REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.12675000

Tainara Micaele Bezerra Peixoto¹

Jussara Peters Scheffer¹

Luciana de Macêdo Mello¹

Isabella Cristina Morales¹

Márcia Rezende Faes¹

Mariah Bianchi Reis Gusmão Petronilha¹

Rodiney Pinheiro Denevitz¹

André Lacerda de Abreu Oliveira¹*

ABSTRACT

Ureteral surgical interventions have had an increasing incidence in the veterinary routine and are indicated mainly for the treatment of trauma, congenital anomalies or relief of obstructions. Ureteral repair requires a longer time and the choice of the ideal suture directly contributes to the success of these procedures. The objective is to compare three different gauges of nylon for suturing the ureter using a microsurgical technique. Fifteen rabbits were divided into three groups, in which the right ureters were sutured in a partial perforating pattern, with three simple discontinuous stitches, using nylon 6-0 (Group N6), 8-0 (Group N8) and 10- 0 (group N10). Additionally, ultrasound evaluations were performed and, after euthanasia, on the thirtieth postoperative day, the kidneys and ureters were subjected to macroscopic and histopathological evaluations. The use of the 10-0 suture resulted in lower rates of ureteral inflammation, renal changes and postoperative complications when compared to the other two thicker gauges of the same suture material.

Keywords: Microsurgery, nylon suture, ureter, ureterotomy

INTRODUCTION

In ureteral sutures, the great challenge is represented by the choice of the ideal surgical suture material for its realization, being especially important the caliber used and its correlation with cases of morbidity and mortality in these procedures.

Ureteral surgeries in companion animals can be indicated for the treatment of trauma, congenital anomalies or obstructive uropathies due to intra or extramural injuries [29]. Ureterotomy is one of the most used traditional surgical techniques, especially for the removal of ureteral calculi in different species [4, 8, 9, 12, 15, 18, 19, 25, 27, 29].

After surgery, ureters have a delayed repair period and any intervention can cause disturbances during remodeling process [5] This fact, associated with the small size of these structures in animals, demands the use of a intraoperative microscopy to promote visual magnification and perform detailed procedures [14, 23, 24].

Suture materials play an important role, providing support for tissue healing during wound repair, and, in microsurgery, non-absorbable sutures have effective clinical responses [7]. The use of nylon monofilament induces minimal tissue reaction and maintains high levels of elasticity after implantation in the tissue, configuring a good choice when tissue edema and inflammation may occur [20, 28].

Despite the increasing use of microsurgery in several fields of veterinary medicine[14], descriptions of microsurgical ureterotomies [1, 4, 8, 9, 12, 15, 19, 25, 29] have been associated with several postoperative complications, such as uroabdomen, edema at the suture site and post-surgical stenosis, resulting in high mortality rates [15, 17]. It is worth noting that these studies use 5.0 to 8.0 suture gauge, do not standardize the magnification of the microscope and do not specify the needle used, therefore, it is likely that complications are associated with sutures that cause extensive tissue damage and compromise the lumen, predisposing to chronic inflammation, fibrosis and stenosis [5]. Furthermore, research comparing tissue reactions corresponding to the thickness of the threads used for suturing the ureter is scarce.

The objective is to compare the most appropriate nylon suture for performing ureterorrhaphy using the microsurgical technique in rabbits. The hypothesis is that the use of 10-0 suture and the non traumatic needle, provides less tissue reaction and adequate sealing of the micro sutures, reducing postoperative complications associated with ureterotomies, such as uroabdomen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was previously appreciated and approved by the Ethics and Animal Use Commission of the State University of North Fluminense – Darcy Ribeiro (protocol: 975023).

A total of 15 adult New Zealand rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) were used, weighing between 2.5 and 3.25 kg (average of 3.02 kg). Rabbits were used as an experimental model because they show ureteral anatomical similarities to cats, especially the ureteral diameter. The animals were acclimated individually in suspended wire cages, received water and standardized commercial food for rabbits (Nature Multivita, Socil Evialis Nutricao Animal Industria e Comercio LTDA, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais), ad libitum, and obtained routine veterinary care throughout the trial period.

All animals received pre-anesthetic medication consisting of ketamine hydrochloride (30 mg/kg, Cetamin, Syntec do Brasil LTDA, Santana de Parnaíba, São Paulo) and xylazine hydrochloride (3 mg/kg, Sedanew, Vetnil Industria e Comercio de Produtos Veteran LTDA, Louveira, São Paulo), administered intramuscularly. After 15 min, the animals were prepared for surgery according to standard aseptic technique and the antisepsis of the left pinnae were performed with alcohol 70 (Rialcool 70%, Rioquimica S.A., São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo) for later cannulation of the marginal vein with a 24 Gauge (24G) catheter (Mediplus India Ltda, Haryana, India). Anesthetic induction was performed with propofol (5mg/kg, Propovan, Cristalia Produtos Químicos Farmacêuticos LTDA, Itapira, São Paulo) intravenously and, soon after, the animals were intubated with a 2.5mm endotracheal tube and kept in 100% oxygen throughout the anesthesia. Maintenance of the anesthetic plan was achieved with the application of an intermittent bolus of propofol.

