REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10950686

Dinara de Morais Gouveia1;

Otenberg Nogueira de Souza Junior2

ABSTRACT

Introduction:. Sexual violence is a significant public health issue. With the goal of reducing these adverse health events and minimizing episodes of sexual violence in the global population, particularly in Brazil, numerous scholars have begun to research the short- and long-term effects of health education on sexual quality, rates of sexual assault, sexual harassment, that is, on sexual violence. Aim: To demonstrate the effect of health education on the prevention of sexual violence through a systematic review. Methods: Systematic review, following the PRISMA flow diagram, including articles available in all languages, regardless of publication date, using the PICO strategy. A total of 2,544 articles were searched between February and May 2023, through databases such as CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, Open Science Journal, PeDro, PubMed, Scielo, Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, and OpenGrey. The “StArt” Systematic Review manager was used to eliminate duplicate articles. The Rob 2.0 tool was employed to assess the methodological quality and evaluate the risk of bias in randomized clinical trial studies. Results: This systematic review included 10 out of 16 studies, focusing on the effectiveness of health education interventions in preventing sexual violence. The studies, varying in design and participant demographics, involved diverse educational strategies targeting sexual violence and education. Results indicated that these interventions could effectively improve knowledge and reduce incidents of sexual violence across different groups, including adolescents, pregnant women, nurses, and midwives. However, one study showed no positive outcomes, underscoring the importance of methodological quality in evaluating intervention success. Conclusion: The review highlights the effectiveness of diverse educational approaches—whether individual, group, in-person, or online—in shaping attitudes and behaviors towards sexual conduct and diminishing sexual violence. Interactive discussions, media use, and online tools particularly boost participation and knowledge application.

Keywords: Health education; Sexual violence; public health.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) to be achieved by 2030 is sexual health (ALIZADEH et al., 2021), as the quality of sexual life is paramount to overall quality of life, given the inclusion of a range of attributes related to sexual, psychological, emotional interactions, and sexual satisfaction with oneself and one’s partner (TSAI; YEH; HWANG, 2011).

When sexual acts are not agreed upon, allowed, or desired, using physical force or subject to humiliation, sexual harassment, or aggression during sexual relations, they are considered sexual violence (ALIZADEH et al., 2021; MENNICKE et al., 2022), or when the victim is incapable of consenting or refusing the sexual act (ANGELONE et al., 2022).

Although men can suffer sexual violence, women are the ones who most report having experienced or are experiencing it, accounting for about 44% (SMITH et al., 2018).

Sexual violence often occurs in conjunction with another form of violence such as psychological, financial, stalking, among others (WILKINS N et al., 2014). Mennicke et al., 2022, state that the prevalence of sexual assault, stalking, and sexual harassment has been growing exponentially among high school students. Additionally, (Smith et al., 2018) report that the risk is heightened among youths who witnessed intimate partner violence, with potential perpetrators being relatives, friends, romantic partners, college youths, acquaintances, and strangers (BASILE, KC; SMITH, SG; BREIDING, MJ; BLACK, MC AND MAHENDRA, RR (2014).

Thus, these victims may suffer negative consequences such as depression, anxiety, sleep and eating disorders, and substance use, among others (SMITH., 2018).

Sexual violence is a significant public health issue. With the aim of reducing these adverse health events and minimizing episodes of sexual violence in the global population, especially in Brazil, numerous scholars have begun to research the short- and long-term effects of health education on sexual quality, rates of sexual aggression, sexual harassment, that is, on sexual violence.

Health education, especially sexual intervention, has been an option used to improve sexual problems and couple conflicts. It is known that to achieve the desired sexual health, acquiring knowledge and awareness of the dimensions of sexuality is necessary, and that sexual literacy increases an individual’s ability to analyze, judge, discuss, make decisions, and change sexual behavior, i.e., education and sexual counseling significantly improves sexual health (JANGI et al., 2021).

The hypothesis of this study is that health education prevents sexual violence in the Brazilian population, improving their quality of life.

