REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/th10249031234

Quadro, Lsg¹ ²*

Behenck ,As²

Zachia, As²

Sarvacinski, F³

Kuhl, Cp³

Berger, M²

Passos, Ep³

Terraciano, Pb²

ABSTRACT:

Introduction: The inability to conceive children is a serious public health problem and although it is not a life-threatening, it can be linked to mental, social problems, and for quality of life. Objective: To assess whether infertility impairs the quality of life of women and their partners. Method: The study was guided by a descriptive cross-sectional observational design. Data from 59 couples were analyzed, between 25 and 40 years of age, enrolled in the assisted reproduction program of the Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre. The instruments used were: World Health Organization Quality of Life, BREF version (WHOQOL-BREF), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Spiritual Well-Being Scale and socio-demographic questionnaire, by signing the Free and Informed Consent Term Enlightened. Results: The predominant religion was Catholic with 23 women (39.0%) and 32 men (54.2%). Women got an average of 04 points and men 03 points in the weighted average of 6 on the BAI scale. Women who do not have a religion performed better in the physical domain of the BREF (64.3%). Men who live with other people and/or family members besides their wives have better QoL scores in the physical and psychological domains. There was an incidence of high QoL scores in the social domain in men who do not earn well. Anxiety in women, even at levels considered low, seems to interfere with existential well-being and QoL. Conclusion: We showed the multiple factors that consist the problem, whose frustration was present in both men and women. The nursing work in this situation presented as essential to know the demands of this population.

Keywords: Infertility, infertile couple, assisted reproduction, quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Historically, both infertility (difficulty in conceiving) and sterility (total impossibility of this happening) are reasons for unpleasantness between men and women (ILSKA et al., 2020). The biological child is socially surrounded by many expectations from the couple. This aspect is so present in certain cultures to the point where a woman doesn’t feel complete until she can be a mother (SANTOS, 2019; MCCARTHY, 2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines infertility as a disease of the reproductive system, translated by the inability to obtain a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular sexual intercourse and without using contraceptives (LEÃO & LINDÔSO, 2020). Two types of infertility are known, the primary and the secondary. The first occurs when the couple is unable to conceive and in the second case, the couple is unable to carry the pregnancy to the end, after having conceived. Infertility results from the failure of the reproductive process, as a result most often from an organic affection of the female, male or both reproductive systems (SANTOS et al., 2020).

It is presumed worldwide that between 40 and 80 million couples are infertile. (INHORN & PATRIZIO, 2015). Statistics point to a percentage of 0.6% and 32.6% of the world population suffering from the problem, varying according to the researched place (PASSOS, 2017). It is estimated that 30% of infertility cases are female, 30% male, 20-30% due to mixed causes and around 10 – 20% of unknown or idiopathic origin (AGARWAL et al., 2015). Female causes are related to ovulatory processes, gynecological pathologies, such as endometriosis and tubal disease. The most common male factors are: low sperm production, ductal obstruction, inability to deposit sperm in the vagina and immunological factors (ZAER et al., 2020; SIRISTATIDIS et al., 2020).

For the reasons presented here, we see infertility as part of a psycho social issue, which we want to investigate. To do so, we directed certain instruments to a population of infertile homes to know both their quality of life and the WHOQOL-BREF (FLECK et al., 2000) – World Health Organization Quality of Life -, if there is the presence of significant levels of anxiety when using the Anxiety Inventory of Beck – BAI (BAPTISTA, CARNEIRO, 2011), how is its relationship with the most transcendental meaning of life with the Scale of Spiritual Well-Being – EBE (MARQUES, SARRIERA, DELL’AGLIO, 2009) and, finally, to know the conditions of this population with the Socio-Demographic Questionnaire.

Methodology:

The frequencies of the data were described using the average and standard deviation (+-sd). The comparison between the WHOQOL-BREF scores of the patients and their partners was performed using the Student’s t-test for paired samples and the inter class correlation coefficient.

The study variables were grouped into timely related blocks. At first 03 (three) blocks were considered: block 1 (age, time living together and level of education), block 2 (diagnosis time, infertility cause and number of performed treatments) and block 3 (scores obtained with the WHOQOL-BREF, EBE and BAI applications). Hierarchical multiple linear regression was performed, which is a form of modeling where all variables from a specified block are inserted into the model at the same time, respecting the permanence of the significant variable for the entry of the next block with all the study variables. Variables that presented (p) less than 0.10 in their block were inserted in the subsequent block. Thus, the associated variables were evaluated independently from the others. Considering a significance level of 5%, power of 80% and a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.27 between the variables under study with quality of life, a minimum total of 106 couples was obtained.

