REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.12520418

Vilson Leite Batista1

Isabela Cristina Morales1

Rodney Denevitz1

Tainara Micaele Bezerra Peixoto1

Guilherme Castello de Oliveira Lacerda2

André Lacerda de Abreu Oliveira3*

ABSTRACT

Intestinal anastomosis consists of the joining of two discontinuous segments of the gut. It is part of any procedure involving intestinal resection where the intestinal transit is preserved. Postoperative complications such as extravasation, adherence, dehiscence, perforation, peritonitis, stenosis, short bowel syndrome, shock and death are often reported related to intestinal surgeries.

Since the intestinal lumen has a high concentration of bacteria and its exposure during anastomosis increases the risk of infection, here we propose an improved aseptic anastomosis technique described in the last century. Aseptic anastomosis consists of the performance of an intestinal resection (partial enterectomy) followed by anastomosis without exposure of the lumen.

The objective of this study was to evaluate modification of the aseptic anastomosis technique with continuous and discontinuous simple suture patterns using a 4-0 polydioxanone thread, by means of clinical, histopathological and macroscopic evaluations of Wistar rats. The animals were randomly allocated to two groups (n=12). The results of the histopathological evaluations demonstrated the formation of scar tissue, degree of inflammation, collagen deposition, necrosis and neovascularization. We observed a significant difference between the groups regarding the formation of scar tissue. Between the two suture patterns, the adherence scores, inflammation degree, necrosis and neovascularization did not present significant differences. We believe that the aseptic anastomosis technique is more suitable for medium-sized and large animals.

KEYWORDS: Colonic Anastomosis, Polydioxanone, Wistar Rats.

1. INTRODUCTION

Many studies in human and veterinary medicine have sought to find more efficient intestinal suturing [6-9], since the ideal thread and technique have yet to be determined [8].

Aseptic anastomosis consists of the performance of an intestinal resection (partial enterectomy) without exposure of the lumen. Various authors have described aseptic techniques with small alterations [10-12].Therefore, the development of a practical and reproducible technique with minimum chances of contamination will reduce morbidity and even mortality among patients. The different suture patterns, both continuous and discontinuous, have not been comparatively tested in this technique, and there are very few references in the literature.

The justification for establishing an ideal technique is due to the high incidence of affections in the gastrointestinal tract that require surgical treatment, as reported for various species, including humans [1-3]. Among the main indications for intestinal surgical intervention are obstructions, traumatisms and malpositioning (such as volvulus or incarceration), besides infections and diagnostic procedures (such as biopsy, culturing, cytology and food probing) [1,2]. Complications like extravasation, adherence, dehiscence, perforation, peritonitis, stenosis, short bowel syndrome, shock and death are frequently reported after a wide range of intestinal surgeries [4,5].

Our hypothesis was that the proposed technique, with interrupted suture pattern, would reduce the cases of morbidity and mortality in colonic anastomosis, by mitigating the possibility of contamination during surgery, and also reduce the incidence of ischemia and stenosis at the anastomotic site.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

We used 12 male Wistar rats (Rattus norvegiccus) with approximate age of 8 months and average weight of 300 g. The thesis project that resulted in this article was submitted to the analysis of the Committee on Ethical Use of Animals (CEUA) of Norte Fluminense State University and was approved.

2.1 Distribution and Allocation of the Animals in Groups

After weighing each animal, we performed thee anesthetic protocol, which consisted of intraperitoneal (IP) administration of a combination of ketamine and xylazine (90 mg/kg + 9 mg/kg). For analgesia, we used tramadol hydrochloride (30 mg/kg), administered subcutaneously. The anesthetic plane was maintained with isoflurane in an open circuit with use of a mask.

The experimental surgical technique was performed by a single surgeon and a single helper, both with experience in surgery of the gastrointestinal tract.

The animals were divided into two groups of six each, both subjected to aseptic anastomosis of the colon, with continuous or interrupted suture pattern:

Group 1 (G1) – colonic anastomosis with interrupted simple suture pattern.

Group 2 (G2) – colonic anastomosis with continuous simple suture pattern.

