REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/ni10202506191232

Fernando Sérgio Oliveira1

Gislaine Alves Oliveira2

Bruno Dutra Arbo3

Maria Flávia Marques Ribeiro4

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to develop and evaluate an asynchronous online Human Physiology course delivered via the Moodle platform, without direct instructor presence, targeting undergraduate and graduate students. The course content was structured into six chapters and incorporated diverse didactic resources, including explanatory texts, videos, comic strips, and self-assessment tests. Students had full autonomy to select both the topics and the order of study, with a final exam required for course completion. Across three offerings, 157 students enrolled, 83 completed the final exam, and 39 achieved a passing score (46.9%). The most frequently reported advantages of the online format over traditional instruction included greater satisfaction, motivation, the possibility of content review, and flexible access. Platform data revealed that the assessment tools accounted for 10,642 views, significantly surpassing engagement with other materials (1,728 views). Although students self-reported improvements in understanding, memorization, perceived learning, motivation, and overall satisfaction, these perceptions were not reflected in enhanced performance on objective assessments. The findings suggest that, while digital resources and student motivation contribute positively to the learning experience, they may not be sufficient to significantly improve learning outcomes in isolation. Therefore, additional pedagogical strategies—such as promoting peer interaction, instructor engagement, and structured study guidance—may be necessary to foster meaningful learning and academic performance in online physiology education.

Keywords: Online learning, motivation, satisfaction, physiology education, autonomous learning.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

This study shows that an asynchronous online Physiology course increased students’ motivation, satisfaction, and perceived learning, but did not improve performance in objective tests. Although the flexibility and autonomy were positively evaluated, high engagement with assessments did not translate into better outcomes. The findings highlight that motivation and access to digital content alone are insufficient, and that additional strategies—such as promoting interaction and providing study guidance—are essential to enhance learning in online environments.

Keywords: online learning, student motivation, physiology education

INTRODUCTION

The incorporation of digital technologies into education has expanded the possibilities for teaching complex subjects such as Human Physiology. However, this transformation also presents significant challenges. Human Physiology encompasses a broad and interconnected set of concepts, requiring students to develop advanced skills in integration and critical reasoning. Additionally, its specialized terminology—often unfamiliar in everyday contexts—can further hinder comprehension and engagement. These factors contribute to the frequent perception of physiology as a difficult subject, which may lead to reduced student motivation and low academic performance.

Despite these challenges, the digital environment offers numerous opportunities to enhance the learning process. Online courses, in particular, have gained relevance as flexible and scalable tools for delivering content. By integrating a variety of resources—including texts, videos, podcasts, comic strips, and self-assessment tools—online platforms can foster a more dynamic and personalized learning experience. These multimodal strategies can stimulate student attention and facilitate content retention. Moreover, asynchronous delivery allows students to learn at their own pace, review material as needed, and manage their time according to individual routines.

The flexibility and interactivity offered by online learning environments are particularly valuable in the context of health and life sciences education, where traditional lectures often fail to address individual learning differences. Several studies have demonstrated that the integration of visual, auditory, and textual resources can enhance student engagement and promote deeper understanding of physiological processes. Furthermore, the short duration of many online courses and their ease of access may contribute to broader participation and reduced dropout rates, especially among students balancing academic, professional, and personal responsibilities.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that increased satisfaction and motivation do not necessarily result in improved learning outcomes. The effectiveness of online courses depends not only on the quality and diversity of instructional materials but also on students’ ability to engage actively with the content. Developing self-regulation, time management, and study autonomy is essential for success in asynchronous learning environments. Therefore, beyond content delivery, the design of online courses should consider strategies to support these metacognitive skills.

Although several studies have explored the role of digital tools in improving engagement and satisfaction in health education, there remains a lack of robust evidence on their direct impact on learning outcomes—especially in contexts where no direct interaction with instructors is provided. The literature also shows limited investigation into how student autonomy is actually developed and exercised in fully asynchronous physiology courses. Most existing research tends to evaluate hybrid or instructor-supported models, leaving a gap in understanding the effectiveness of fully independent, self-guided digital learning formats in this discipline.

Given this gap, there is a pressing need to investigate whether the motivational and satisfaction gains observed in asynchronous digital learning environments are sufficient to enhance academic performance in content-heavy, conceptually demanding disciplines like Human Physiology. In this context, the present study aimed to design, implement, and assess a self-paced online physiology course—delivered via Moodle without instructor supervision—focusing on its effects on students’ autonomy, motivation, satisfaction, and learning outcomes. The findings may contribute to advancing pedagogical strategies in online science education and inform future course design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Course Development and Delivery

An asynchronous online course on Human Physiology was developed at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Brazil, with the objective of offering innovative didactic strategies not commonly used in traditional instruction, including educational videos and comic strips. The course was delivered via the Moodle platform due to its flexibility, user-friendliness, and wide accessibility. It was offered on three separate occasions to undergraduate and graduate students, identified in this study as Course 1 (June 2021), Course 2 (September 2021), and Course 3 (December 2021).