There are several studies addressing health education as prevention of sexual violence, however, there is no systematic review that compiles this information showing the effects of sexual education and the types of educational modalities used, making this research unprecedented in Brazil. Thus, this systematic review will be relevant for health professionals working in Primary Health Care, as it will serve as a guide in choosing the educational modality, as well as helping to act specifically for each minority group and age groups. Moreover, it will serve as educational support for the population and academics in informing and appropriately addressing the theme.

Therefore, this systematic review aims to highlight the effect of health education on the prevention of sexual violence.

2 METHODS

Study design

Systematic review (SR) following the flowchart of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA), including randomized and cluster randomized trials. This review is registered on the PROSPERO platform with ID CRD42021247918.

Inclusion criteria

Articles available in all languages, regardless of publication date, given that this is the first review addressing the theme. A total of 2,544 articles were searched from February to May 2023, through databases such as Medline, PubMed, Scielo, Web of Science, Science Direct, and EMBASE. The articles encompass relevant information for health professionals on the repercussions of sexual education in the prevention of sexual violence.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if the title or abstract did not contain the keywords, as well as studies with incomplete abstracts or those lacking well-defined methods and conclusions. Additionally, works that did not clearly delineate the guiding research question and duplicate articles were also excluded.

Study Protocol

PICO and search strategy

The PICO strategy (P – population; I – intervention; C – comparison; O – outcomes; S – Study) (Table 1) guided the formulation of the guiding question for the SR and served as the basis for developing search strategies using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) descriptors and the Boolean operators AND and OR, as presented in Table 2. Thus, the research questions were: “Does health education prevent sexual violence? What educational modalities are used for the prevention of sexual violence?”.

Table 1. Elements of the PICO strategy, descriptors, and keywords, Brazil, 2023.

Component Definition Descriptors Keywords P: Population of interest People who have experienced sexual violence or not Sexual offenses; sexual violence; violence against women; sexual harassment; rape. Sex offenses; sexual violence; violence against women; sexual harassment; rape. I: Intervention Health Education Health education; Health education. C: Comparison – – – O: Outcome Prevention of violence; Quality of life; Sexual function; Rates of sexual violence Quality of life; sexual behavior. Quality of life; sexual behavior. S: Study type Randomized controlled trial Randomized controlled trial Randomized controlled trial

Source: Gouveia et al., 2023.

In it, the first element of the strategy (P) consists of people who have or have not suffered sexual violence; the second element (I) Health Education, while the third element (C) of the PICOS strategy was not added, and the fourth element (O) corresponds to violence prevention; Quality of life; Sexual function; Rates of sexual violence. The searches were conducted using the following search strategy described in Table 2.

Table 2: Search strategies used in the databases, Piauí, Brazil, 2023.

DatabasesOnline library “Search Strategies” Medline (health education) AND (sexual violence)”Filters: full text; randomized clinical trial” Pubmed (health education) AND (sexual violence)”Filters: full text; randomized clinical trial” Scielo (health education) AND (sexual violence)”Filter: literature type (article)” Web of Science (health education) AND (sexual violence) OR (sex offenses)”Filter: open access; study type: article” Science Direct (health education) AND (sexual violence) OR (sex offenses)”Filter: research article” EMBASE (health education) AND (sexual violence) OR (sexual offenses) OR (violence against women)”Filters: by title and abstract; randomized clinical trial”

Source: Gouveia et al., 2023.

Article selection

Initially, titles were analyzed, followed by abstract reading to identify those to be fully evaluated. After reading, the works were selected for methodological quality assessment; finally, those meeting well-established criteria were included in the study’s final sample. The required data were then extracted using an instrument containing identification information (authors and year), population, interventions, and outcomes/conclusions.