All surgical procedures were performed by the same surgeon and, following the aseptic technique principles. The patients were positioned in dorsal recumbency and surgical access was performed through median retro umbilical laparotomy.

The right ureter was identified and isolated from the retroperitoneum with the aid of blunt dissection. A vascular clamp was placed over the middle third of the ureter in order to stabilize and isolate the incision site, in addition to temporarily occlude urinary flow. From that moment on, the surgical microscope was used (20x magnification) and the longitudinal incision in the 2 mm ureter was performed using a number 11 surgical blade (Solidor, Labor Import Com. Imp. Exp. Ltda., Osasco, São Paulo).

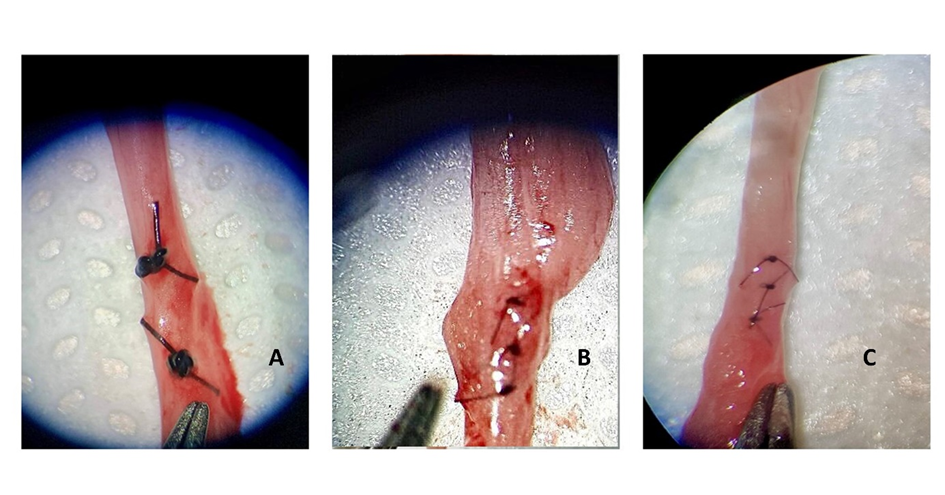

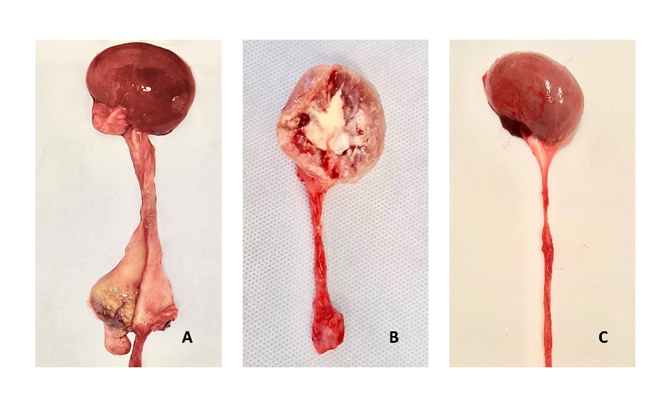

For ureterorrhaphy, the animals were randomly divided into three groups of five, in which the 6-0, 8-0 and 10-0 gauges of the nylon suture (Atrmat do Brasil Ltda, Braganca Paulista, São Paulo) the ureteral suture in the groups named N6, N8 and N10, respectively. The contralateral ureters served as the control for the animal itself. Three partial perforating sutures were performed (Figure 1) in a simple discontinuous pattern with an atraumatic needle. Immediately after the vascular clamp was removed, and the presence of possible urinary leakage was verified, the ureter was anatomically repositioned. The abdominal cavity was closed using 2-0 nylon suture (Brasuture Industria Comercio Importacao e Exportacao Ltda, São Sebastião da Grama, São Paulo) with a Sultan suture pattern in the muscle layer; polyglactin 910 of 2-0 gauge (Atrmat do Brasil Ltda, Braganca Paulista, São Paulo) with Cushing suture pattern to approach the subcutaneous tissue and nylon 3-0 (Brasuture Industria Comercio Importacao e Exportacao Ltda, São Sebastião da Grama, São Paulo) in simple continuous pattern for skin suture.

Figure 1: Illustrative image of ureterorrhaphy in partial perforating pattern. (A) 6-0 nylon suture; (B) 8-0 nylon suture; (C) 10-0 nylon suture.

