REGISTRO DOI:10.5281/zenodo.10118991

Anderson de Oliveira Viana1

José Brasileiro Dourado Junior 2

RESUMO

A indústria do tabaco via, ano após ano, seus negócios encolherem, até que em 2004 foi desenvolvido o cigarro eletrônico, dando novo fôlego a esse mercado a partir da inovação que prometia retirar ou reduzir o vício dos adictos ao cigarro comum. Ao contrário, observou-se que os Dispositivos Eletrônicos para Fumar (DEF’s) não apenas não atingiam esses objetivos, como também os perigos de seu uso sequer estão bem definidos. O público jovem tem sido o maior consumidor dos DEF’s e, nesse contexto, evidenciou-se o aumento do uso entre estudantes, inclusive os da área da saúde. Assim, esse estudo propôs-se a desvendar o(s) principal(is) motivo(s) que levam a esse seleto público ao uso de DEF’s. Esse trabalho foi uma pesquisa de campo, observacional, exploratória e descritiva; foi desenvolvido um estudo do tipo transversal e quantitativo. As informações coletadas foram analisadas em bancos de dados e planilhas, entre os quais, o software Excel versão 2210, realizando-se análise descritiva. Correlacionou-se os resultados da Escala Razões Para Fumar Modificada traduzida para o português falado no Brasil adaptada para o cigarro eletrônico com os fatores motivacionais propostos pela literatura acerca da temática. Realizou-se em um Centro Universitário de João Pessoa-PB, durante o segundo semestre de 2022 através de formulário eletrônico, aplicado entre os estudantes de medicina da instituição, levando em consideração os critérios de inclusão e de exclusão, sendo iniciado após a aprovação em Comitê de Ética e Pesquisa. Coletou-se 274 amostras, atingindo um nível de confiança de 95% e margem de erro de 5%. Observou-se que 17,9% dos estudantes faziam uso do cigarro eletrônico. Evidenciou-se, entre outros dados, que 55,1% (ante 38,6% em outro estudo) dos estudantes já experimentaram cigarros eletrônicos, o que foi considerada uma taxa alta. Também, que 17,9% dos estudantes faziam uso regular desses dispositivos, número bastante expressivo, vez que praticamente um em cada cinco alunos usavam DEF’s, revelando aumento do uso de cigarros eletrônicos em adultos jovens, tendência já comprovada em outros estudos. Também, ao associar as respostas do instrumento para identificar os motivos mais preponderantes para o uso de DEF’s, não obstante tais razões serem de natureza multidimensional e a necessidade do uso desses dispositivos decorrerem de diversas facetas psicossociais dos indivíduos, o prazer para fumar despontou como fator motivador mais forte entre o grupo pesquisado, demonstrando a busca pela sensação de prazer percebida no início do uso da nicotina.

Palavras-chave: sistemas eletrônicos de liberação de nicotina; uso de cigarro eletrônico; vaping; motivação; estudantes de medicina.

ABSTRACT

The tobacco industry saw, year after year, its business shrink, until in 2004 the electronic cigarette was developed, giving new life to this market from the innovation that promised to remove or reduce the addiction of addicts to ordinary cigarettes. On the contrary, it was observed that Electronic Smoke Devices (ESDs) not only did not reach these goals, but also that the dangers of their use are not even well defined. The young public has been the biggest consumer of ESDs and, in this context, there has been an increase in use among students, including those in the health area. Thus, this study aimed to unravel the main reason(s) that lead this select public to the use of ESDs. This work consisted of observational, exploratory, descriptive and field research; a cross-sectional and quantitative study was developed. The collected information was analyzed in databases and spreadsheets, including Excel version 2210 software, performing descriptive analysis. The results of the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes were correlated with the motivational factors proposed by the literature on the subject. It was carried out at a University Center in João Pessoa-PB, during the second half of 2022 through an electronic form, answered by some of the institution’s medical students, taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria, starting after approval in the Ethics and Research Committee. A total of 274 samples were collected, reaching a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. It was observed that 17.9% of students used electronic cigarettes. It was shown, among other data, that 55.1% (compared to 38.6% in another study) of students had already tried electronic cigarettes, which was considered a high rate. Also, that 17.9% of the students made regular use of these devices, a very expressive number, since practically one in every five students used ESDs, revealing an increase in the use of electronic cigarettes in young adults, a trend already proven in other studies. Also, when associating the answers of the instrument to identify the most predominant reasons for the use of ESDs, despite such reasons being of a multidimensional nature and the need for the use of these devices arising from different psychosocial facets of individuals, the pleasure of smoking emerged as the strongest motivator factor among the researched group, demonstrating the search for the sensation of pleasure perceived in the beginning of the use of nicotine.