Assessment of methodological quality and risk of bias in studies

The methodological quality of the clinical trials was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2.0) and its additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials, which assesses five domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in outcome measurement; (5) bias in selection of the reported result, as presented in Table 3. The additional part of RoB 2.0 for cluster-randomized trials considers six domains: (1) risk of bias arising from the process of randomization in a cluster-randomized trial; (2) risk of bias due to timing of identification or recruitment of participants; (3) bias due to deviations from intended intervention (compliance); (4) bias due to deviations from intervention (compliance); (5) risk of bias due to missing outcome data; (6) risk of bias in outcome measurement; (7) risk of bias in selection of reported results, as shown in Table 4. Studies with high risk of bias in more than one domain were excluded to avoid compromising the interpretation of results.

Table 3. Assessment of methodological quality according to Risk of Bias 2.0 for randomized clinical trials, Piauí, Brazil, 2023.

Reference D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 Overall Gurkan OC; Kumurcu N (2017) Kesler K, et al. (2023) Salazar LF, et al. (2014) Scull TM, et al. (2022) Urbann K; Bienstein P; Kaul T (2020) Yount KM, et al. (2023)

Caption: D1= Randomization process; D2= Deviations from intended interventions; D3= Missing outcome data; D4= Outcome measurement; D5= Selection of reported outcome;= Low risk of bias;

= Some considerations;

= High risk of bias.

Source: Gouveia et al., 2023.

Table 4. Assessment of methodological quality according to Risk of Bias 2.0 for cluster-randomized clinical trials, Piauí, Brazil, 2023.

Reference D1 D2 D3 D4 D5 D6 D7 Alizadeh S et al. (2021) Kostu N; Toraman AU (2021) Lijster GPA et al. (2016) Miller E et al. (2015) Miller E et al. (2020)

Legend: D1= risk of bias due to the randomization process; D2= risk of bias due to timing of participant identification or recruitment; D3= bias due to deviations from intended intervention (allocation); D4= bias due to deviations from intervention (compliance); D5= risk of bias due to missing outcome data; D6= risk of bias in outcome measurement; D7= risk of bias in selection of reported results.= Low risk of bias;

= Some considerations;

= High risk of bias.

Source: Gouveia et al., 2023.

Analysis of results

After thorough review, the data from the studies included in this systematic review were analyzed and presented descriptively in a table with author and year details, sample size and population, intervention, intervention strategies, outcomes, and conclusions. Meta-analysis was not possible due to the number of articles in the final sample.

3 RESULTS

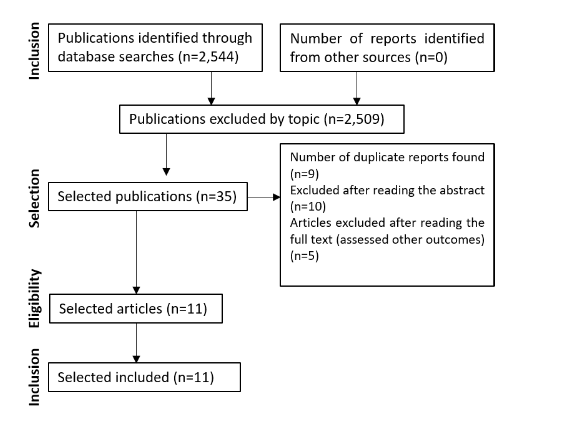

Based on the search strategies and selection presented in the methods section, 16 studies were included for full-text reading, of which 10 comprised the final sample. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study selection process, Brazil, 2023.

Souce: Gouveia et al., 2023.

Six randomized clinical trials and five cluster-randomized clinical trials were selected, however, the study by Kesler et al. (2023) did not meet the methodological quality criteria and was excluded from the final sample. The studies by Urbann et al. (2020) and Miller et al. (2020) were the only ones that presented at least one domain with a high risk of bias. The studies by Salazar et al. (2014) and Yount et al. (2020) showed low risk of bias in all evaluated domains. Most of the other studies had a low risk of bias in at least two assessment domains, thus being included in this research.