Instructional Design and Didactic Material

A multidisciplinary team—composed of one faculty member and six students (one Ph.D. candidate, one Master’s student, and four undergraduate students from health-related programs —was responsible for developing the educational content. The material was structured into six chapters: The Cell and Levels of Organization, Compartments and Homeostasis, Water and Solubility, Energy and Metabolism, Membranes and Transport, and Protein Synthesis.

Each chapter incorporated diverse pedagogical resources, including summary texts, short videos (under 10 minutes), original illustrations, comic strips, and interactive multiple-choice quizzes. Illustrations were either produced by the team using Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop or adapted from public-domain sources. Videos were created and edited using Canva, with narration provided by a team member to enhance understanding of the written content. Comic strips were developed to present fictional narratives that contextualized physiological concepts in an engaging and accessible format. At the end of each chapter, 10 multiple-choice review questions were included to reinforce learning. Additional open-ended prompts encouraged students to explore content independently, highlighting key concepts and curiosities related to the subject matter.

Course Promotion and Accessibility

The course was advertised through institutional social media channels and email lists, and was open to students from various higher education institutions. Registration was conducted via Google Forms, and participants received individual logins to access the Moodle platform. All course materials were available 24/7 throughout the duration of the course, providing full autonomy to students in terms of pacing and content navigation.

Academic and Technical Support

Student support was available throughout the course via asynchronous discussion forums and email communication. The supervising professor moderated the discussion forums, fostering academic dialogue, while a designated team member responded to student inquiries submitted by email. This support structure aimed to provide clarification and guidance while preserving the self-directed nature of the course.

Evaluation of Student Performance

To assess learning outcomes, participants completed a pre-test prior to accessing the course materials and a final test upon course completion. Both tests consisted of 10 multiple-choice questions designed to evaluate fundamental knowledge in Human Physiology. The questions were tailored to a beginner level and reviewed for content validity. A minimum score of 7 out of 10 on the final test was required for course completion.

Perception and Satisfaction Questionnaire

Participants who consented to take part in the study also completed a post-course evaluation questionnaire, which included both objective and open-ended items. A Likert scale was used to assess satisfaction, motivation, perceived learning, and usability of course components. Multiple-choice questions allowed for selection of more than one response, providing a nuanced understanding of student perceptions.

Statistical Analysis

The sample was selected by convenience, including only those students who agreed to participate in the research component. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Data from pre- and post-tests were analyzed using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test. One-way ANOVA was used to compare mean scores across the three course offerings. Paired t-tests were applied to evaluate differences between pre- and final test scores within each cohort and across all courses combined. Descriptive statistics, including absolute and relative frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were used to summarize questionnaire responses.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (Protocol No. 25586419.6.0000.5347). Participation in the research component was voluntary and independent from participation in the course. Upon registration, students were informed of the study objectives and invited to participate. Those who agreed signed an informed consent form electronically before completing the pre-test. Only data from participants who provided formal consent were included in the analyses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

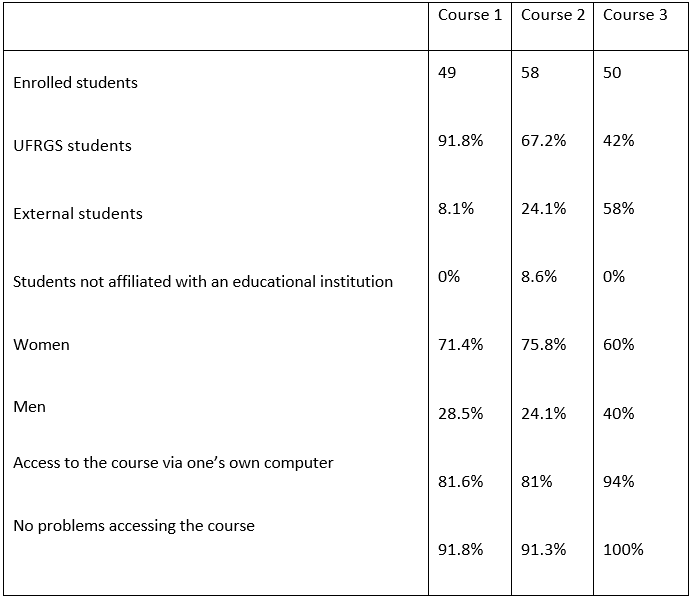

There were 157 students enrolled in the course. Of these, 142 took the pre-test, 83 took the final test, and 50 evaluated the course (course 1 – n=10, course 2 – n=25, and course 3 – n=15). The students were from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and other higher education institutions in Brazil. Of the students external to UFRGS (n=47), 51% were from the Federal University of Pampa, located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and five students reported not being linked to any educational institution. More than 80% accessed the course through their own computers, and over 90% reported no access issues (Table 1). Internet access, often a barrier to online learning, was not a significant challenge for these students. Current widespread internet availability supports its powerful role in education, as noted by Terra (22), with Bacich and Moran (1) emphasizing the importance of internet integration from elementary to university education.