Keywords: electronic nicotine delivery systems; electronic cigarette use; vaping; motivation; medical students.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

EC Electronic cigarette ESDs Electronic Smoking Devices USA United Sates of America MH Ministry of Health WHO World Health Organization PB State of Paraíba – Brazil PROAC Academic Pro-Rectory TFIC Term of Free and Informed Consent UNIPÊ João Pessoa University Center

PRESENTATION

This Final Paper was presented in the form of a scientific article.

SUMMARY

1 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………………… 09 2 GOALS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11

2.1 General goal ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11

2.2 Specific goals …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 11

- MATERIALS AND METHODS ……………………………………………………………………… 12

- Outline of study ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 12

- Place and period of study ………………………………………………………………………………… 12

- Population and sample …………………………………………………………………………………….. 12

- Inclusion and excluison criteria ……………………………………………………………………….. 12

- Defining variables……………………………………………………………………………………………. 13

- Data collection instruments …………………………………………………………………………….. 13

- Data collection procedure ………………………………………………………………………………… 14

- Data analysis …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14

- Ethical aspects ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14

- RESULTS E DISCUSSION………………………………………………………………………………16

- CONCLUSIONS………………………………………………………………………………………………28

REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………………………………..29

ATTACHMENT A – MODIFIED REASONS FOR SMOKING SCALE

TRANSLATED INTO BRAZILIAN PORTUGUESE……………………………………….31

ATTACHMENT B – MODIFIED REASONS FOR SMOKING SCALE TRANSLATED INTO BRAZILIAN PORTUGUESE ADAPTED FOR ELECTRONIC

CIGARETTES…………………………………………………………………………………………………33

ATTACHMENT C – MOTIVATIONAL DOMAIN SCALE RELATED TO MODIFIED REASONS FOR SMOKING SCALE TRANSLATED INTO

BRAZILIAN PORTUGUESE…………………………………………………………………………..35

1 INTRODUCTION

For decades, tobacco has been identified as a major barrier to public health at a global level. Faced with this somber reality, there have been many efforts in recent years to change or definitively eradicate this structural, political and even social dynamic that sustains the tobacco epidemic. There have been initiatives in this direction, such as studies calling on society to, for example, have a world without tobacco by 2040, aiming at an ideal in which less than 5% of the world’s adult population would use tobacco, which would be socially desirable, technically feasible and it might even become politically practical (BEAGLEHOLE et al., 2015).

The enthusiasm in the pursuit of putting an end to this worldwide smoking scene was palpable: in most countries monitored by the World Health Organization (WHO), like the United States (USA) and Europe, the number of smokers decreased. However, in 2004 the tobacco industry introduced the electronic cigarette, a battery-powered metallic device that vaporizes a nicotine-laced liquid, initially becoming popular with those trying to quit smoking (PURKAYASTHA, 2013).

Recent research has indicated that rates of e-cigarette use have been increasing quite consistently since 2016 and exponentially from 2019 in the US (SCHULENBERG et al., 2020). Studies have also indicated that the proportion of young adults who have started using electronic devices for smoking (ESDs) is almost twice as high in relation to adolescents (PERRY et al., 2018).

Unfortunately, we have more and more scientific evidence pointing to e-cigarettes as carriers of significant health risks. There is also concrete evidence of an increased risk rate for respiratory diseases and the development of cardiovascular diseases (KEITH, 2021; OVERBEEK et al., 2020).

In this context, it is important to investigate the reasons that lead young adults to acquire the habit of using electronic cigarettes. Even more: the reasons that lead students in medical training to smoke ESD’s, despite having medical knowledge about scientific evidence of the risks provided by electronic cigarettes.

This study investigated the reasons for the use of ESDs by medical students at a private teaching institution in Paraíba, in the second half of 2022.

Electronic cigarettes have been seen more and more among friends, which shows that the proportion of experimentation with nicotine vaporizers has increased, especially among young people. The university environment seems to be becoming a favorable place for the dissemination of ESDs. Faced with this reality, researchers became interested in understanding the reasons that lead students to smoke electronic cigarettes.

In this sense, Oliveira et al. (2018) published an analysis of data collected through questionnaires on the level of EC knowledge and experimentation among students at a Brazilian university and found that 37% of students knew the product, while in the national prevalence this value is 35%. This percentage makes it possible to perceive that the public of the present study is relevant, mainly because it is aimed at a group of students in the health area.