The sample characteristics are diverse, as the number of evaluated participants ranges from 92 to 2,291, totaling 6,724 volunteers overall. Based on gender data, women account for 51.79% (n=3,483), men for 45.70% (n=3,073), and other genders or unclassified represent 2.49% (168). The mean age is 17.85 years, calculated based on studies providing such data as the mean across their groups. The individuals included in the studies are diverse, tailored to the objective of each research, but mostly consist of high school students, followed by pregnant women, nurses, and midwives. The intervention duration is not well explained in all studies to compute an average, but it ranges from days, weeks, and months, as well as an intervention conducted throughout an entire school year. The professionals who implemented the interventions underwent some form of training, as well as training on assessment instruments. The characterization of the studies is presented in Appendix A.

The interventions vary in terms of audience, objectives, and application strategies. Samples were conducted through randomization and clusters, thus each group was allocated to an intervention or even to a control group without a specific experiment. The predominant topics in most studies are related to sexual violence and sexual education with knowledge about the subject, addressed in online or face-to-face formats, with educational tools through case discussions, content presentations, media content, and others. Strategies occurred individually or in groups, with self-applied knowledge or through someone selected by the research sponsors.

The programs or interventions in the experimental groups showed effectiveness in most of their outcomes, revealing that various health education strategies are applicable within the topic of sexual violence. However, the study by Miller et al. (2020) did not yield positive conclusions regarding its outcomes. They developed a program to provide education on sexual violence and discussed harm reduction behavior during visits to health centers and counseling. This study, in turn, presented “some considerations” within the methodological evaluation by Risk Of Bias 2.0 in four domains, and high risk of bias in the selection of the presented results.

On another note, sexual health education can improve key domains of sexual health and reduce sexual violence during pregnancy. The study by Alizadeh et al. (2021) reveals that 90-minute sessions in each trimester of pregnancy addressing content on anatomy, sexual physiology, physiological changes during pregnancy, and knowledge about sexual violence improve responses regarding sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction.

It is noteworthy that knowledge about intimate partner violence can be addressed by nurses and midwives during their practices and help women reduce this index of violence. The study by Kostu and Toraman (2022) addresses training based on the Theory of Planned Behavior for nurses and midwives through PowerPoint presentations, film projections, case studies, dramatizations, and debates. This type of training was effective in improving the practices of nurses and midwives regarding domestic violence against women and supporting reporting.

These trainings and workshops are essential, as highlighted in the findings of Gürkan and Kömürcü (2017) where they introduced a program for combating violence against women for nursing students. Through computer presentations, training videos, group activities, and case studies over five days, they revealed an improvement in knowledge and attitudes regarding violence against women, as well as the ability to explain correct interventions in case studies.

Health education strategies conducted with adolescents showed positive outcomes in reducing sexual harassment behaviors. The investigation by Lijster et al. (2016) had these results with an intervention divided into elements such as introductory class, educational theater play, conducted group discussion, and lessons to teach social and sexual behavior skills. Miller et al. (2015) also analyzed these outcomes and adopted an evidence-based intervention program to prevent both dating violence and sexual coercion among adolescents. They used an approach with counseling sessions and discussions about relationships and strategies for dealing with abuse, and showed positive changes in their objectives.

Online tools introduce a new approach to education and adherence among adolescents, as evidenced by the study by Scull et al. (2022) with a sexual health education intervention based on media. The program adopted topics with online classes such as gender role stereotypes, dating violence, transmission and prevention of sexually transmitted infections, as well as effective communication about sexual health, with positive results on sexual health knowledge, reduction in risky sexual behaviors.

Online platforms were adopted for research in the studies by Salazar et al. (2014) and Yount et al. (2020) with groups of heterosexual or bisexual men. Both interventions aim to prevent sexually violent behaviors and promote prosocial behaviors through online modules in a didactic and interactive way. They showed positive results such as lower likelihood of engaging in sexually violent behaviors, as well as significant reduction in perpetration of sexual violence.

A more focused audience was analyzed by Urbann et al. (2020) who studied an intervention in groups of deaf and hard of hearing children with a sexual abuse prevention program. The study included interactive activities and group discussions with elements of knowledge about the human body, feelings, touches, and strategies for seeking help, and was effective in improving children’s knowledge about sexual abuse prevention.