Below we describe all the surgical steps of the experiment. Item “i” corresponds to the time difference between the groups.

a) Pre-retro umbilical midline laparotomy with extension of 4 cm; b) exposure of the distal colon; c) divergent malaxation in cases when the gut segment to be incised contained fecal material; d) isolation of the segment with sterile gauze compresses; e) circumferential seromyotomy, proximate and distal to the portion to be resectioned; f) application of intestinal hemostatic forceps, proximate and distal to the seromyotomy site; g) formation of a mucus cuff on the ventral face of both pinched sections, by applying a U-shaped mattress suture with 5-0 polydioxanone thread (PDS) (Ethicon©); h) resection of the isolated intestinal segment and removal of the hemostatic forceps, with the colon remaining closed due to the mucus cuff; i) approximation and anastomosis via extramucosal sutures (continuous or discontinuous) from the mesenteric border to the antimesenteric border with 5-0 polydioxanone thread (PDS) (Ethicon©); j) removal of the mucus cuff, restoring the intestinal patency; k) repositioning of the intestinal loop, respecting the organic syntopy and holotopy, peritoneum synthesis and muscular layer in a single plane, with U-shaped mattress suture using 4-0 mononylon thread (Ethicon©); and l) intradermal suture with 5-0 mononylon thread (Ethicon©).

2.2 Macroscopic Evaluation and Euthanasia

In the clinical study, the animals were evaluated once a day for 10 days by the same blinded observer and assigned scores based on the M-CASS table, which classifies the severity of clinical signs directly by the sum of scores. Parameters such as coat appearance, eyelid appearance respiratory movements and sounds, and general activity and behavior were recorded.

At the end of the study, the animals were euthanized with 180 mg/kg of intraperitoneal sodium thiopental. The abdominal cavity was exposed by the exploratory laparotomy method and the intestinal loops were examined. We searched for signs of colon impaction proximal and distal to the anastomosis site, adherence of intestinal loops and free liquid in the cavity. In the post-mortem assessment, the analytes were categorized as present or absent.

2.3 Histopathological Study

The animals were necropsied after death and fragments from the surgical site and distal region of the descending colon were collected for preparation of slides, and evaluated for the formation of scar tissue, inflammation and necrosis.

The formation of scar tissue, inflammation degree, collagen deposition, necrosis and neovascularization were analyzed by the scanning method. The indicators were identified as slight (+), moderate (++), severe (+++) or not observed (NO).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The results are presented by means of two graphs: a bar graph and a scatter dot plot. The bar graph displays the comparison between the groups (G1xG2). The x-axis denotes the degree of differentiation of the analyte and the y-axis indicates the number of animals of the group. To construct the bar graph, we used the Fisher (Chi-squared) test to calculate the level of significance.

The scatter dot plotrepresents the distribution and variance of the parameters presented in the same group. For this purpose, we used the Wilcoxon test to calculate the level of significance. To estimate the survival function, we used the Kaplan-Meier curve, and the Mantel-Cox test to calculate the level of significance. Results were considered statistically significant when p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

The results are didactically divided into microscopic and macroscopic evaluation.

3.1 Histopathological Evaluation

N=6 per group.

Source: research data (2021).

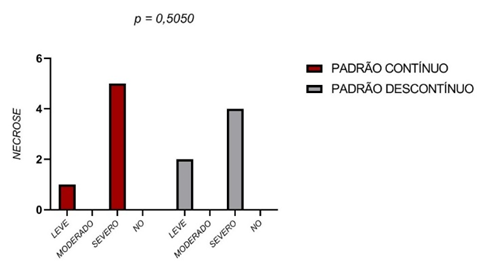

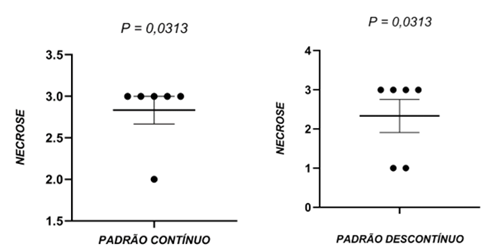

3.1.2 Tissue necrosis

With respect to tissue necrosis, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups. The severe necrosis score was assigned to the majority of the samples analyzed (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Tissue necrosis