Discussion of results:

When couples resort to assisted reproduction techniques, they usually deal with the situation for some time. The difficulty in conceiving, for many, has overwhelming dimensions. Studies associate marital infertility as a cause for numerous emotional disorders such as anxiety, anger and depression (RAMEZANZADEH et al., 2004; BRENNAN, NEWTON, FEINGOLD, 2007; SCHWEIGER, SCHWEIGER, SCHWEIGER, 2018; TYUVINA & NIKOLAEVSKAYA, 2019; HAMZEHGARDESHI et al., 2019; CERAN et al., 2020). However, the results found after applying the BAI instrument, identified levels of anxiety considered low, at most 06 points among the participants, with no significant difference between women and men regarding levels of anxiety. Women got an average of 04 points on the scale and men 03 points. These findings corroborate the literature found (MASSAROTTI et al., 2018; TURNER et al., 2013), as the sample received extensive emotional support during the period they were in the COVID-19 epidemic by maintaining the service in the online model. The notion of an extremely anxious group was not verified even when they were related to EBE and WHOQOL-BREF.

In this table, among the associations made, it was noteworthy that women who do not have a religion have a higher performance in the physical domain of the BREF (64.3%) compared to those who follow some creed. This fact may be related to a strengthening of marital bonds (CERAN et al., 2020; FARIA et al., 2012). Next, it is observed that women who have children produce a lower performance in the physical domain of the BREF. Our study reveals higher physical domain scores when compared with Iranian women (BAKHTIYAR, BEIRANVAND, ARDALAN, 2019). The study by Aduloju et al. (2017) points out that this lower performance in the physical domain may be related to racial issues present in Nigeria between fertile and infertile couples. The demands of motherhood may be implied in the low physical domain (JAMILIAN et al., 2017). In a study carried out in Poland (RZONCA et al., 2018), higher scores were found due to the social status of the individuals involved. This fact may be related to the possibility of building long-term plans and, therefore, interfering with greater assertiveness in the physical, social and even psychological domains.

The associations of QoL in men drew attention to the fact that men who live with other people and/or family members besides their wife have better QoL scores in the physical and psychological domains compared to those who only live with their wife. The study by Turkish researchers (ZEREN et al., 2019) corroborates that QoL is high in these cases due to marriages in which the family remains the main support for men. In this case, the family with whom the man lives in addition to the wife is observed as a social support also found in a study about infertility in Japanese couples (ASAZAWA et al., 2019). High scores in the social domain in men with lower salaries have already occurred (HUBENS et al., 2018; KOERT et al., 2019; KARACA et al., 2016; KERAMAT et al., 2014; NAMAYAR et al., 2018; SANTORO et al., 2016; STEUBER and HIGH, 2015). Men who do not work produce higher scores in the social domain, which was found in three other studies (HASSON et al., 2017; KARABULUT et al., 2017; KARABULUT, OZKAN and OGUZ, 2013). Regarding remuneration, men who earn more also have better scores in the psychological and environmental domains, as shown in a recent study (MILNER et al., 2019). Our study reveals that the current notions of the man as the provider of the couple’s earnings do not apply to all cases. Men in these cases that were not taken as expected can be thought as models of masculinity in transition (CONNELL & MESSERSCHMIDT, 2005).

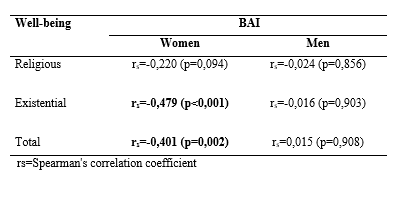

Regarding the levels of anxiety in women, interfering with existential well-being and QoL, this relationship was associated with a reduction in existential well-being (SHAHRAKI, GHAJARZADEH, GANJALI, 2019; NAMDAR et al., 2017; MONGA, 2004). The cause of infertility was a significant predictor of anxiety and distress in our sample, with higher levels in cases of female infertility. This fact is probably related to the feeling of guilt, in which personal, family, social and even religious expectations may be frustrated (LYKERIDOU et al., 2009). Such situations are typical of a feeling of religious confrontation that brings anxiety at a high level (OTI-BOADI, OPPONG ASANTE, 2017; PARGAMENT, FEUILLE, BURZY, 2011; KHALID, DAWOOD, 2020; BATNIC, LAZAREVIC, DIKIC, 2017). The fact that men do not have a religious belief has no significant association when compared to bibliographic findings (DUTNEY, 2007; HOWE et al., 2020; GRUNBERG, MINER, ZELKOWITZ, 2020).