4 DISCUSSION

This study sought evidence regarding the effectiveness of health education in preventing sexual violence, describing the main strategies used within the applied interventions. Solange L; Abbate (1994) describes health education as a field of practices that occur at the level of social relationships usually established by health professionals, among themselves, with institutions, and especially with the user, in the daily development of their practices. In this way, techniques and methods can be adopted to guide about some risky behavior and promote skills and attitudes to ensure quality of life (Stotz, 1993).

Qualifying health professionals is a strategy to contribute to the improvement of care for victims of sexual violence, as the acquired knowledge can contribute to assist in a qualified and humanized manner (Moreira et al., 2018). Thus did Gürkan and Kömürcü (2017) with a training program for nursing students, where they managed to improve their knowledge and attitudes about violence against women. The need for the application of this type of training arises from the perception of the students themselves about the theme. Sobrinho and colleagues (2019) investigated that these students consider gender violence as a public health problem that needs to be addressed in their training.

In professional practice, training strategies can also adapt to the theme of sexual violence by intimate partners so that nurses and midwives can apply them during their home visits. Kostu and Toraman (2022) used active methodologies for this type of training and provided participants with more confidence through health education regarding domestic violence. According to Mascarenhas et al., 2020, notifications of intimate partner violence against women in Brazil are predominantly physical abuse (86.6%), followed by psychological (53.1%) and sexual (4.8%). Another study, conducted in Maranhão (Brazil), identified that during pregnancy, isolated psychological violence is more frequent (18.9%) (Da Conceição; Coelho; Madeiro, 2021). These data underscore the importance of professionals’ competence during home visits.

Health education intervenes in sexual function and reduction of sexual violence during pregnancy. Based on this, contents about health carried out in each trimester led to an improvement in responses regarding sexual desire and satisfaction in an investigation carried out by Alizadeh et al. (2021). Dos Santos et al. (2021) support these findings, affirming that health education can help women at any stage of life improve their sexual function through sexual health knowledge and skills development to address sexuality issues.

Health education strategies with adolescents are diverse, as they aim to improve intervention adherence and skill development. Lijster et al. (2016), Miller et al. (2015) applied various methodologies in young people to reduce sexual harassment behaviors and both showed positive results on their outcomes. Using online tools alone or in combination with other means, the investigations by Scull et al. (2022), Salazar et al. (2014), and Yount et al. (2020) verified their effectiveness in reducing risky sexual behaviors and sexual health knowledge of adolescents.

According to Vasconcelos, Grillo, and Soares (2018), health education practices should consider the characteristics of the individuals and groups involved. The studies presented incorporated active methodologies for the educational process within each theme, and few of them used resources in isolation. It is observed that online discussions and content showed efficacy on outcomes of sexual violence, behaviors, or knowledge about sexuality. Studies that were not included had a methodology that did not fit the objectives of this research.

The study limitations were due to the lack of methodological specificity on the theme. Findings characterizing some educational strategy and sexual violence are still scarce, as are outcomes on sexual health domains and reduction of violence rates. Another limiting factor is the homogeneity in the study populations, as clinical trials with specific audiences are limited or have low methodological quality. The final results focus on various active educational methodologies on gender violence, behaviors, skills, and attitudes, applicable mainly to students.

5 CONCLUSION

This review identified that the combination of different educational methodologies provided individually or in groups, in-person or online, is effective for developing skills and attitudes regarding sexual behavior and reducing sexual violence. Activities involving discussion, media, interactivity with online tools facilitate adherence and contribute to the practical application of knowledge.

REFERENCES

ALIZADEH, S. et al. The effect of sexual health education on sexual activity, sexual quality of life, and sexual violence in pregnancy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, v. 21, n. 1, 1 dez. 2021.

(BASILE, K. S. S. B. M. B. M. E M. R. SEXUAL VIOLENCE SURVEILLANCE: UNIFORM DEFINITIONS AND RECOMMENDED DATA ELEMENTS VERSION 2.0. [s.l: s.n.].