Only 83 of the 157 enrolled students (52.8%) completed the final test. Possible explanations include course dropout, students reviewing material without interest in certification, demotivation, lack of time, disappointment, or low confidence in passing the exam. Dropout rates in online courses vary widely—from 26.3% to 85%—as reported by Oliveira, Oesterreich, and Almeida (19). Factors such as reduced teacher contact, time constraints, and difficulties navigating new technologies and virtual learning environments contribute to this attrition (21).

The course forum provided a platform for dynamic student interaction and content discussion, yet participation was minimal. In course 1, 14 students accessed the forum but posted no messages. For courses 2 and 3, the team adjusted their approach by actively “provoking” discussions, resulting in 30 students visiting the forum, though only four posted messages. Vieira (24) highlights the necessity of well-structured forums and teacher encouragement to stimulate student involvement. Low forum engagement may stem from lack of interest, shyness, insecurity, limited time, or students waiting for others to initiate discussion. The increased activity after modifying the forum strategy suggests that active facilitation by course organizers is critical to maximizing forum effectiveness.

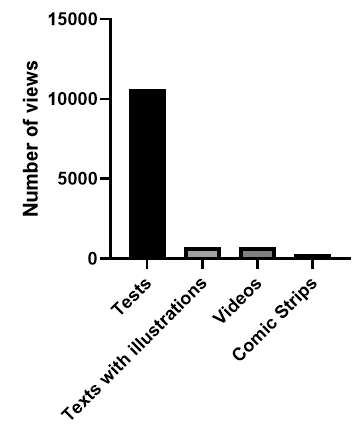

In addition to engagement challenges, the preference for assessment tests over other interactive tools, such as videos and comic strips, indicates students tend to favor familiar evaluation methods. This reliance on traditional testing may limit the impact of innovative educational resources designed to enhance comprehension and motivation. As Moran (17) suggests, pedagogical methods should be reconsidered to encourage students to explore diverse learning tools beyond conventional assessments.

Furthermore, the high initial pre-test scores may have caused a ceiling effect, limiting measurable improvement in final test results. This suggests students entered the course with foundational knowledge, reducing observable learning gains. Future course designs could implement differentiated assessments to accommodate varying proficiency levels, thereby fostering challenge and engagement for all participants.

Advantages of the online course compared to the traditional teaching model

The positive perception of online learning modalities by students, particularly regarding flexibility and access to materials, highlights a crucial advantage in contemporary education. As institutions increasingly adopt hybrid or fully online formats, these benefits address common barriers in traditional teaching, such as fixed schedules and limited review opportunities. However, the disparity in satisfaction among graduate students suggests that online content must be carefully tailored to different academic levels to maintain engagement and relevance. This finding underscores the need for adaptive instructional design that considers prior knowledge and learning goals, particularly in advanced or review courses.

Despite high satisfaction and motivation, the lack of significant improvement in final test scores indicates that positive perceptions alone do not guarantee enhanced learning outcomes. This gap suggests that factors beyond material accessibility, such as study habits, self-regulation, and interaction with content, critically influence knowledge acquisition in online settings. Previous studies have noted that student autonomy is a double-edged sword; while it can empower learners, it may also lead to challenges for those less experienced in self-directed learning. Therefore, online courses should integrate scaffolding strategies and continuous feedback mechanisms to better support diverse learner profiles and promote deeper comprehension.

Furthermore, the minimal engagement observed in interactive components such as discussion forums calls attention to the importance of active facilitation and community building in virtual environments. Engagement strategies, including timely instructor interventions and peer-to-peer interactions, are essential to create a supportive learning community that fosters motivation and critical thinking. Future course iterations could benefit from incorporating synchronous sessions, gamification elements, or collaborative projects to increase student interaction and investment. Such approaches have been shown to mitigate feelings of isolation and promote a richer educational experience in distance learning.