In the individual analysis, the animals of group G2 and group G1 showed statistically significant differences regarding tissue necrosis. Again, the severe necrosis score was assigned to the majority of the samples (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Tissue necrosis process of groups G1 and G2

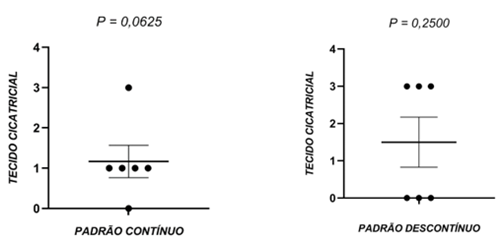

3.1.3 Scar tissue

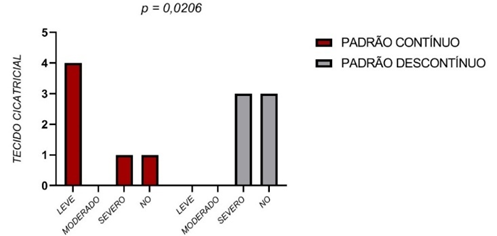

A statistical difference was observed between the groups regarding the formation of scar tissue (Figure 5). In the animals receiving the continuous sutures, the slight score was most frequent, while the severe score was most often assigned to animals receiving discontinuous sutures.

Figure 5 – Scarring

The scores denoting the formation of scar tissue were classified as slight, moderate, severe or not observed (NO). Comparison of the results by the Fisher (Chi-squared) test did not reveal a statistically significant difference (P>0.05).

There also were no significant differences when comparing the results of the animals within each group(Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Scarring within the groups G1 and G2

As before, the scores denoting the formation of scar tissue were classified as slight, moderate, severe or not observed (NO). Comparison of the results by the Wilcoxon test did not demonstrate significant pairwise differences between the animals in the same groups (P>0.05), N=6 per group.

3.2 Macroscopic Evaluation

Besides the analysis of survival during the 10 days of the study, the animals were evaluated by the clinical staging method regarding the coat appearance, feces appearance, activity, behavior, respiratory movements, respiratory sounds and eyelid appearance, according to the M-CASS table. After euthanasia, the animals were evaluated regarding the presence or absence of intestinal impaction, adherence of intestinal loops and free liquid in the abdominal cavity.

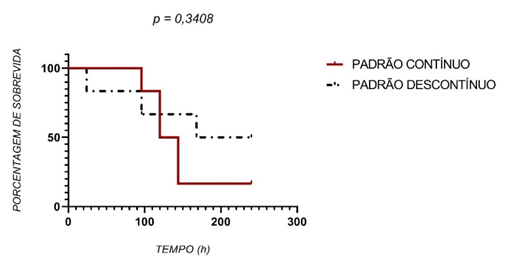

3.2.1 Survival analysis

The survival of the group receiving continuous sutures was lower than of the group receiving discontinuous sutures, but the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (Figure 7).

Figure 7 – Kaplan-Meier curve showing the survival in hours after aseptic anastomosis in the murine intestine

The analysis by the Mantel-Cox test also showed no significant difference between the groups (P>0.05).