COSTA, N. et al. ARTIGO ORIGINAL Violência contra a mulher: a percepção dos graduandos de enfermagem Violence against women: how nursing students perceive it Violencia contra la mujer: la percepción de estudiantes de enfermería. [s.l: s.n.]. Disponível em: <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5391-4362>.

DA CONCEIÇÃO, H. N.; COELHO, S. F.; MADEIRO, A. P. Prevalence and factors associated with intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Caxias, state of Maranhão, Brazil, 2019-2020*. Epidemiologia e Servicos de Saude, v. 30, n. 2, 2021.

DE LIJSTER, G. P. A. et al. Effects of an Interactive School-Based Program for Preventing Adolescent Sexual Harassment: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Evaluation Study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, v. 45, n. 5, p. 874–886, 1 maio 2016.

DOS SANTOS, P. P. et al. Práticas de educação em saúde voltadas para função sexual feminina. Revista Eletrônica Acervo Saúde, v. 13, n. 4, p. e6708, 7 abr. 2021.

GÜRKAN, Ö. C.; KÖMÜRCÜ, N. The effect of a peer education program on combating violence against women: A randomized controlled study. Nurse Education Today, v. 57, p. 47–53, 1 out. 2017.

KESLER, K. et al. High School FLASH Sexual Health Education Curriculum: LGBTQ Inclusivity Strategies Reduce Homophobia and Transphobia. Prevention Science, v. 24, p. 272–282, 1 dez. 2023.

KOŞTU, N.; TORAMAN, A. U. The Effect of an Intimate Partner Violence Against Women Training Program Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior on the Approaches of Nurses and Midwives: A Randomized Controlled Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, v. 37, n. 17–18, p. NP16157–NP16179, 1 set. 2022.

MASCARENHAS, M. D. M. et al. Analysis of notifications of intimate partner violence against women, Brazil, 2011-2017. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, v. 23, p. 1–13, 2020.

MILLER, E. et al. A School Health Center Intervention for Abusive Adolescent Relationships: A Cluster RCTPEDIATRICS. [s.l: s.n.].

MILLER, E. et al. Cluster Randomized Trial of a College Health Center Sexual Violence Intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, v. 59, n. 1, p. 98–108, 1 jul. 2020.

MOREIRA, G. A. R. et al. QUALIFICAÇÃO DE PROFISSIONAIS DA SAÚDE PARA A ATENÇÃO ÀS MULHERES EM SITUAÇÃO DE VIOLÊNCIA SEXUAL. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde, v. 16, n. 3, p. 1039–1055, 13 ago. 2018.

SALAZAR, L. F. et al. A web-based sexual violence bystander intervention for male college students: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, v. 16, n. 9, 1 set. 2014.

SCULL, T. M. et al. A Media Literacy Education Approach to High School Sexual Health Education: Immediate Effects of Media Aware on Adolescents’ Media, Sexual Health, and Communication Outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, v. 51, n. 4, p. 708–723, 1 abr. 2022.

SMITH S, Z. X. B. K. ET AL. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief — Updated Release. [s.l: s.n.].

SOLANGE L; ABBATE. Educação em Saúde: uma Nova Abordagem Health Education: A New Approach. [s.l: s.n.].

STOTZ, E. N. ENFOQUES SOBRE EDUCAÇÃO E SAÚDE. [s.l: s.n.].

TSAI, T.-F.; YEH, C.-H.; HWANG, T. I. S. Female Sexual Dysfunction: Physiology, Epidemiology, Classification, Evaluation and Treatment. Urological Science, v. 22, n. 1, p. 7–13, mar. 2011.

URBANN, K.; BIENSTEIN, P.; KAUL, T. The evidence-based sexual abuse prevention program: Strong with sam. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, v. 25, n. 4, p. 421–429, 1 out. 2020.

VASCONCELOS, M. et al. Práticas educativas e tecnologias em saúde. [s.l: s.n.].