The evolution of ESDs has included in its portfolio a multitude of flavors and styles of devices, thus having a range of new and attractive products. Added to this, the tobacco industry has always sought to innovate with products that are visually more attractive, socially more accepted and apparently safer (AHMAD; DUTRA, 2019).

However, that product that initially appeared with the proposal of reducing addiction to nicotine started to prove itself fruitless in the face of attempts to abandon the addiction and, even more, to recapture former smokers for addiction, as well as to include in their customers the so-called nicotine virgins, mostly young adults (KALKHORAN; GLANTZ, 2016; LOUKAS, 2018).

Faced with this grim scenario, there are few studies that have sought scientific evidence of the reasons behind the use of electronic cigarettes by students in general and even fewer with a focus on medical students. Most of the time, research proposes, mainly, to assess the prevalence of regular cigarette use. Additionally, there are few studies of this type regarding electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS).

Therefore, this research is of great importance due to its direction in order to evaluate the reasons behind the consumption of electronic cigarettes by medical students, since the harmful effects to health related to the use of ECs, especially the long-term consequences, are not fully understood, although there is evidence of respiratory, cardiovascular and immune compromise (KEITH; BHATNAGAR, 2021).

Therefore, in addition to this study providing new information on this topic, institutions can design means of awareness that are better targeted at this public and users in general, aimed at educating and indicating where quality information on the subject can be obtained.

2 GOALS

2.1 General goal

To identify the main reasons behind the use of electronic cigarettes by medical students.

2.2 Specific goals

To check if medical students are consuming electronic cigarettes due to nicotine addiction.

To check whether friendships are influencing the increase in use.

3 MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 Study outline

A field, observational, exploratory and descriptive research was developed. It was characterized as a cross-sectional and quantitative study.

3.2 Place and period of study

The research was carried out in a University Center in João Pessoa, spanning a period from September to October 2022.

3.3 Population and sample of study

The population was restricted to 945 medical students from a higher education institution, from first-year to last-year students. Sampling was performed nonprobabilistically for convenience, meeting the entry criteria. We sought a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, totaling a sample of up to 274 volunteers. The 274 samples were reached in this study.

3.4 Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

To be eligible to participate in the research, the volunteer should:

- Be regularly enrolled in the Medicine course at the University Center chosen for the study;

- Be at least 18 (eighteen) years old and;

- Agree to voluntarily participate in the research. To this end, he signed the Free and Informed Consent Term – FICT (ATTACHMENT A).

Students who did any of the following were excluded from the survey:

- Did not answer the questionnaire completely or;

- At any time, withdrew from continuing to participate in the survey, not sending the form responses.

3.5 Defining the variables

The study focused on seven variables – one quantitative and six qualitative – that helped and guided the research in achieving its objectives.

The only quantitative variable, age, was evaluated in years and evaluated the mode, mean and median age of medical students at the university who used ESDs.

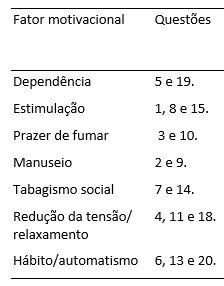

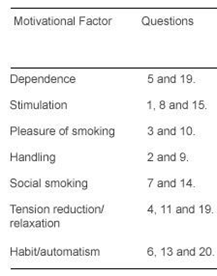

Regarding the variables “Use of ESDs”, “Reasons for using ESDs”, “Dependence”,

“Pleasure of smoking’, “Tension reduction/relaxation”, “Social smoking”, “Stimulation”, “Habit/automatism”, “Handling of ESDs”, they were chosen because they compose the motivational domains present in the questionnaire that was applied.

Chart 1 – Definition of variables and their types

Variables Type Age (years) Quantitative Sexo Qualitative Use of ESD’s Resons for using ESDs Dependence Pleasure of smoking Tension reduction/relaxation Social smoking Stimulation Habit/automatism Handling of ESDs

Source: Author, 2022.

3.6 Data collection instruments

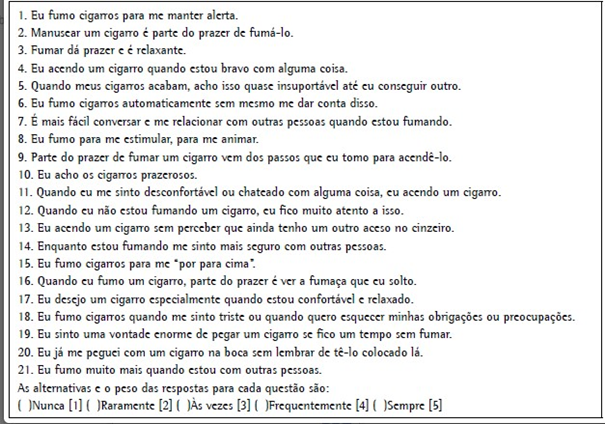

For data collection, we applied the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian Portuguese (ATTACHMENT A) and adapted it so that the questions were better suited to the use of electronic cigarettes. This scale was originally proposed by Horn & Waingrow in 1966 and later modified and translated into Portuguese (SOUZA, et al., 2009a).