The therapies were instituted in the immediate postoperative period and lasted for 5 days, in which ceftriaxone was administered (30 mg/kg, Ceftriaxona Dissódica Hemieptaidratada, Blau Farmacêutica S. A., Cotia, São Paulo) twice a day, intramusculary; metamizole sodium (25 mg/kg, Analgex V, Agener Uninao Distribuidora de Medicamentos LTDA, Taboao da Serra, São Paulo) once a day, subcutaneously and tramadol hydrochloride (Tramadon, Cristalia Produtos Químicos Farmacêuticos LTDA, Itapira, São Paulo), at a dose of 5 mg.kg-1, twice a day, intramusculary.

Ultrasound evaluations occurred in two parts, on the 5th and 30th postoperative days, respectively. The examinations were evaluated the length and width of the kidney, the presence of nephrolites, dilation of the pelvis, the diameter of the ureter and the presence of free liquid in the abdominal cavity. The animals were not sedated for the examination, then, positioned in dorsal recumbency on a padded trough and an acoustic gel was applied to improve the contact between the gel and the transducer. The evaluations were performed using Mindray® model Z6 equipment, with linear and convex multifrequency transducers, ranging between 3 and 10 MHz’s.

The animals were euthanized 30 days after the surgical procedure. Rabbits were pre-medicated with ketamine hydrochloride (30 mg/kg) and Midazolam (3 mg/kg, Dormire, Cristalia Produtos Químicos Farmacêuticos LTDA, Itapira, São Paulo), intramusculary. After 15 min, the animals had the marginal vein of the left auricular pavilion cannulated with a 24G catheter and an overdose of propofol was administered. After achieving the right anesthetic plan, 5 mL of IV potassium chloride was administered (Samtec Biotecnologia, Ribeirão Preto São Paulo).

MACROSCOPIC EVALUATION

During necropsy, the entire abdominal cavity was examined in order to compile macroscopic changes related to the surgical procedure. The kidneys and ureters were analyzed for the form and presence of hydronephrosis or dilation, respectively. The abdominal cavity was assessed for the presence of free liquid.

MICROSCOPY EVALUATION

Tissue fragments were obtained from the kidneys and the ureteral portion containing the suture and proceed to fixation in 10% neutral formalin buffered for at least 48 h. Then, the samples were cleaved and subjected to histological processing in the TP 1020 Leica automatic processor, obtaining histological sections of 5 micrometers thick. The sections were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining (H / E) and analyzed by an experienced pathologist through light microscopy.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Using the software Graphpad Prism version 5.0, the analysis of the quantitative variables was done through one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with a subsequent Newmann-Keuls, Tukey and T Student average test, depending on each case, if p <0.05 (99.95% reliability). For qualitative variables, the Mann-Whitney, Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were used.

Histological results were analyzed using a median of scores (descriptive statistics), by grading the severity of the lesions found, according to the independent observer’s assessment. Scores were assigned according to the estimated percentage of lesions appearing in the observed field.

Table 1: Scores attributed according to the estimated percentage of the appearance of inflammatory cells in the ureters observed Percentage of Lesions Classification Score Until 25% Light 1 From 25 to 50% Moderate 2 From 50 to 75% Intense 3 Above de 75% Severe 4 Table 2: Scores attributed according to the estimated severity of fibrosis and degeneration in the kidneys evaluated. Classification Score Absent 0 Discrete focal 1 Discrete multifocal 2 Moderate multifocal 3 Accentuated diffuse 4

RESULTS

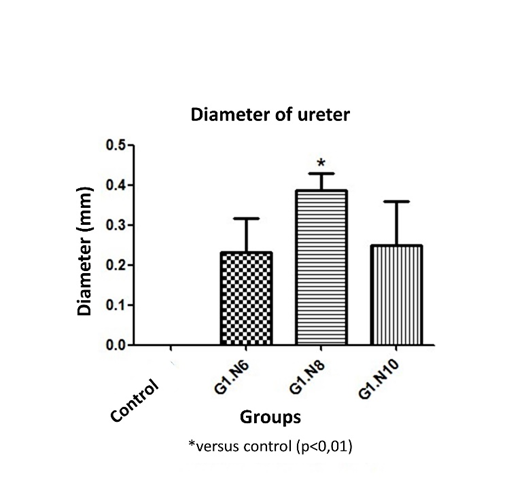

In the first ultrasound assessment, the 3 groups showed a difference in renal length (p <0.048) in relation to the control, but not between them, and, although all of them presented larger measurements in width, this was not significant. It was possible to observe that the measurements increased according to the thickness of the wire used. Only the N8 showed a difference in relation to the ureteral diameter (p <0.01) (figure 2). The renal pelvis dilated in 4/5 N6 animals; 5/5 animals from the N8 and 3/5 from the N10. None of the 15 animals presented lithiasis in the first ultrasound assessment.