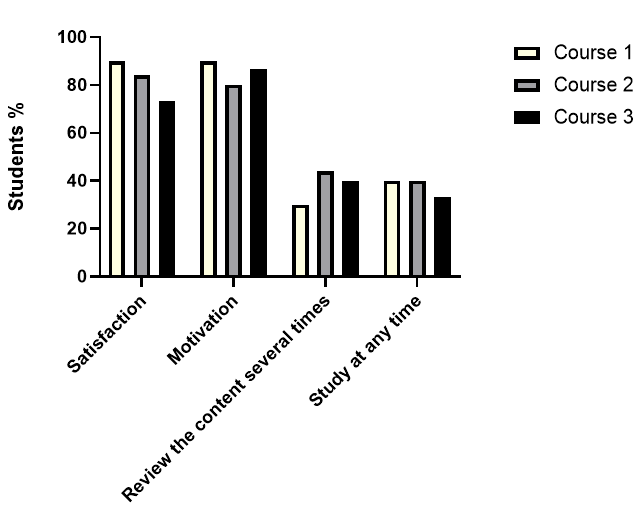

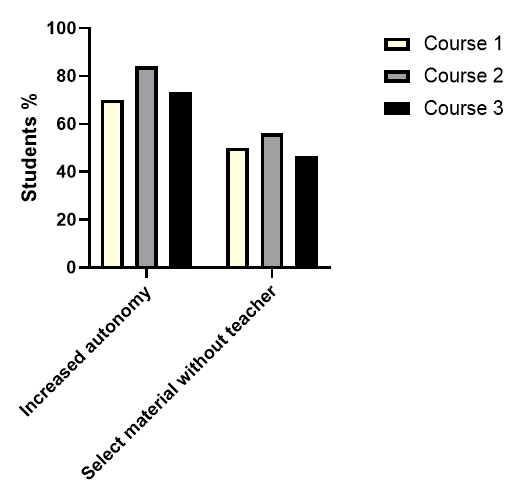

Students reported that there are advantages of the online course compared to the traditional teaching model, including satisfaction, motivation and the possibility of reviewing and studying the content at any time (Figure 01). These results align with Terra (22) and Moran (17), who argue that the use of platforms and technological tools in virtual learning environments can be used in a simple, detailed and dynamic way in order to attract the student’s attention.

Another important point shown in the survey is the satisfaction and motivation of students with this teaching modality. Students were asked “What is your degree of satisfaction with the use of the material (did you like the material or not)?”. The high percentage of satisfaction of students who took the courses (more than 73%) is in accordance with the study performed by Diniz (12), which was carried out with 152 students in distance education courses in administration, accounting sciences and information systems from a Brazilian university. He concluded in his study that more than 70% of students are satisfied with this type of education. Benevides (4) also states that students, for the most part, feel satisfaction in attending this type of course.

It was observed that the lowest percentage of satisfaction (73.3%) was in the course composed exclusively of graduate students. These findings were not surprising, given that the course 3 students were reviewing basic concepts of Human Physiology, while most of the students from courses 1 and 2 were having contact with these contents for the first time. Even so, the degree of satisfaction was high (Figure 01).

Student performance on the final test

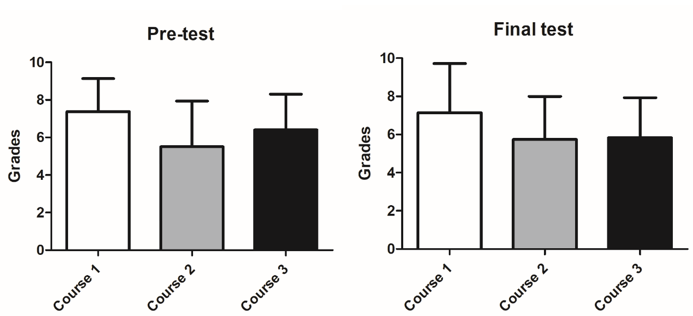

Despite the high levels of satisfaction and motivation reported by students, no statistically significant improvement was observed between pre-test and final test scores across all courses (Figure 03). These findings contradict our initial hypothesis that participation in the course would enhance student performance on the final assessment. Although students perceived an increase in their learning, this perception was not reflected in measurable gains.

Several factors may explain the absence of score improvement. The course material might not have been fully accessible or comprehensible to all students, potentially limiting their engagement and effective use of available resources. Additionally, the students’ level of autonomy could have been insufficient to capitalize on the course tools. The assessments themselves may have lacked adequate validation, possibly failing to accurately measure learning progress. It is also plausible that some students devoted minimal effort to studying, opting for only superficial review. Furthermore, the relatively high pre-test scores suggest a ceiling effect, reducing the potential for measurable improvement. Lastly, since the course was offered as a non-credit extension program rather than for academic credit, student motivation and time commitment may have been lower compared to credit-bearing courses.

Moreover, the online learning environment demands higher self-regulation and time management skills, which may not have been adequately developed by all participants. Without structured deadlines or continuous instructor oversight, some students might have struggled to maintain consistent study habits, negatively impacting performance outcomes. This highlights the need for integrating supportive mechanisms that foster self-directed learning competencies within online course designs. Implementing scaffolding strategies, such as periodic check-ins and guided activities, could mitigate these challenges and promote deeper engagement.

It is also important to consider the potential impact of the course’s pedagogical approach. The reliance on traditional assessment formats, such as multiple-choice tests, might not fully capture the depth of student understanding or the development of higher-order cognitive skills. Diversifying evaluation methods to include formative assessments, project-based tasks, or reflective activities could provide a more comprehensive picture of student learning and better align with the dynamic nature of online education. This could also enhance motivation by offering varied opportunities to demonstrate knowledge beyond rote memorization.