WILKINS N, T. B. H. M. D. R. K. J. Connecting the Dots: An Overview of the Links Among Multiple Forms of Violence Prevention and equity at the center of community well-being. [s.l: s.n.].

YOUNT, K. M. et al. Preventing sexual violence in college men: A randomized-controlled trial of GlobalConsent. BMC Public Health, v. 20, n. 1, 1 set. 2020.

1Family and Community Physician. Student of the Family and Community Medicine Residency Program of the Fortaleza Municipal Health School System, (ORCID – 0009-0008-2629-770X ) – E-mail: dinaragouveia@hotmail.com;

2Family and Community Physician. Preceptor of the Family and Community Medicine Residency Program of the Fortaleza Municipal School Health System, (ORCID – 0000-0003-0329-0341) – E-mail: otenberg21@yahoo.com.br

APPENDIX A – CHARACTERISTICS OF RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIALS ON HEALTH EDUCATION STRATEIGES AND THE INVESTIGATED OUTCOMES

Reference Sample and Population Intervention Intervention Strategy Outcome and Conclusions Alizadeh S et al. (2021) 154 pregnant women, aged between 15 and 45 years, with gestational age less than 14 weeks.

Group A (n=50)Group B (n=53)Group C (n=51)

Mean age = 28.77 yearsEducational training program called SHEP (Sexual Health Education Package), providing information such as sexual anatomy and physiology, domestic violence during pregnancy, physioloICGal changes during pregnancy, among others. Group A received the SHEP in a group setting, with three 90-minute sessions, one for each trimester of pregnancy.

Group B received self-directed training of the educational program during each trimester of pregnancy.

Group C received routine care without any sexual education materials.The sexual health education program proved to be effective in improving dimensions of sexual health during pregnancy, such as sexual activity responses, sexual quality of life, and sexual violence, especially for Group A, including sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction. Gurkan OC; Kumurcu N (2017) 136 nursing students

IG (n=63)CG (n=73)Males (n=27)Females (n=109)Mean age: 19.25 yearsTraining program for educators on combating violence against women. The program lasted for 30 hours, conducted over five different days. IG delivered information on violence against women, its effects on women’s health and well-being, strateIGes to prevent violence, and how to support women who have experienced violence. Various methods were utilized, including computer presentations, training videos, group activities, and written case studies.

CG did not participate in the program.The IG showed improvement in knowledge and attitudes regarding violence against women, as well as the ability to explain correct interventions in case studies. Peer education demonstrates effectiveness as a component in education to combat violence against women. Kostu N; Toraman AU (2021) 99 nurses and midwives

IG (n=50)CG (n=49)

Aged 29-35 years (n=12)Aged 36-46 years (n=49)Aged 41 and above (n=38)Training program based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), with sessions aimed at improving participants’ attitudes and practices regarding intimate partner violence against women and supporting the reporting of intimate partner violence against women. The sessions address gender equality, intimate partner violence against women, the effects of violence on women’s health, violence prevention, among other topics. Educational tools utilized include PowerPoint presentations, training pamphlets, film screenings, case studies, role-playing, question and answer sessions, and debates. Training based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) can be effective in improving the attitudes and practices of nurses and midwives regarding domestic violence against women and supporting the reporting of domestic violence against women. Lijster GPA et al. (2016) 815 students

IG (n=431)CG (n=384)

Males (n=415)Females (n=400)Mean age: 14.38 yearsIntervention called “Benzies & Batchies,” aimed at reducing the risk of sexual harassment behaviors among adolescents. The intervention consisted of four elements: an introductory lesson, an educational theater performance followed by a facilitated group discussion, three lessons each lasting 100-150 minutes to teach skills and resilience regarding social and sexual behavior, and a closing lesson. The Benzies & Batchies intervention was effective in reducing sexual harassment behaviors among adolescents. Miller E et al. (2015) 1,011 students aged 14 to 19 years old

IG (n=495)CG (n=516)