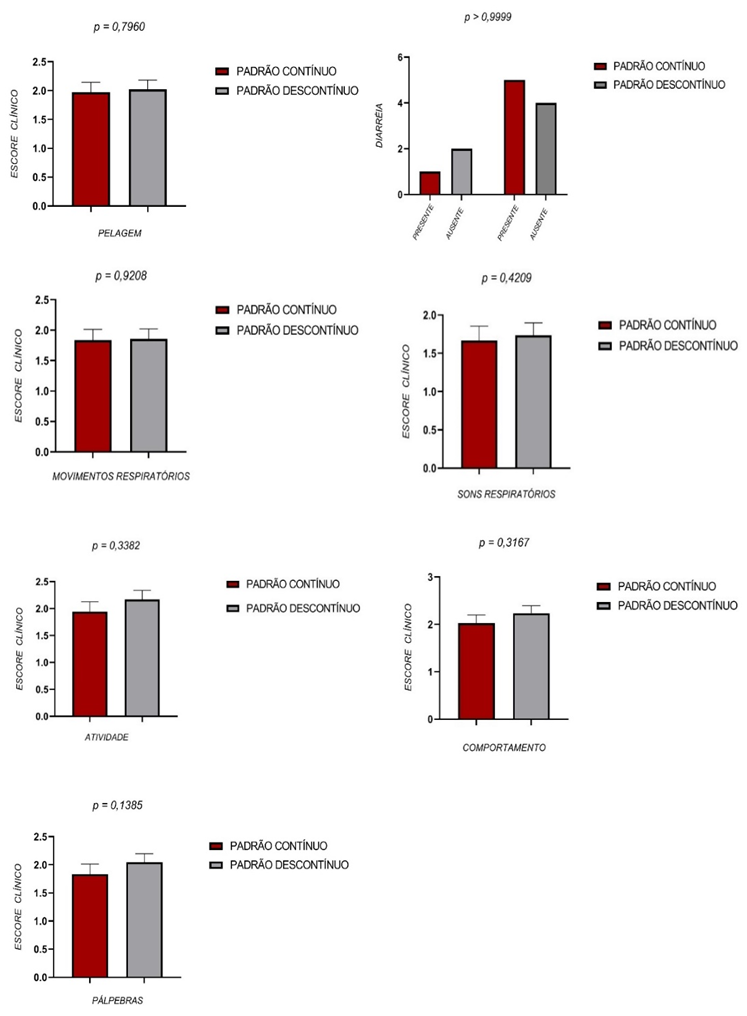

3.2.2 Clinical scoring

The clinical scores were evaluated and recorded once per day by a blinded observer. Both groups presented very similar patterns, without statistical differences (Figure 8).

Figure 8 – Clinical scoring

Figure 8 depicts the clinical parameters obtained daily in the animals submitted to aseptic anastomosis of the intestine. The criterion diarrhea was evaluated by the Fisher test. The comparison between the values on each day by the Mann-Whitney and Fisher tests (diarrhea) between the two groups did not show a significant difference (P>0.05).

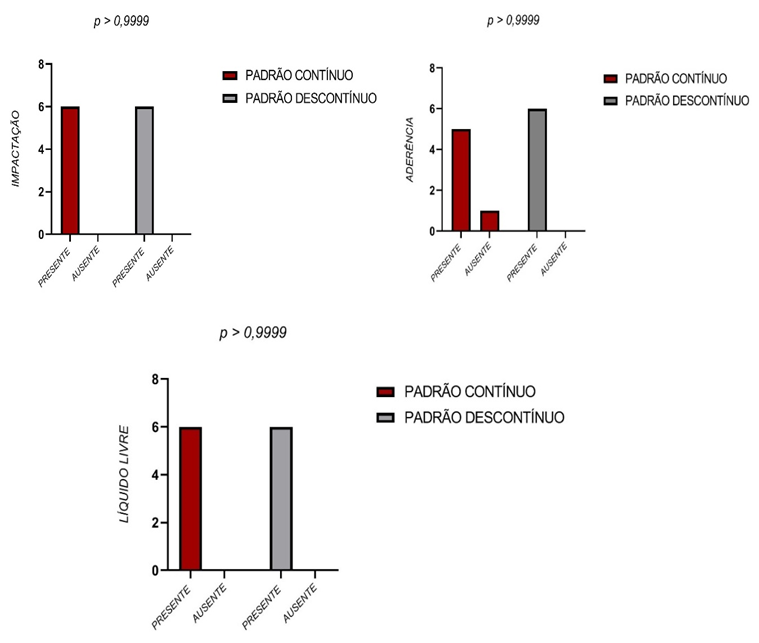

3.2.3 Impaction, adherence and free liquid

There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding the intestinal impaction, intestinal loop adherence and free liquid in the abdominal cavity.