Figure 2: Comparative graph of the values of ureteral diameter obtained on ultrasound for the fifth day after surgery. The 8-0 suture was the only one to obtain a difference with the control group.

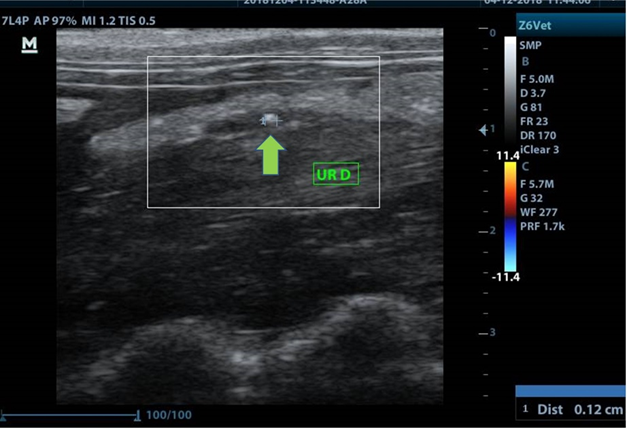

In the 25-day interval between the two ultrasound assessments, 4 N6 animals died due to severe peritonitis. Thus, when comparing renal morphometric measurements, it is possible to observe a difference between all groups, including the control, with the N6 (p <0.0001). The measurements of renal length and width between N8 and N10 showed no difference between them. The ureteral diameter of these two groups was similar at 30 days, in which N8 decreased considerably compared to the first exam. The only N6 ureter evaluated at 30 days did not dilate. No pelvic dilation was found in groups N8 and N10, however, there was formation of lithiasis in 2 animals operated with 8-0 caliber (figure 3).

Figure 3: Ultrasound image showing the formation of ureteral calculus at the suture site (green arrow).

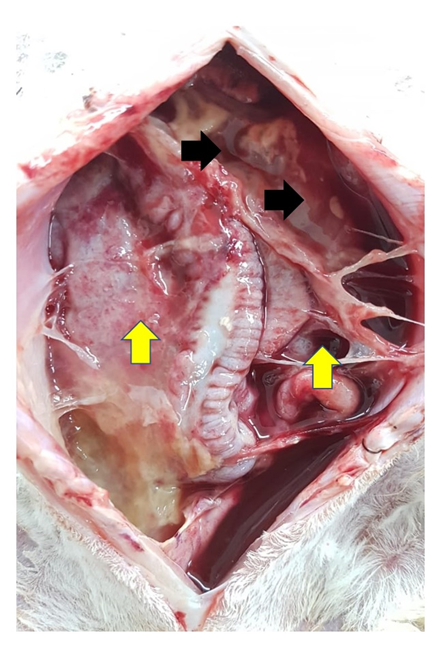

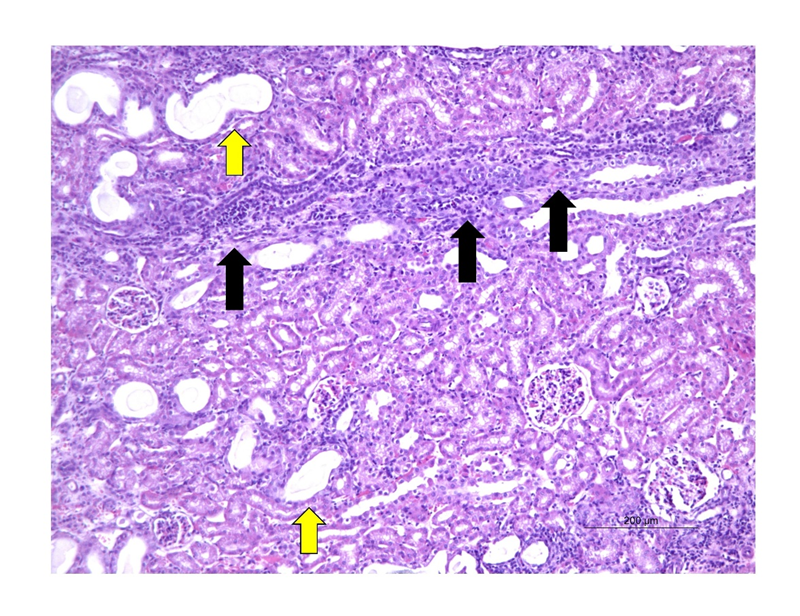

The 4 animals that died on the N6 had a large amount of free liquid with blood in the abdominal cavity and diffuse peritonitis (figure 4). The only surviving animal developed hydronephrosis. Group N8 obtained the largest number of animals with altered kidney contour (2/5), in which, when cut, these kidneys showed changes in the corticomedullary junction pattern and the presence of caseous content. In N10, a single kidney developed hydronephrosis with the presence of a caseous content at the cut.