Conclusion:

Our research raised a wide look at infertility that sometimes breaks the common sense on the subject. Thus, we showed the multiple factors that make up the problem, but one thing is certain: frustration ran through both men and women. Sometimes the impact will be minimal or even imperceptible, as having children was not a desire, however, most people will face a dilemma, exposed to stigmatizing and self-blaming conditions. The negative impact on the lives of these people cannot be disregarded (MILLER, 2003; KIM & NHO, 2020; LI et al., 2018).

We emphasize here the importance of a multidisciplinary team (WANG et al., 2020; CHOI et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018) in cases that involve both clinical issues and issues related to the psychic and emotional aspects of the subjects involved. At this point, the role of nursing in the team proved to be fundamental, providing a comprehensive look at each individual with an advice on the situation and coordination of work groups (DENNEY-KOELSC, COTÉ-ARSENAULT, 2020; CARTER, STEVENS, 2020; WAX, D ‘ANGIO, CHAFERY, 2020; IRELAND et al., 2019). Our performance in Assisted Reproduction Services should not be different from what is found in other areas of nursing practice. Identifying the problems experienced by the study population facing the experience of infertility and its confrontation mechanisms would make no sense if the main motivation to help another human being with difficulties is not the priority of the service. The issues raised here require the development of a differentiated and attentive look for each patient, thus being able to transform personal and collective realities, even improving the team’s posture.

Finally, we propose a path to increase the quality of the people served by the service. Therefore, we observe the emergence of complementary practices and therapies (BRASIL, 2015). They are not a substitute for the traditional assessment and treatment service, however, they bring an effective differential in the management of anxiogenic situations that occur in the hospital routine (CLARK et al., 2013; AVELAR & ARAÚJO, 2018). The handling of these situations is part of this work, whose purpose was headed to help a population with multiple difficulties and high expectations regarding fertility. Both men and women go through difficulties related to the topic and facing it becomes essential for the next step they will take as couples. The possibility of being united and pursuing the fertilization program is part of their human achievements towards the future. Therefore, their questions are not trivial and must be treated with great respect by the hospital’s health teams.

Tables

Table 1 – Sample characterization

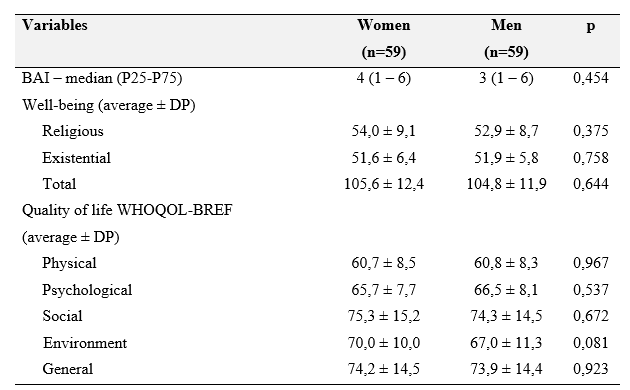

Table 2 – Data on anxiety, well-being and quality of life (BAI, EBE e WHOQOL-BREAF)