Furthermore, external factors such as students’ personal circumstances, workload, and competing responsibilities may have influenced their engagement and performance. Given that many participants accessed the course independently and outside formal academic programs, varying degrees of commitment and external stressors are likely to have affected study intensity and exam preparation. This phenomenon is consistent with challenges reported widely in distance education, where balancing academic work with professional and personal life requires significant effort and resilience.

Finally, the course’s duration and intensity might have limited students’ ability to assimilate and apply new knowledge effectively. Short-term extension courses often face constraints in depth and breadth of content coverage, which can affect learning outcomes. Future iterations could consider extending course length, increasing interactive components, and providing personalized feedback to support progressive mastery of the material.

Student autonomy

Although most students consider online courses advantageous, this type of pedagogical strategy also causes difficulties for those who are not accustomed to studying independently (17). The survey showed that less than 56% of students from courses 1, 2, and 3, including both graduate and undergraduate students, reported the ability to select material without the help of the teacher (Figure 04). Regarding autonomy (Figure 04), the results were notable, with more than 70% of students from all courses claiming that the course increased their autonomy.

These results align with observations by Veras et al. (23), who state that students in distance learning courses often face severe difficulties in organizing their studies without teacher presence, and that developing autonomy is a challenging and lengthy process requiring student commitment and institutional support. Basegio (2) highlights that this autonomy is partial, as students possess only some of the skills indicative of full autonomy in the learning process.

This teaching modality demands skills and attributes from students that traditional teaching does not require as strongly. Without the constant presence of a teacher, students are responsible for organizing their study time, selecting the most important content, utilizing various tools, and seeking answers to questions that arise during study. Parechi (20) asserts that autonomy in online courses depends on the students’ ability to interact and receive mediation during the learning process. Autonomy is dynamic and constructive; the student shifts from a passive to an active role by taking responsibility for their training through interaction with others, critical thinking, exchange of experiences, and mastery of new technologies offered by the institution (1).

Moreover, variability in students’ digital literacy significantly impacts their capacity to benefit from online learning environments. Students with higher digital skills navigate platforms more efficiently, engage with interactive tools, and troubleshoot technical issues independently. Conversely, those with limited digital proficiency may experience frustration and disengagement, which negatively affects autonomy and learning outcomes. Therefore, integrating digital literacy training into the curriculum is essential to equalize opportunities and enhance student autonomy.

In addition, motivation plays a crucial role in fostering autonomous learning in virtual settings. Intrinsic motivation drives students to engage deeply with material, seek additional resources, and persist despite challenges. Online courses that incorporate elements fostering intrinsic motivation—such as content relevance, opportunities for choice, and recognition of progress—tend to promote higher levels of autonomous engagement. Understanding and addressing motivational factors is critical in designing effective online learning experiences that cultivate autonomy.

Furthermore, the social dimension is essential to autonomy development. Although autonomy emphasizes independent learning, collaborative interactions remain vital. Peer discussions, group projects, and social presence within the learning environment provide emotional support and opportunities for knowledge exchange that enrich the learning process. Such social engagement can reinforce student confidence and encourage ownership of the learning journey, contributing to more effective autonomy in online education.

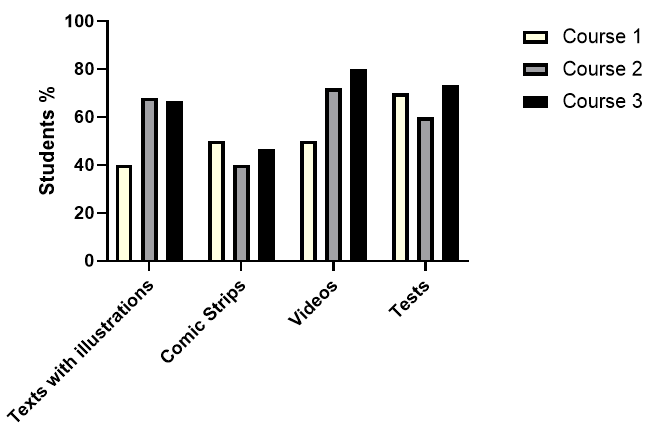

Student perception of tools that enhance learning

The course was structurally designed to offer multiple integrated tools aimed at capturing student attention, enhancing motivation and satisfaction, and ultimately improving learning outcomes. Although no consistent pattern emerged across the three courses regarding tool preference, comic strips were the least favored resource among students in courses 2 and 3 (Figure 05). This may reflect a perception that comic strips, as an unconventional format, contribute less directly to learning. It is noteworthy that course 1 deviated from this pattern, possibly due to its smaller evaluation sample size (n = 10).