Figure 4:Presence of free fluid (black arrows) associated with severe peritonitis (yellow arrows) at necropsy of the animal operated with 6-0 suture.

Only the N8 presented alteration of the ureteral form macroscopically, where one of them dilated considerably and the other developed stenosis. In N6, a ureter presented blackened areas in the kidneys and at the suture site (figure 5).

Figure 5: Illustrative image comparing macroscopic changes in the sutured region of the ureter (asterisk); (A) Ureter operated with 6-0 nylon with extensive fibrosis at the suture site; (B) ureter operated with 8-0 nylon, with the presence of fibrosis at the sutur suture site, presence of caseous content in the kidney and alteration of the cortico-medullary pattern; (C) ureter operated with 10-0 nylon with no changes at the suture site.

On microscopy, a total of 11/15 of the kidneys evaluated had focal inflammations, where 3 of these belonged to N6; 5 to N8 and 4 to N10 (figure 6). The infiltrates were characterized mainly by heterophiles, lymphocytes and rare plasmocytes associated with tubules enlarged in size, with large and multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles, with evident and pycnotic nuclei, characterizing active chronic interstitial nephritis. Only 2 kidneys from subgroup N8 and 1 from subgroup N10 showed mild focal fibrosis, showing no difference with the control group. 2/5 of the kidneys at N6 showed areas of necrosis.

Figure 6: Photomicrograph showing multifocal active chronic interstitial nephritis (black arrows), associated with areas of multifocal degeneration, with tubules enlarged in size (green arrows) in a kidney belonging to group N6 (20x magnification, H&E staining).

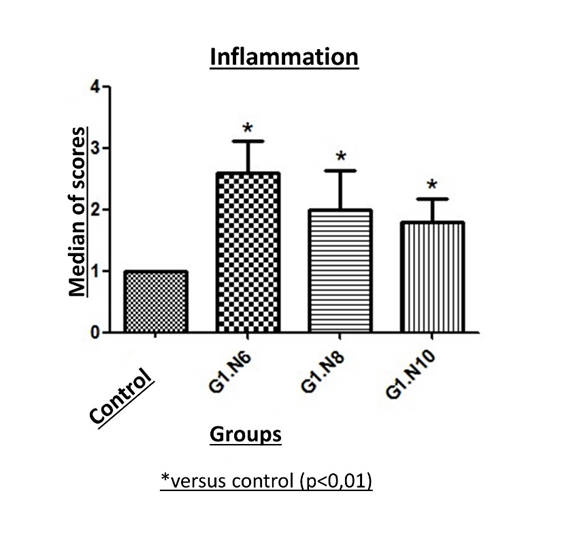

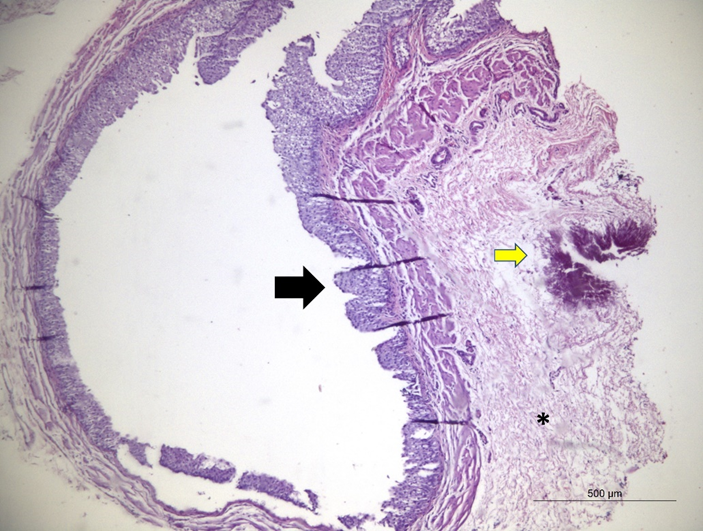

As for ureteral inflammation, the 3 groups showed a difference in relation to the control group, with the highest scores associated with thicker suture materials (figure 7). In N6, proliferation of giant cells encompassing the suture was observed, associated with a high proliferation of periureteral connective tissue (figure 8).

Figure 7: Comparison of the ureteral inflammation scores at the suture site attributed to the different suture gauges. The 3 groups obtained a difference with the control group and the scores increased according to the increase in the suture gauge.

Figure 8: Photomicrograph of the ureter operated with 8-0 suture, showing dilation with preserved mucous membranes (black arrow). In adventitious connective tissue proliferation, in between the inflammatory infiltrate represented by heterophiles, macrophages and lymphocytes (asterisk), associated with the mineralization focal area (yellow arrow). (4x magnification, H&E coloring).