Figure 9 – Impaction, adherence and free liquid

Figure 9 depicts the anatomopathological parameters intestinal impaction, intestinal loop adherence and free liquid in the abdominal cavity observed in the post-mortem examination of the animals submitted to aseptic anastomosis of the intestine. According to the Fisher test, there were no significant differences between the two groups (P>0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

The original aseptic technique was developed with dogs having minimum weight of 15 kilograms, with the objective of surgically exposing the intestinal lumen. We used Wistar rats, which obviously have much smaller intestinal size. Our novel technique in this study used “Greek bar” sutures formed by absorbable monofilament thread of polydioxanone (5-0) to maintain the intestinal lumen occluded. The original technique uses cotton multifilament thread (0). We believe that the absorbable monofilament thread generates less severe infectious and inflammatory complications than the cotton multifilament thread used in the original technique.

The results of this study did not reveal statistically significant differences between the suturing techniques analyzed. With regard to survival, there was no significant difference, although the animals receiving discontinuous sutures had longer survival time. The majority of the deaths were caused by intestinal impaction. This finding can be explained by the diameter of the intestinal lumen of rats, in which the continuous suture caused a higher degree of obstruction.

In rats, the time for intestinal scarring to occur is not well defined. Nevertheless, our results demonstrated that in 10 days, the group receiving discontinuous sutures had a score of 3 (severe) regarding the presence of scar tissue in the sample analyzed, while for the group receiving the continuous sutures, the most common score was 1 (slight).

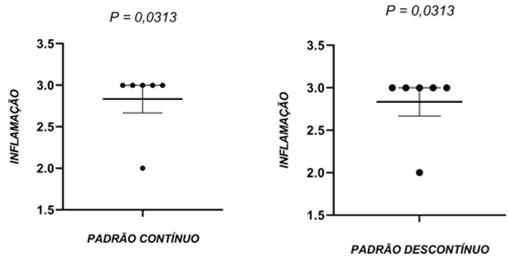

In the case of the inflammation scores, both groups (continuous and discontinuous sutures) had score considered severe and there was no statistical difference in this evaluation. When evaluating the animals within each group, there was a significant difference in the group receiving continuous sutures, with indication of severe tissue inflammation.

Besides these aspects, we evaluated the presence of tissue necrosis in the samples collected, finding no significant differences between the two groups. The severe necrosis score was most common in the samples studied. Individual analysis showed that the animals of both groups showed significant pairwise differences regarding tissue necrosis. The severe score occurred the most in the samples analyzed. Although using different techniques, the results found by other researchers [14] were similar to those found in our study, in which the animals presented severe necrosis as the suture site, and some showed bacterial proliferation of surrounding areas, demonstrating that necrosis is the final manifestation of cells subject to irreversible lesions, characterizing cell death, as also reported by [15].

During the 10 days of the experiment, the animals were submitted to the clinical staging method for evaluation of the coat appearance, feces appearance, activity, behavior, respiratory movements, respiratory sounds, and eyelid appearance, according to the M-CASS table. We did not find any significant differences between the clinical scores of the two suture groups. After euthanasia, the animals were evaluated regarding the presence or absence of intestinal impaction, adherence of intestinal loops and free liquid in the abdominal cavity. The qualitative analysis of these three parameters did not reveal any significant differences between the two experimental groups.

Adherence of intestinal loops was found in animals of both groups. We believe that together with the severe inflammation scores found, the adherence of loops was caused by the dispersion and deposition of fibrin and collagen on the surface of the affected tissues due to the high concentration of inflammatory mediators.

In the macroscopic evaluation, all the animals presented intestinal impaction. This result can probably be attributed to the small diameter of the colon of rats (especially in comparison with dogs). Hence, the aseptic technique is likely better suited for medium-sized and large animals.

We did not evaluate the peritoneal fluid, preventing any inferences about the cause of that reaction. This evaluation is recommended in future studies.

5. CONCLUSION

The intestinal loop diameter should be considered when choosing a surgical technique, since the majority of the rats in this study suffered from postoperative intestinal impaction. Medium-sized and large animals can benefit the most from the aseptic anastomosis technique.

Regarding the tissue reactions studied by histopathology, only the deposition of scar tissue in the continuous technique had a statistically significant difference, but this did not alter the outcome of the anastomosis.

The technique described here has possible clinical applications, but due to the small number of published articles (despite the relevance of the subject) and the large-scale practice of anastomosis performed with the current sutures and patterns, further studies are necessary in this respect.