Among the alternative tools provided—videos, illustrated texts, comic strips, and tests—students showed a clear preference for tests (Figure 06), which received 10,642 views compared to 719 views each for texts and videos. The stark difference in engagement suggests a strong student habituation to traditional assessment formats as the primary means of knowledge verification.

Assessment tests have been shown to aid content retention and foster student confidence regarding their knowledge level (5). Our findings corroborate this, revealing a marked student preference for tests over other materials. This is consistent with prior research, such as Brossi (6), who found that 73% of high school students favored evaluation via tests, and Lopes et al. (16), whose study indicated university students prefer non-consultation testing. Borges et al. (5) similarly emphasize that frequent testing not only satisfies student preferences but also supports learning.

However, despite tests being the most utilized tool, they did not translate into improved performance on the final exam. This raises questions about whether reliance on test-based study is the most effective learning strategy. A prevailing student culture equates tests with memorization, which may limit deeper understanding. Moran (17) argues for a pedagogical shift toward teaching methods that enable students to explore diverse tools and discover novel ways to enhance learning.

Our initial hypothesis anticipated a preference for more “modern” tools, such as videos, illustrated texts, or comic strips, which were expected to facilitate better learning and performance. Yet, student behavior and final test outcomes did not support this. Bacich and Moran (1) highlight that the mere presence of varied and engaging tools is insufficient if students lack the autonomy and intrinsic motivation to actively engage with them. This underscores the need to foster learner autonomy alongside diversifying instructional materials.

Moreover, the findings suggest that students may benefit from structured guidance on how to effectively use diverse learning resources, as mere availability does not guarantee meaningful engagement. Incorporating instructional scaffolding could enhance students’ ability to navigate and integrate different media, thus improving learning outcomes. Additionally, active pedagogical interventions, such as frequent feedback and formative assessments, may encourage deeper cognitive processing beyond rote memorization.

Furthermore, the significant preference for tests highlights a potential mismatch between student study habits and pedagogical innovation. This gap may reflect entrenched educational cultures that prioritize summative assessments over formative learning processes. Therefore, educators should consider implementing blended assessment strategies that combine traditional testing with interactive, reflective, and collaborative activities to promote comprehensive learning.

The findings also point toward the importance of motivation as a critical factor influencing engagement with learning tools. While satisfaction with the course was high, motivation to explore less traditional materials was limited. This suggests that enhancing intrinsic motivation, perhaps through gamification, personalized learning paths, or recognition of effort, could improve uptake of diverse tools.

Additionally, digital literacy levels among students may impact their willingness and ability to engage with various media types. Students unfamiliar with newer digital formats may gravitate towards traditional tools like tests. Thus, integrating digital skills training into course design may reduce barriers and promote more balanced tool utilization.

Finally, future research should explore the longitudinal effects of integrating varied educational tools with explicit training on learner autonomy. Such studies would clarify whether sustained exposure and support can shift student preferences and improve academic performance, providing a clearer roadmap for effective online course design.

CONCLUSIONS

This study revealed both positive and negative aspects of using an online course on Human Physiology. Positively, there was an increase in student satisfaction, greater interest in the subject, and a perceived enhancement in student autonomy. On the other hand, negative aspects included the lack of improvement in final test performance and underutilization of many of the course’s available tools. Tests were by far the most used resource, a finding that warrants further investigation to understand whether this preference reflects ingrained educational habits and if frequent testing can be strategically applied in other educational contexts.

Moreover, the disparity between high student satisfaction and the absence of measurable learning gains suggests that affective factors such as motivation and engagement, although important, may not directly translate into cognitive outcomes without intentional instructional design. This gap highlights the necessity of incorporating active learning strategies and formative assessments that foster deeper understanding, particularly in online environments where students must regulate their own learning processes.

Additionally, the limited use of interactive and diverse educational tools beyond tests indicates a potential misalignment between digital resource design and student learning preferences or behaviors. To mitigate this, educators and instructional designers should implement scaffolding techniques, guided activities, and personalized feedback to encourage meaningful interaction with all resources, thereby promoting a more comprehensive and effective learning experience.

Finally, challenges related to student autonomy and forum participation underscore the importance of ongoing support within online courses. Educational institutions should focus on training both students and instructors in digital literacy and self-directed learning skills while fostering community-building opportunities to encourage peer interaction. These measures are essential for maintaining engagement and maximizing the pedagogical benefits of online courses in complex disciplines like Human Physiology.

In conclusion, while online courses show significant potential to enhance teaching and learning, realizing their full benefits depends on thoughtful course design, targeted support, and continuous evaluation of student behaviors and outcomes. Addressing these factors will better align student experiences with learning objectives and ultimately improve academic performance in virtual learning environments.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the students to the realization of this project. We would like to thank Vanessa Ceglarek, Amanda Cunha Sarmento, Thalya Carvalho, Sandro Rauup and Leticia Fagundes.

GRANTS

No funding or grants were received for this research. Fernando Oliveira receives a scholarship from CNPq for his doctoral studies.