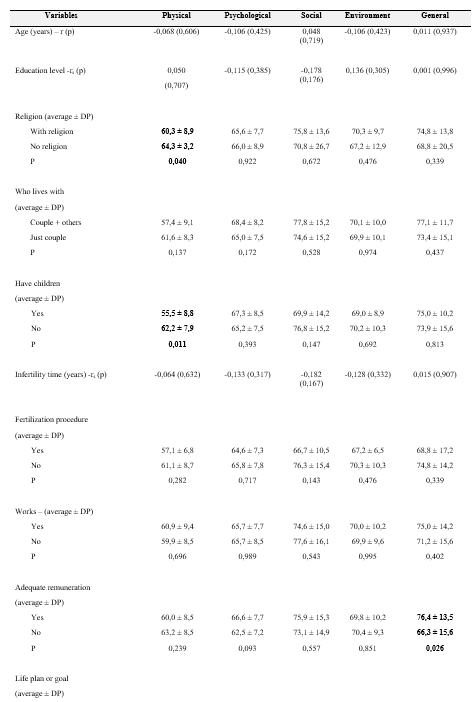

Table 3 – Associations with quality of life in women

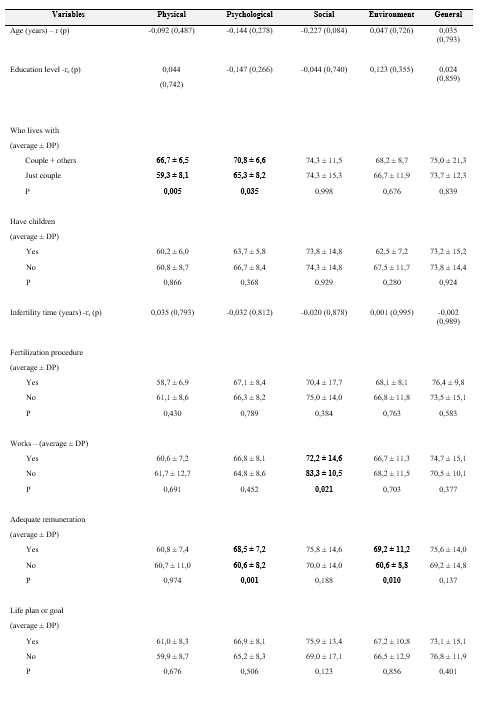

Table 4 – Associations with quality of life in men

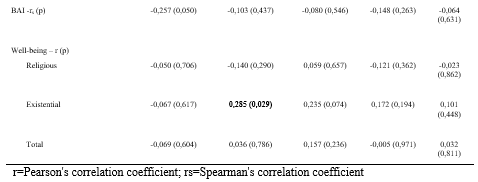

r=Pearson’s correlation coefficient; rs=Spearman’s correlation coefficient

Table 5 – Associations of anxiety levels with well-being

REFERENCES:

Agarwal, A., Mulgund, A., Hamada, A., & Chyatte, M. R. (2015). A unique view on male infertility around the globe. Reproductive biology and endocrinology, 13(1), 1-9.

Asazawa, K., Jitsuzaki, M., Mori, A., Ichikawa, T., Shinozaki, K., & Porter, S. E. (2019). Quality‐of‐life predictors for men undergoing infertility treatment in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 16(3), 329-341.

Avelar, C. C. & Araújo, C. Terapias Complementares. In: Avelar, C. C. & Caetano, J. P. J. Psicologia em Reprodução Humana. São Paulo: SBRH, 2018.

Babakhanzadeh, E., Nazari, M., Ghasemifar, S., & Khodadadian, A. (2020). Some of the factors involved in male infertility: a prospective review. International journal of general medicine, 13, 29.

Bakhtiyar, K., Beiranvand, R., Ardalan, A., Changaee, F., Almasian, M., Badrizadeh, A., … & Ebrahimzadeh, F. (2019). An investigation of the effects of infertility on Women’s quality of life: a case-control study. BMC women’s health, 19(1), 1-9.

Baptista, M. N., & Carneiro, A. M. (2011). Validade da escala de depressão: relação com ansiedade e stress laboral. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 28(3), 345-352.

Batinic, B., Lazarevic, J., & Dragojevic-Dikic, S. (2017). Correlation between self-efficacy and well-being, and distress, in women with unexplained infertility. European Psychiatry, 41(S1), s899-s899.

Benyamini, Y., Gozlan, M., & Weissman, A. (2017). Normalization as a strategy for maintaining quality of life while coping with infertility in a pronatalist culture. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24(6), 871-879.

Brasil (2015). Ministério da Saúde. PNPIC: Política Nacional de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares no SUS. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde.

Carter, R. & Stevens, B. Genetics and Genetic Counseling in Perinatal Palliative Care. IN: Denney-Koelsch, E. M., & Coté-Arsenaut, D. (2020). Perinatal Palliative Care.

Ceran, M. U., Yilmaz, N., Ugurlu, E. N., Erkal, N., Ozgu-Erdinc, A. S., Tasci, Y., … & Engin-Ustun, Y. (2020). Psychological domain of quality of life, depression and anxiety levels in in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles of women with endometriosis: A prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1-8.

Chachamovich, J. L. R. (2009). Qualidade de vida em infertilidade: revisão sistemática dos achados da literatura e avanços na investigação de homens e casais inférteis.