REFERENCES

1 FOSSUM, T. W.; HEDLUND, C. S. J. V. C. S. A. P. Gastric and intestinal surgery.v. 33, n. 5, p. 1117-1145, 2003. ISSN 0195-5616.

2HUNT, J. M.; EDWARDS, G.; CLARKE, K. W. J. E. V. J. Incidence, diagnosis and treatment of postoperative complications in colic cases.v. 18, n. 4, p. 264-270, 1986. ISSN 0425-1644.

3 LUIJENDIJK, R. et al. Foreign material in postoperative adhesions.v. 223, n. 3, p. 242, 1996.

4 FINCK, C. et al. Radiographic diagnosis of mechanical obstruction in dogs based on relative small intestinal external diameters. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound, v. 55, n. 5, p. 472–479, 2014.

5 FERNANDEZ, Y. et al. Ileocolic junction resection in dogs and cats: 18 cases. The Veterinary quarterly, v. 37, n. 1, p. 175–181, 2017.

6 FERNANDES, L. C. et al. Estudo comparativo entre anastomosiss intestinais com sutura manual e com anel biofragmentável em cães sob a administração de corticosteróides. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, v. 46, n. 2, p. 113–120, 2000.

7 DEMYTTENAERE, S. V. et al. Barbed suture for gastrointestinal closure: A randomized control trial. Surgical Innovation, v. 16, n. 3, p. 237–242, 2009.

8 BERNIS-FILHO, W. O. et al. Estudo Comparativo Entre Os Fios De Algodão, Poligalactina e Poliglecaprone Nas Anastomosiss Intestinais De Cães. Arquivo Brasileiro de Cirurgia Digestiva, v. 26, n. 1, p. 18–26, 2013.

9 GYS, B. et al. Laparoscopic Linear Stapled Running Enterotomy Closure in Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Using Absorbable Unidirectional Barbed Suture (Stratafix® 2/0). Obesity Surgery, v. 27, n. 10, p. 2740–2741, 2017.

10 MORTENSEN, N. J.; ASHRAF, S. Intestinal anastomosis 2008.

11 PARKER, E. M.; KERR, H. H. J. B. J. H. H. Intestinal anastomosis without open incisions by means of basting stitches.v. 19, n. May, p. 132, 1908.

12 WEBSTER, J. P. J. A. O. S. Aseptic end-to-end intestinal anastomosis.v. 81, n. 3, p. 646, 1925.

13 SANTOS, C. H. M. et al. Differences between polydioxanone and poliglactin in intestinal anastomosiss – a comparative study of intestinal anastomosiss. Journal of Coloproctology. 2017, 37. 04. 263-267.

14 MCCARTHY, C.K., MCGAHA, P.K., ROZICH, N.S., YOKELL, N.A., LEES, J.S., BERRY, W.L. Creation of Colonic Anastomosis in Mice. Journal of Visualized Experiments, (143), e58742, 2019.

15 TORRES NETO, J. R. et al. Estudo Histomorfométrico de Anastomosiss Primárias de Cólon em Coelhos, Com e Sem Preparo Intestinal. Revista Brasileira de Colo-proctologia, 2007;27(4): 384-390.

16 BROCHHAUSEN, C. et al. Review Intraperitoneal adhesions — An ongoing challenge between biomedical engineering and the life sciences. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, v. 98A, n. 1, p. 143–156, 2011.

17 YAMAGUCHI, R. et al. Effects of Platelet-Rich Plasma on Intestinal Anastomotic Healing in Rats: PRP Concentration is a Key Factor. Journal of Surgical Research, v. 173, n. 2, p. 258–266, 2012.

1 – Doutorando (a) em Ciência Animal na Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF)

2- Estudante de Graduação em medicina veterinária da Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF).

3- Professor de Cirurgia na Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro (UENF).

* Autor de Correspondência: Av. Alberto Lamego, 2000, Unidade de Experimentação Animal – Parque California, Campos dos Goytacazes/RJ , CEP: 28013-602, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense (UENF) – Campos dos Goytacazes/RJ – Brazil. Email: andrevet@uenf.br