LIMITATIONS OF STUDY

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the dropout rate was high, with only 52.8% of enrolled students completing the final test, which may compromise the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the assessment instruments (pre- and post-tests) were not psychometrically validated, potentially affecting the reliability and validity of the measured student performance.

Furthermore, no statistically significant improvement was observed between pre- and post-test scores, suggesting that despite reported student satisfaction, the course may not have effectively promoted measurable learning gains. Low active participation in discussion forums limited opportunities for interaction and collaborative learning, which may have negatively influenced course effectiveness. Although innovative tools such as videos and comic strips were provided, student preference for traditional testing methods indicates a cultural resistance that was not fully overcome, possibly due to insufficient guidance and encouragement.

Finally, the convenience sampling approach restricts the generalizability of the results to broader populations. There was no control over external variables, such as time dedicated to study or other learning sources, making causal attribution of outcomes difficult. The absence of longitudinal follow-up limits understanding of the long-term impact of the course.

NOTES

The open-ended questions will be analyzed in a separate, dedicated study due to the complexity and depth of the responses.

REFERENCES

1 – BACICH, L., MORAN, J. Metodologias Ativas para uma Educação Inovadora. Brasil: Grupo A, 2017. 9788584291168. https://app.minhabiblioteca.com.br/#/books/9788584291168/. Access: 25 mar. 2022.

2 – BASEGIO, A. C. et al. Educação Ambiental e Construção de Aprendizagens: Um Olhar Bioecológico. TEXTURA-Revista de Educação e Letras, v. 20, n. 42, 2018.

3 – BEBER, Lílian Corrêa Costa, FIORIN, Pauline Brendler Goettems. Pesquisa e reflexão aliada ao ensino na graduação: ferramentas alternativas para trabalhar a anatomia e fisiologia humana. Biografia v. 12, n. 23, 2019.

4 – BENEVIDES, J. A. et al. Implementação De Metodologias Ativas Como Ferramenta Avaliativa Na Disciplina De Fisiologia Vegetal Em Tempos De Pandemia: Experiências E Desafios. HOLOS, v. 4, p. 1-16, 2021.

5 – BORGES, M. C., MIRANDA, C. H., SANTANA, R. C., BOLLELA, V. R. Avaliação formativa e feedback como ferramenta de aprendizado na formação de profissionais da saúde. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto), [S. l.], v. 47, n. 3, p. 324-331, 2014. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2176-7262.v47i3p324-331. https://www.revistas.usp.br/rmrp/article/view/86685. Access: 5 maio. 2023.

6 – BROSSI, MS G. C. A Avaliação Como Centro No Ensino Fundamental.

7 – CASIRAGHI, Bruna et al. O ensino superior num contexto sociocultural de desafios, 2022.

8 – CEA ÁLVAREZ, Ana María et al. Potenciar a autonomia através do feedback: propostas para uma aprendizagem híbrida no ensino superior. 2023.

9 – CORTELAZZO, A.L., FIALA, D.A.S., PIVA JR, D., PANISSON, L.S., RODRIGUES, M.R.J.B. Metodologias Ativas e Personalizadas de Aprendizagem: para refinar seu cardápio metodológico. Rio de Janeiro: Alta Books, 2018.

10 – D’ALPINO, P. H. P., et al. “Uso de Plataformas Integradoras de Ferramentas Tecnológicas e Pedagógicas em Ambiente Virtual de Aprendizagem em Profissões de Saúde.” Revista de Ensino, Educação e Ciências Humanas19.2 (2018): 168-176.

11 – DAS NEVES, Ben, MACHADO, Rui Seabra, CARPES, Pamela Billig Mello. DESIGN THINKING COMO ESTRATÉGIA PARA AUXILIAR NA APRENDIZAGEM DE UM CONCEITO COMPLEXO DE FISIOLOGIA. Anais do Salão Internacional de Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão, v. 10, n. 1, 2018.

12 – DINIZ, L. M. As Influências do Ciclo de Aprendizagem nos Cursos de Ensino a Distância: as Estratégias de Aprendizagem na Satisfação dos Alunos EaD. Editora Dialética, 2022. ISBN: 652522430697865224305

13 – DOLAN, E. L., COLLINS, J. P. We Must Teach More Effectively: Here Are Four Ways to Get Started. Molecular Biology of the Cell,v. 26(12), 2015. Doi: https://www.molbiolcell.org/doi/ abs/10.1091/mbc.e13-11-0675>. Access: 17 de março de 2022.

14 – GARCIA, P., S., BIZZO, N., FAZIO, X. Desafios da Formação Contínua a Distância para Professores de Ciências. Revista Iberoamericana de Educacion a Distância,Ecuador. San Cayetano Alto, v.17, n.2, 2014.

