePsique/article/view/40323/25630>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

DUARTE, S. V.; FURTADO, M. S. V. Manual para Elaboração de Monografias e Projetos de Pesquisas. 3. ed. Montes Claros: UNIMONTES, 2002.

FABRI, J. M. G.; LOYOLA, C. M. D. Desafios e necessidades atuais da enfermagem psiquiátrica. Revista de enfermagem UFPE on line, v. 8, n. 3, p. 695-701, mar.2014. Disponível em: < https://periodicos.ufpe.br/revistas/revistaenfermagem/article/viewFile/9727/9818>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

FERREIRA, M. M.; AMADO, J. (Org.). Usos e abusos da história oral. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1998.

FILIZOLA, C. L. A.; MILONI, D. B.; PAVARINI, S. C. I. A vivência dos trabalhadores de um CAPS diante da nova organização do trabalho em equipe. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem, v. 10, n. 2, 2008. Disponível em: < https://www.revistas.ufg.br/fen/article/view/8061>. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

GIL, A. C. Como Elaborar Projetos de Pesquisa. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002.

JÚNIOR, JM, Santos RCA, Clementino FS, Oliveira KKD, Miranda FAN. Mental health policy in the context of psychiatric hospitals: Challenges and perspectives. Escola Anna Nery. 2016; 20 (1): [online] [acesso em 2018 Janeiro 20].

KINKER, F.; BARREIROS, C. Atenção psicossocial e cuidado. In: FRANCO, T. A; ZURBA, M. B (Org.). Álcool e outras drogas: da coerção à coesão. Florianópolis: Departamento de Saúde Pública/UFSC, 2014. Disponível em: < https://ares.unasus.gov.br/acervo/handle/ARES/1720?show=full >. Acesso em: 13 ago. 2023.

MACHINESKI, G. G.; SCHRAN, L. S.; CALDEIRA, S.; RIZZOTTO, M. L. F. A estrutura organizacional da rede de saúde mental brasileira: revisão integrativa. Varia Scientia-Ciências da Saúde. Cascavel, v. 3, n. 1, p. 55-62, jan./jun., 2017.

MEIHY, J. C. S. B. Manual de história oral. São Paulo: Loyola, 2002.

MENDES, E. V. As redes de atenção à saúde. 2. ed. Brasília: Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde, 2011.

MENDES, Eugênio Vilaça. As redes de atenção à saúde. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. Rio de Janeiro, v. 15, n. 5, p. 2297 – 2305, ago.2010.

MINAYO, M. C. S. O desafio do conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. 7. ed. São Paulo: Hucitec, 2000.

MINAYO, M. C. S. Pesquisa social: Teoria, método e criatividade. 2.ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1996.

NÓBREGA, M.; SILVA, G.; SENA, A. Funcionamento da Rede de Atenção Psicossocial-RAPS no município de São Paulo, Brasil: perspectivas para o cuidado em Saúde Mental. CIAIQ2016, Porto – Portugal, v. 2, p. 41 – 49, jul. 2016.

OLIVEIRA, S. L. de. Tratado de Metodologia Cientifica. 2. ed. São Paulo: Pioneira, 1999.

PESSOA JÚNIOR, J. M.; SANTOS, R. C. A.; CLEMENTINO, F. S.; OLIVEIRA, K. K. D.; MIRANDA, F. A. N. A política de saúde mental no contexto do hospital psiquiátrico: Desafios e perspectivas. Escola Anna Nery Revista de Enfermagem, v. 20, n. 1, p. 83 – 89, jan./mar., 2016.

RUIZ, J. A. Metodologia Científica: guia para eficiência nos estudos. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002.

SCHMIDT, M. I.; DUNCAN, B. B.; SILVA, G. A.; MENEZES, A. M.; MONTEIRO, C. A.; BARRETO, S. M.; CHOR, D.; MENEZES, P. R. Doenças crônicas não transmissíveis no Brasil: carga e desafios atuais. The Lancet, [online], maio 2011.

TURATO, E. R. Decidindo quais indivíduos estudar. In: Turato E. R. Tratado da metodologia da pesquisa clínico-qualitativa: construção teórico-epistemológica, discussão comparada e aplicação nas áreas de saúde e humanas. 3. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes; 2008.

[1] Nurse. Master’s degree in teaching and health from the Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys. Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. e-mail: marisaresendeparreira@gmail.com

[2] Nurse. PhD in Health Sciences from the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and the Mucuri Valleys. Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. e-mail: paulo.ferreira@ufvjm.edu.br

[3] Psychologist. Postdoctoral Researcher in the Health Sciences Program at the Federal University of Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys. Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Email: lilianymara@bol.com.br

[4] Professor at the Department of Nursing, Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. PhD in Health Sciences from the Faculty of Medicine, UFMG. e-mail: georgesobrinho@ufvjm.edu.br

[5] Medical Doctor. Psychiatrist. Professor at the Posgraduate Program in Health Sciences, Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Associate Professor – Mental Health, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys. PhD in Neuroscience, Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). Email: guilherme.nogueira@ufvjm.edu.br

[6] Professor at the Department of Nursing, Campus JK, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys, Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. PhD in Public Health from the Faculty of Medicine, UFMG