DISCUSSION

Commonly 6-0 to 8-0 gauge are used for ureteral suture in felines [1, 4, 8, 9, 12, 15, 18, 19, 25, 27, 29],whose outside diameter is equivalent to that of New Zealand rabbits, corresponding to 1mm [21]. The thickness of the 6-0, 8-0 and 10-0 sutures represents, respectively, 0,07 mm, 0,04 mm and 0,02 mm [6, 31], and although the three gauges are considered thin for general surgical procedures, it is noted that, for millimeter structures such as the ureter, this difference is an important characteristic regarding to the non-compromise of the lumen. Using thicker sutures, coupled with traumatic needles and with the inappropriate aid of magnification, makes ureterorrhaphy a challenging procedure, corroborating the high rates of complications described so far [1, 4, 8, 15].

Due to the widespread use of rabbits in experimental research, some studies describe and compare the measurements and sonographic characteristics of healthy animals [3, 11, 26]. They all point to a positive correlation between kidney measurements and animal weight, which can also be observed in this study, because, despite the measures of renal length and width of the control group, consisting of the non-operated contralateral kidney and ureter, being smaller than those described for white New Zealand rabbits, the animals used here had a lower average weight, justifying the difference found [26]. In addition, another study, obtained similar renal measurements in 21 mixed breed animals, having an average weight equivalent to that reported in this study [3].

Changes in kidney size have been correlated with kidney disease and some specific pathological processes, such as hydronephrosis, are involved in increasing length and width [2]. In the first ultrasound assessment, all groups obtained differences with the control group, but not between them when comparing renal length. The width obtained more discreet increases, showing no difference with the control. Considering that acute changes result in larger kidneys, it is possible to correlate the increase in these measures with inflammation and ureteral edema resulting from the surgical procedure, causing luminal narrowing and urine accumulation in the kidney in different proportions [8]. These results are reinforced by comparing the data obtained in the second ultrasound assessment, where the difference significant length and width were no longer with the control group but with the N6, due to the loss of experimental plots.

The remodeling and the repairing of the operated tissue is directly related to the diameter of the suture material, so, with the exception of the renal width at 30 days, it is possible to observe that, in the two ultrasound evaluations, the renal measurements developed largest changes according to the greater caliber of the suture used. In relation to the renal pelvis, when there is no dilation, this structure is not normally seen on ultrasound and subtle dilations may also go unnoticed [3, 10, 30]. The dilation indices obtained in this study corresponded to the ureteral dilation seen in the ultrasound exams, in which the N8 had the largest ureteral diameters in the first exam and all animals in this group presented the pelvis dilated. The other two groups showed decreasing changes for pelvic dilation and ureteral diameter, according to the thickness of the suture material used (4 animals in N6 and 3 in N10). At 30 days, these two parameters decreased in all groups, particularly in N6 due to the loss of experimental plots, reaffirming that the increase in measurements occurs mainly due to acute changes [8, 10].

The ureters follow the pattern of the renal pelvis and are only seen on ultrasound when they are dilated and the group operated with 8.0 caliber suture was the only one that developed a significant increase in diameter in the first ultrasound assessment [4, 10, 12, 16]. The animals in this group also had high scores for ureteral inflammation, presence of stenosis and dilation at the suture site, in addition to macroscopic renal changes in greater numbers. Although widely used to perform ureterorrhaphy, 8-0 sutures are associated with high rates of postoperative complications, making them unsuitable for this procedure in ureters of rabbits, or other species with similar ureteral diameter [1, 4, 8, 9, 12, 15, 18, 19, 25, 27, 29]. Although the 10-0 obtained slight increases in ureteral diameter in the first and second exams, these were not significant and reduced considerably between the two evaluations. These results suggest that the use of a thinner material in the ureteral suture is more appropriate [8].

It is believed that the non-dilation of the ureters of group N6 is associated with urinary leakage into the abdominal cavity and consequent uroabdomen, since the majority of animals operated with this gauge of suture died between the two evaluations and a substantial amount of free liquid on necropsy exams, associated with severe peritonitis was found. The uroabdomen is the most frequently described postoperative complication in association with ureterotomies [4, 9, 12, 13, 15, 17, 19, 25, 29]. However, confirmatory tests comparing serum creatinine and that present in free abdominal fluid were not performed.