15 – KOEHLER, Cristiane, CARVALHO, Marie Jane S. Interação mútua e docência mediadora: Subsídios para avaliar a aprendizagem na educação online. SÁNCHEZ, J. Nuevas Ideas en Informática Educativa. Santiago, Chile: TISE, v. 8, p. 279-380, 2012.

16 – LOPES, Helder et al. A funcionalidade do processo pedagógico. Revista da Sociedade Científica de Pedagogia do Desporto, v. 1, n. 2, p. 54-65, 2013.

17 – MORAN, J. Metodologias Ativas Para Uma Aprendizagem Mais Profunda. In: BACICH, L.; MORAN, J. (org.). Metodologias Ativas Para Uma Educação Inovadora: Uma Abordagem Teórico-Prática. Porto Al MORÁN, J. Mudando a Educação com Metodologias Ativas. In: SOUZA, C. A.; MORALES, O. E. T. (org.). Convergências Midiáticas, Educação e Cidadania: Aproximações Jovens. Ponta Grossa: UEPG/PROEX, 2015. p. 15–33. (Mídias Contemporâneas, 2). http://www2.eca.usp.br/moran/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/mudando_moran. pdf. Access: 23 março 2022. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2018

18 – NASRE-NASSER, R. et al. Behind teaching-learning strategies in physiology: perceptions of students and teachers of Brazilian medical courses. American Physiology Society, 2022. Doi: 10.1152/advan.00134.2021.

19 – OLIVEIRA, P. R., OESTERREICH, S. A, ALMEIDA, V. L. Evasão na Pós-Graduação a Distância: Evidências de Um Estudo no Interior do Brasil. Educação e Pesquisa, v. 44, p. e165786-e165786, 2018.

20 – PARESCHI, C. Z., MARTINI, C. J. A Autonomia na EaD. Revista Educação em Foco, São Paulo, 2017.

21 – PEDROSA, R.A., NUNES, D. O Desafio da Evasão nos Cursos Superiores na Modalidade EaD,2019.

22 – TERRA, C. B. Ambiente Virtual Moodle Como Ferramenta de Apoio ao Ensino Presencial em Curso Técnico. 2018.

23 – VERAS, K. da C. B. B., TORRES, R. A. M., ALBANO, B. da S., GOMES, E. D. P., COSTA, I. G. From classrooms to virtual environments: Students’ perception of virtual classes as learning cyberspaces in the nursing course. Research, Society and Development, [S. l.], v. 12, n. 4, p. e3812440749, 2023. DOI: 10.33448/rsd-v12i4.40749. https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/40749. Access: 19 Apr. 2023.

24 – VIEIRA, V. M. A Importância do “Feedback” na Educação a Distância. Revista Primeira Evolução, v.1, n. 20, p. 97 – 107, 2021.

Table 1 – Student data on educational institution, gender and access to the course: courses 1, 2 and 3.

Figure Legends

Figure 01: Advantages offered by the online course compared to the traditional teaching: courses 1, 2 and 3.

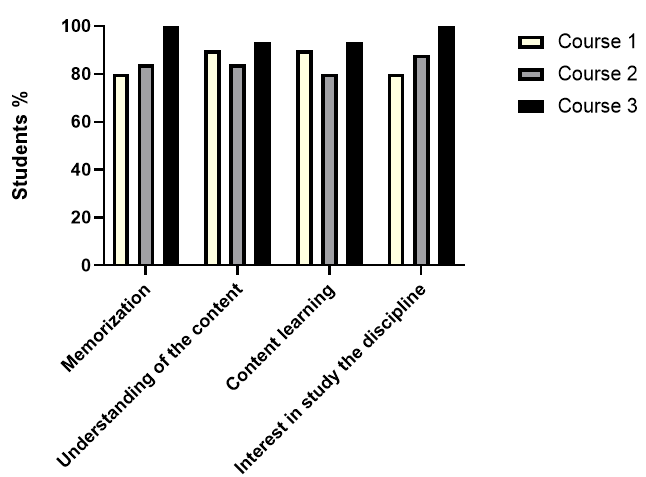

Figure 02: Contribution of the online course to the study of the discipline of Human Physiology: courses 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 03: Mean and standard deviation of student scores on the pre-test and final test: courses 1, 2 and 3. There was no statistical difference between the pre-test and the final test in any of the courses (students’ t test), nor was there a difference between the groups (one-way ANOVA).

Figure 04: Contribution of the course format to increase student autonomy: courses 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 05: Tools that most contributed to the learning process: courses 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 06: Number of views for each tool during courses 1, 2 and 3.

1Graduate Program in Biological Sciences: Physiology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-9405-2024

2Brazil Regional University of Cariri, Iguatu, Ceará, Brazil

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-9303-1858

3Department of Pharmacology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7929-1688

4Graduate Program in Biological Sciences: Physiology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2265-7332

Institution ID: https://ror.org/041yk2d64

Corresponding Author: Fernando Sérgio Oliveira, graduate program in Biological Sciences: Physiology, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.