Choi, C. Y., Cho, N. J., Park, S., Gil, H. W., Kim, Y. S., & Lee, E. Y. (2018). A case report of successful pregnancy and delivery after peritoneal dialysis in a patient misdiagnosed with primary infertility. Medicine, 97(26).

Clark, N. A., Will, M., Moravek, M. B., & Fisseha, S. (2013). A systematic review of the evidence for complementary and alternative medicine in infertility. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 122(3), 202-206.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & society, 19(6), 829-859.

Cunha, M. D. C. V. D., Carvalho, J. A., Albuquerque, R. M., Ludermir, A. B., & Novaes, M. (2008). Infertilidade: associação com transtornos mentais comuns e a importância do apoio social. Revista de Psiquiatria do Rio Grande do Sul, 30, 201-210.

Dantas, R. A. S., Sawada, N. O., & Malerbo, M. B. (2003). Pesquisas sobre qualidade de vida: revisão da produção científica das universidades públicas do Estado de São Paulo. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 11, 532-538.

Denney-Koelsch, E. M., & Côté-Arsenault, D. (2020). Perinatal Palliative Care. Springer International Publishing.

Direkvand-Moghadam, A., Delpisheh, A., & Direkvand-Moghadam, A. (2015). Effect of infertility on sexual function: a cross-sectional study. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 9(5), QC01.

Dutney, A. (2007). Religion, infertility and assisted reproductive technology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21(1), 169-180.

Dyer, S. J., Abrahams, N., Mokoena, N. E., Lombard, C. J., & van der Spuy, Z. M. (2005). Psychological distress among women suffering from couple infertility in South Africa: a quantitative assessment. Human reproduction, 20(7), 1938-1943.

Farinati, D. M., Rigoni, M. D. S., & Müller, M. C. (2006). Infertilidade: um novo campo da psicologia da saúde. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 23, 433-439.

Faria, D. E. P. D., Grieco, S. C., & Barros, S. M. O. D. (2012). Efeitos da infertilidade no relacionamento dos cônjuges. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 46, 794-801.

Fleck, M., Louzada, S., Xavier, M., Chachamovich, E., Vieira, G., Santos, L., & Pinzon, V. (2000). Aplicação da versão em português do instrumento abreviado de avaliação da qualidade de vida” WHOQOL-bref”. Revista de saúde pública, 34, 178-183.

Grunberg, P., Miner, S., & Zelkowitz, P. (2020). Infertility and perceived stress: the role of identity concern in treatment-seeking men and women. Human fertility, 1-11.

Hamzehgardeshi, Z., Yazdani, F., Elyasi, F., Moosazadeh, M., Peyvandi, S., & Samadaee, K. (2019). Investigating the mental health status of infertile women. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine, 17(4), 293-294.

Hasson, J., Tulandi, T., Shavit, T., Shaulov, T., Seccareccia, E., & Takefman, J. (2017). Quality of life of immigrant and non‐immigrant infertile patients in a publicly funded in vitro fertilisation program: a cross‐sectional study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 124(12), 1841-1847.

Helman, C. G. (1994). Cultura, saúde e doença. Artmed Editora.

Howe, S., Zulu, J. M., Boivin, J., & GerriTS, T. (2020). The social and cultural meanings of infertility for men and women in Zambia: legacy, family and divine intervention. Facts, views & vision in ObGyn, 12(3), 185.

Hubens, K., Arons, A. M., & Krol, M. (2018). Measurement and evaluation of quality of life and well-being in individuals having or having had fertility problems: a systematic review. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 23(6), 441-450.

Ilska, M., Brandt-Salmeri, A., & Kołodziej-Zaleska, A. (2020). Effect of prenatal distress on subjective happiness in pregnant women: The role of prenatal attitudes towards maternity and ego-resiliency. Personality and Individual Differences, 163, 110098.

Inhorn, M. C., & Patrizio, P. (2015). Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Human reproduction update, 21(4), 411-426.

Ireland, S., Ray, R. A., Larkins, S., & Woodward, L. (2019). Perspectives of time: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents of critically ill newborns in the neonatal nursery in North Queensland interviewed several years after the admission. BMJ open, 9(5), e026344.

Jahromi, B. N., Mansouri, M., Forouhari, S., Poordast, T., & Salehi, A. (2018). Quality of life and its influencing factors of couples referred to an infertility center in Shiraz, Iran. International journal of fertility & sterility, 11(4), 293.