Although non-absorbable suture materials are not recommended for use in urinary tract surgeries due to the greater probability of acting as a starting point for the formation of stones [28], a recente study evaluated the behavior of 3 synthetic absorbable suture materials in rabbit urinary vesicles in 2 phases and the formation of lithiasis was observed between the 3rd and 6th week in two of the groups evaluated [30]. Thus, the formation of lithiasis seems to be more associated with the contact of the suture thread with the urine, and the tissue-thread behavior is directly related to the diameter used or to the presence of inflammation, infection, urinary pH and longevity of the material [22, 28]. In the present study, the group operated with 8-0 caliber was the only one to present formation of lithiasis in the 4th week after surgery, a time similar to the study mentioned above, and it is likely that, because it has a thicker caliber, this suture has come into contact with the urothelium. The non-formation of stones in the N6 group may be associated with the early death of the animals. Microscopically, in the N6 group, areas of necrosis were observed, validating the blackened areas found in macroscopy. Even though this group presented the same amount of alterations in the 10-0 caliber renal form, this can be explained by the early death of the animals due to extravasation and peritonitis. This fact is also associated with the non-occurrence of fibrosis in this group, since this response results from prolonged inflammatory processes [4, 8].

Any ureteral surgical intervention can cause a disturbance in the healing remodeling phase, resulting in fibrosis, obstruction in various degrees and consequent hydronephrosis [5]. Therefore, despite presenting hydronephrosis and renal and ureteral inflammatory changes, according to the results presented, it is noted that these numbers are lower with the 10.0 suture and that these changes occur mainly acutely, in the immediate postoperative period, reducing with the progression of ureteral healing. The limitations of this study include not performing tests for serum creatinine and abdominal fluid to confirm urinary leakage in one of the groups, as previously discussed, and not performing a histopathological evaluation at 5 days postoperatively, to ascertain the changes caused acutely by sutures. In particular, this was not done in order to reduce the number of animals used, since it would be necessary to have a larger number of samples in each group for the histopathological evaluation in two stages.

In conclusion, the 10.0-gauge suture resulted in lower scores of ureteral inflammations at the suture site, low postoperative complications associated with the procedure, in addition to minor acute and chronic changes in the kidney, making the gauge suitable for performing ureterorrhaphy in rabbits. Additional experimental and clinical studies need to be carried out in the long term to elucidate changes in the urinary tract and evaluate the survival of animals submitted to the procedure.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Tainara Micaele Bezerra Peixoto was the recipient of fellowship from CAPES, Brasil (2018/20).

REFERENCES

1. Adin, C. A. and Scansen, B. A. 2011. Complications of upper urinary tract surgery in companion animals. Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice. 41: 869–888.

2. Agopian, R. G., Guimarães, K. P., Fernandes, R. A., Vinícius Silva, M. M., Righetti, M. M., Rosana Duarte Prisco, C., Bombonato, P. P. and Aparecido Liberti, E. 2016. Estudo morfométrico de rins em felinos domésticos (Felis catus). Pesquisa Veterinaria Brasileira. 36: 329–338.

3. Banzato, T., Bellini, L., Contiero, B., Selleri, P. and Zotti, A. 2015. Abdominal ultrasound features and reference values in 21 healthy rabbits. Veterinary Record. 176: 101.

4. Berent, A. C. 2011. Ureteral obstructions in dogs and cats: A review of traditional and new interventional diagnostic and therapeutic options. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 21: 86–103.

5. Bhatnagar, B. N. S. and Chansouria, J. P. N. 2004. Healing process in the ureter: an experimental study in dogs. Journal Wound Care. 13: 97–100.

6. Brazilian Association of Technical Standards 2003. NBR 13904. Surgical suture threads. 1:.

7. Chen, L. E., Seaber, A. v and Urbaniak, J. R. 1993. Comparison of 10-0 Polypropilene and 10-0 Nylon sutures in rat arterial anastomosis. Microsurgery. 14: 328–333.

8. Clarke, D. L. 2018. Feline ureteral obstructions Part 2: surgical management. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 59: 385–397.

9. Culp, W. T. N., Palm, C. A., Hsueh, C., Mayhew, P. D., Hunt, G. B., Johnson, E. G. and Dobratz, K. J. 2016. Outcome in cats with benign ureteral obstructions treated by means of ureteral stenting versus ureterotomy. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 249: 1292–1300.

10. Debruyn, K., Haers, H., Combes, A., Paepe, D., Peremans, K., Vanderperren, K. and Saunders, J. H. 2012. Ultrasonography of the feline kidney: Technique, anatomy and changes associated with disease. Journal Feline Medical Surgery. 14: 794–803.

11. Dimitrov, R. S. 2012. Ultrasound features of kidneys in the rabbit (oryctolagus cuniculus). Veterinary World. 5: 274–278.

12. Hardie, E. M. and Kyles, A. E. 2004. Management of ureteral obstruction. Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice. 34: 989–1010.

13. Horowitz, C., Berent, A., Weisse, C., Langston, C. and Bagley, D. 2013. Predictors of outcome for cats with ureteral obstructions after interventional management using ureteral stents or a subcutaneous ureteral bypass device. Journal Feline Medical Surgery. 15: 1052–1062.

14. Kobayashi, E. and Haga, J. 2016. Translational microsurgery. A new platform for transplantation research. Acta Cirurgica Brasileira. 31: 212–216.