Males (n=240)Females (n=771)SHARP program (Sexual Health and Adolescent Risk Prevention), an evidence-based intervention aimed at preventing dating violence and sexual coercion among adolescents. The program consisted of counseling sessions, with discussions on healthy and unhealthy relationships, skills for effective communication, conflict resolution, and strategies for dealing with relationship abuse. Effectiveness demonstrated by positive changes in knowledge and attitudes regarding abuse in adolescent relationships. Miller E et al. (2020) 2,291 students

IG (n=1,040)CG (n=1,251)

Males (n=616)Females (n=1,657)Other gender (n=15)

Aged 18 to 19 years (n=935)Aged 20 to 21 years (n=931)Aged 22 to 24 years (n=392)“Providing information for trauma support and safety,” a universal intervention involving education and counseling for harm reduction. The program provides education on sexual violence, discussions on harm reduction behaviors to minimize the risk of sexual violence for oneself and peers. The intervention was conducted during visits to health centers and counseling sessions.The control group received a standard screening and brief intervention approach to assess the risk of alcohol misuse. The program did not show significant differences between the groups in the outcomes. Salazar LF, et al. (2014) 743 male high school students

IG (n=376)CG (n=367)

Mean age: 20.37 yearsIG: Web-based intervention, RealConsent, aimed at increasing intention, self-efficacy, and pro-social intervention behavior among college students to prevent sexual violence.

CG: Placebo intervention consisting of general health information unrelated to the topic of sexual violence.The RealConsent intervention took place online through a website with six modules, each lasting 30 minutes. The modules involved interactivity, educational activities, and serialized drama episodes. The RealConsent intervention benefited participants by significantly reducing perpetration of sexual violence and increasing pro-social intervention behavior compared to the control group. Scull TM, et al. (2022) 590 adolescents

IG (n=216)CG (n=374)

Males (n=239)Females (n=293)

Mean age: 14.42 yearsMedia Aware program, which is web-based. It is a media-based sexual health education approach aimed at improving adolescents’ media literacy and their communication skills regarding sexual health.

The control group did not receive any specific intervention and continued to receive standard sexual education.The Media Aware program is individualized, consisting of four lessons applied in up to four 45-minute class periods. The program covers topics such as gender role stereotypes, types of relationships, dating violence, sexual assault, transmission and prevention of STIs, as well as effective communication about sexual health. The program was effective in providing guidance on how to navigate digital media safely and responsibly. It showed a positive impact on media literacy and knowledge about sexual health, and was associated with a reduction in risky sexual behaviors among participants. Urbann K; Bienstein P; Kaul T (2020) 92 deaf and hard of hearing children

IG (n=63)CG (n=29)

Mean age: 9.66 yearsChild sexual abuse prevention program, STARK mit SAM (SmS), designed for deaf or hard of hearing children, incorporating interactive activities and group discussions. The program consists of five thematic sessions: understanding the human body, feelings, touches, secrets, and strategies for getting help. It was implemented using various creative methods and materials, with three units taught over two weeks, each lasting 180 minutes. The program is effective in improving children’s knowledge about sexual abuse prevention. Yount KM, et al. (2023) 793 heterosexual or bisexual men

IG (n=396)CG (n=397)

Mean age: 18.1 yearsIG: Received the GlobalConsent program, an online intervention aimed at preventing sexually violent behaviors and promoting pro-social behaviors.

CG: Received the AHEAD (Adolescent Health Education) online program, designed to provide general information about health and well-being.GlobalConsent took place online, consisting of six modules covering topics such as consent for sex, beliefs and norms regarding rape in relation to gender roles, effective communication, alcohol and rape, among others.

AHEAD took place online, consisting of six learning modules with durations of 35 to 45 minutes each covering topics such as brain development, nutrition, physical activity, substance use, and also sleep.The GlobalConsent program yielded positive results with a lower likelihood of men engaging in sexually violent behaviors compared to the control group.

Legend: IG = intervention group; CG = control group; STI (sexually transmitted infection).