Jamilian, H., Jamilian, M., & Soltany, S. (2017). The Comparison of Quality Of Life and Social Support among Fertile and Infertile Women. Journal of Patient Safety & Quality Improvement, 5(2), 521-525.

Jodeiryzaer, S., Farsimadan, M., Abiri, A., Sharafshah, A., & Vaziri, H. (2020). Association of oestrogen receptor alpha gene SNPs Arg157Ter C> T and Val364Glu T> A with female infertility. British journal of biomedical science, 77(4), 216-218.

Karabulut, A., Demirtaş, Ö., Sönmez, S., Karaca, N., & Gök, S. (2017). Assessing factors associated with infertility using a couple-based approach.

Karabulut, A., Özkan, S., & Oğuz, N. (2013). Predictors of fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) in infertile women: analysis of confounding factors. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 170(1), 193-197.

Karaca, N., Karabulut, A., Ozkan, S., Aktun, H., Orengul, F., Yilmaz, R., … & Batmaz, G. (2016). Effect of IVF failure on quality of life and emotional status in infertile couples. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 206, 158-163.

Keramat, A., Masoomi, S. Z., Mousavi, S. A., Poorolajal, J., Shobeiri, F., & Hazavhei, S. M. M. (2013). Quality of life and its related factors in infertile couples. Journal of research in health sciences, 14(1), 57-64.

Khalid, A., & Dawood, S. (2020). Social support, self-efficacy, cognitive coping and psychological distress in infertile women. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 302, 423-430.

Kim, Y. M., & Nho, J. H. (2020). Factors influencing infertility-related quality of life in infertile women. Korean Journal of Women Health Nursing, 26(1), 49-60.

Koert, E., Takefman, J., & Boivin, J. (2021). Fertility quality of life tool: update on research and practice considerations. Human Fertility, 24(4), 236-248.

Leão, J. A. C. K., & Lindôso, Z. C. L. Infertilidade feminina: aspectos multidimensionais e a percepção da mulher/Female Infertility: multidimensional aspects and the woman’s perception. Revista Interinstitucional Brasileira de Terapia Ocupacional-REVISBRATO, 4(6), 985-1003.

Li, J., Li, J., Jiang, S., Yu, R., & Yu, Y. (2018). Case report of a pituitary thyrotropin-secreting macroadenoma with Hashimoto thyroiditis and infertility. Medicine, 97(1).

Lloyd, C. B. (1991). The contribution of the World Fertility Surveys to an understanding of the relationship between women’s work and fertility. Studies in family planning, 22(3), 144-161.

Lykeridou, K., Gourounti, K., Deltsidou, A., Loutradis, D., & Vaslamatzis, G. (2009). The impact of infertility diagnosis on psychological status of women undergoing fertility treatment. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 27(3), 223-237.

Marques, L. F., Sarriera, J. C., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2009). Adaptação e validação da Escala de Bem-estar Espiritual (EBE): Adaptation and validation of Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWS). Avaliaçao Psicologica: Interamerican Journal of Psychological Assessment, 8(2), 179-186.

Massarotti, C., Gentile, G., Ferreccio, C., Scaruffi, P., Remorgida, V., & Anserini, P. (2019). Impact of infertility and infertility treatments on quality of life and levels of anxiety and depression in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Gynecological Endocrinology, 35(6), 485-489.

McCarthy, H. (2020). Double Lives: A History of Working Motherhood. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Miller, J. Mourning the never born and the loss of the Angel (2003). In: Haynes, J.; Moller , J. (Org.). Inconceivable Conceptions: Psychological aspects of infertility and reproductive technology. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Miner, S. A., Daumler, D., Chan, P., Gupta, A., Lo, K., & Zelkowitz, P. (2019). Masculinity, mental health, and desire for social support among male cancer and infertility patients. American journal of men’s health, 13(1), 1557988318820396.

Monga, M., Alexandrescu, B., Katz, S. E., Stein, M., & Ganiats, T. (2004). Impact of infertility on quality of life, marital adjustment, and sexual function. Urology, 63(1), 126-130.

Namdar, A., Naghizadeh, M. M., Zamani, M., Yaghmaei, F., & Sameni, M. H. (2017). Quality of life and general health of infertile women. Health and Quality of life Outcomes, 15(1), 1-7.

Oti-Boadi, M., & Oppong Asante, K. (2017). Psychological health and religious coping of Ghanaian women with infertility. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 11(1), 1-7.