15. Kyles, A. E., Hardie, E. M., Wooden, B. G., Adin, C. A., Stone, E. A., Gregory, C. R., Mathews, K. G., Cowgill, L. D., Vaden, S., Nyland, T. G. and Ling, G. v 2005. Management and outcome of cats with ureteral calculi: 153 cases (1984–2002). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 226: 937–944.

16. Lamb, C. R., Cortellini, S. and Halfacree, Z. 2018. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of cats with ureteral obstruction. Journal Feline Medical Surgery. 20: 15–22.

17. Langston, C., Palma, D. and Mccue, J. 2010. Methods of Urolith Removal. Compendium: Continuind Education for Veterinarians.

18. Lanz, O. I. and Waldron, D. R. 2000. Renal and ureteral surgery in dogs. Clinical Technology Small Animal Practices. 15: 1–10.

19. Livet, V., Pillard, P., Goy-Thollot, I., Maleca, D., Cabon, Q., Remy, D., Fau, D., Viguier, É., Pouzot, C., Carozzo, C. and Cachon, T. 2017. Placement of subcutaneous ureteral bypasses without fluoroscopic guidance in cats with ureteral obstruction: 19 cases (2014–2016). Journal Feline Medical Surgery. 19: 1030–1039.

20. McFadden, M. S. 2011. Suture Materials and Suture Selection for Use in Exotic Pet Surgical Procedures. Journal Exotic Pet Medical. 20: 173–181.

21. Millward, S. F., Thijssen, A. M., Robert Marriner, J., Moors, D. E. and Mai, K. T. 1991. Effect of a Metallic Balloon-expanded Stent on Normal Rabbit Ureter. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2: 557–560.

22. Morris, M. C., Baquero, A., Redovan, E., Mahoney, E. and Bannett, A. D. 1986. Urolithiasis on absorbable and non-absorbable suture materials in the rabbit bladder. Journal of Urology. 135: 602–603.

23. Phillips, H., Ellison, G. W., Mathews, K. G., Aronson, L. R., Schmiedt, C. W., Robello, G., Selmic, L. E. and Gregory, C. R. 2018. Validation of a model of feline ureteral obstruction as a tool for teaching microsurgery to veterinary surgeons. Veterinary Surgery. 47: 357–366.

24. Pratt, G. F., Rozen, W. M., Chubb, D., Whitaker, I. S., Grinsell, D., Ashton, M. W. and Acosta, R. 2010. Modern adjuncts and technologies in microsurgery: An historical and evidence-based review. Microsurgery. 30: 657–666.

25. Roberts, S. F., Aronson, L. R. and Brown, D. C. 2011. Postoperative Mortality in Cats After Ureterolithotomy. Veterinary Surgery. 40: 438–443.

26. Silva, da K. G., Nascimento, L. v., Tasqueti, U. I., de Andrade, C., Froes, T. R. and Sotomaior, C. S. 2017. Características ultrassonográficas de fígado, vesícula biliar, rins, vesícula urinária e jejuno em coelhos jovens e adultos. Pesquisa Veterinaria Brasileira. 37: 415–423.

27. Snyder, D. M., Steffey, M. A., Mehler, S. J., Drobatz, K. J. and Aronson, L. R. 2004. Diagnosis and surgical management of ureteral calculi in dogs: 16 cases (1990–2003). N Z Veterinary Journal. 53: 19–25.

28. Tan, R., Bell, R., Dowling, B. A. and Dart, A. J. 2003. Suture materials: composition and applications in vetern-ary wound repair. Clinical Aust Veterinary J. 81:.

29. Wormser, C., Clarke, D. L. and Aronson, L. R. 2016. Outcomes of ureteral surgery and ureteral stenting in cats: 117 cases (2006–2014). Journal oh the American Veterinary Medical Association. 248: 518–525.

30. Yalcin, S., Kibar, Y., Tokas, T., Gezginci, E., Günal, A., Ölcücü, M. T., Özgök, I. Y. and Gözen, A. S. 2018. In Vivo Comparison of “V-Loc 90 Wound Closure Device” With “Vicryl” and “Monocryl” in Regard to Tissue Reaction in a Rabbit Bladder Model. Urology. 116: 231.e1-231.e5.

31. U.S.Pharmacopeia. http://ftp.uspbpep.com/v29240/usp29nf24s0_m80200.html.

¹Animal Experimentation Unit, State University of Northern Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro. Avenue Alberto Lamego, 2000, 28013-602, Campos dos Goytacazes,Rio de Janeiro, Brasil.

*Correspondence to: André Lacerda de Abreu Oliveira; Avenue Alberto Lamego, 2000, 28013-602, Campos dos Goytacazes,Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. (Darcy Ribeiro North Fluminense State University); lacerdavet@uol.com.br