Pargament, K., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2(1), 51-76.

Passos, E (2017). Infertilidade. In: Freitas, F. Rotinas em ginecologia, 7.

Peterson, B. D., Newton, C. R., & Feingold, T. (2007). Anxiety and sexual stress in men and women undergoing infertility treatment. Fertility and sterility, 88(4), 911-914.

Piccinini, C. A., Lopes, R. S., Gomes, A. G., & De Nardi, T. (2008). Gestação e a constituição da maternidade. Psicologia em estudo, 13, 63-72.

Ramezanzadeh, F., Aghssa, M. M., Abedinia, N., Zayeri, F., Khanafshar, N., Shariat, M., & Jafarabadi, M. (2004). A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC women’s health, 4(1), 1-7.

Rzońca, E., Bień, A., Wdowiak, A., Szymański, R., & Iwanowicz-Palus, G. (2018). Determinants of quality of life and satisfaction with life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(2), 376.

Santoro, N., Eisenberg, E., Trussell, J. C., Craig, L. B., Gracia, C., Huang, H., … & Zhang, H. (2016). Fertility-related quality of life from two RCT cohorts with infertility: unexplained infertility and polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction, 31(10), 2268-2279.

Santos, B., Silveira, B., Dias, H., & Coutinho, E. (2020). As medidas utilizadas para avaliar o nível emocional da família perante a infertilidade: uma scoping review. Revista da UI_IPSantarém-Unidade de Investigação do Instituto Politécnico de Santarém, 8(1), 343-357.

Santos, T. S. M. (2019). A MATERNIDADE, A MULHER E A HISTÓRIA. In Congresso Brasileiro de Assistentes Sociais, 16(1).

Schweiger, U., Schweiger, J. U., & Schweiger, J. I. (2018). Mental disorders and female infertility. Archives of Psychology, 2(6).

Shahraki, Z., Ghajarzadeh, M., & Ganjali, M. (2019). Depression, anxiety, quality of life and sexual dysfunction in Zabol women with infertility. Mædica, 14(2), 131.

Siristatidis, C., Pouliakis, A., & Sergentanis, T. N. (2020). Special characteristics, reproductive, and clinical profile of women with unexplained infertility versus other causes of infertility: A comparative study. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 37, 1923-1930.

Steuber, K. R., & High, A. (2015). Disclosure strategies, social support, and quality of life in infertile women. Human Reproduction, 30(7), 1635-1642.

Turner, K., Reynolds-May, M. F., Zitek, E. M., Tisdale, R. L., Carlisle, A. B., & Westphal, L. M. (2013). Stress and anxiety scores in first and repeat IVF cycles: a pilot study. PloS one, 8(5), e63743.

Tyuvina, N. A., & Nikolaevskaya, A. O. (2019). Infertility and mental disorders in women. Communication 1. Neurology, Neuropsychiatry, Psychosomatics, 11(4), 117-124.

Wang, R., Chen, Z. J., Vuong, L. N., Legro, R. S., Mol, B. W., & Wilkinson, J. (2020). Large randomized controlled trials in infertility. Fertility and sterility, 113(6), 1093-1099.

Wax, J. W.; D’angio, C. T. & Chafery, M. C. Perinatal Ethics. IN: Denney-Koelsch, E. M., & Coté-Arsenault, D. (Eds.). Perinatal Palliative Care, 2020.

Vázquez, G. G. H. (2018). Imperfeições no papel: a infertilidade nas páginas da Revista Pais & Filhos. Revista Estudos Feministas, 26.

Záchia, S. D. A. (2006). A visão dos profissionais da saúde na abordagem de questões de reprodução assistida: uma perspectiva transcultural.

Zeren, F., Gürsoy, E., & Çolak, E. (2019). The quality of life and dyadic adjustment of couples receiving infertility treatment. African journal of reproductive health, 23(1), 117-127.

¹ Posgraduate Program in Gynecology and Obstetrics, School of Medicine, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

² Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

³ School of Medicine, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Full names: Laiza Simone Garcia Quadro; Andressa da Silva Behenck; Suzana de Azevedo Zachia; Flávia Sarvacinski; Cristiana Palma Kuhl; Markus Berger; Eduardo Pandolfi Passos; Paula Barros Terraciano.

*Corresponding author: Laiza Simone Garcia Quadro address: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics – Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2350, 90035-903, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. Phone: +55 51 981772235

E-mail addresses: laizaquadro@hotmail.com