3.7 Data collection procedures

An electronic form was created (ATTACHMENT B) and addressed to the various medical classes at the chosen University Center. By accessing the form link, the volunteer participant had access to the FICT, became aware of the research terms and, after accepting them, accessed the questions. Initially, the volunteer answered questions regarding gender, age and what semester and year they belong to in the medicine course, and completed a questionnaire regarding the use of alcohol, drugs, common cigarettes, and ESDs. Then, if you use ESDs, you accessed the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated and adapted into Brazilian Portuguese, where you answered questions according to the degree of each option, with the following alternatives available: never, rarely, sometimes, often or always (SOUZA, et al., 2009a).

3.8 Data analysis

All information about the subjects and the variables collected were entered and stored in a database electronically, using Excel version 2210 spreadsheet software to formulate graphs and tables, and also with the help of other software in the Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2019 package. With these methods, it was possible to analyze the data statistically, in a descriptive and exploratory way, calculating variables such as mean, mode, median.

Also, the results of applying the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into

Brazilian Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes were correlated with the Motivational Domains chart (ATTACHMENT C), which shows a high degree of agreement between motivational factors and their respective questions (SOUZA et al., 2009b).

3.9 Ethical aspects

Throughout the process of this research, there was no discrimination in the selection of individuals or exposure to unnecessary risks. This research was approved by the Ethics and Research with Human Beings Committee (CEP-UNIPÊ) of the University Center of João Pessoa – UNIPÊ and data collection only started after this approval, whose CAAE is registered under nº 60652122.0.0000.5176, and opinion number 5,692,478, which complies with the Guidelines and Norms for Research involving human beings, provided for in Resolution No. 466 of 2012 of the National Health Council in Brazil and Resolution No. 510/2016 of the National Health Council in Brazil.

Data collection for this study was only carried out after signing the Free and Informed Consent Term by the volunteers. We also value the protection of vulnerable groups, treating everyone with respect for their dignity and autonomy, and we have always sought to defend them in their vulnerability.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify the main reasons for the use of electronic cigarettes by medical students. To this end, the pattern of consumption of ESDs was observed in medical students from a respected higher education institution in the state of Paraíba in order to better understand the reasons that led them to use these devices.

It was an observational, exploratory and descriptive field research, conducted crosssectionally and quantitatively.

Data collection, initiated after approval by the specific Ethics and Research with Human Beings Committee, was carried out between September and October 2022, with nonprobabilistic sampling for convenience, reaching the ideal sample of 274 volunteers among the 945 medical students regularly enrolled at the time at the University Center object of study.

It was found that 64.6% (n = 177) of the volunteers were female, 35% (n = 96) were male and 0.4% (n = 1) declared themselves to be non-binary. With regard to the city of origin of the students who responded to the survey, it was observed that 56.6% (n = 155) were born in João Pessoa – PB, 8% (n = 22) were born in Natal – RN, 3.3 % (n = 9) were born in Recife – PE and 32.1% (n = 88) were from other cities in Brazil.

Regarding the age of the participants in this study, an average of 24.68 years was observed, with a standard deviation of 5.85 and a mode of 22 years, representing 16.8% (n = 46) of the volunteers. The second most prevalent age was 23 years old, with 13.9% (n = 38). Also, it is important to note that the age group from 18 to 27 years old corresponds to 79.9% (n = 219) of the amount studied, therefore, a population composed essentially of young adults, although the student body analyzed also had a considerable portion of older students, as discussed later.

See Table 1 (shown below) presenting the descriptive statistics of the sample, about which some considerations were made below.

Table 1 – Age: descriptive statistics – João Pessoa – 2022

Result Average 24,68 Standad error 0,354 Median 23 Mode 22 Standard deviation 5,856 Sample variance 34,298 Kurtosis 2,5247 Skewness 1,6815 Interval 32 Minimum 18 Maximum 50 Sum 6763 Count data 274 Confidence level (95,0%) 0,6965

Source: Author, 2022.

It is observed that the average age of the undergraduate students of Medicine who participated in the study is close to the national average obtained in 2014, that is, 24.5 years, which is also in line with other studies, such as the research carried out by the National Association of Directors of Higher Education Institutions (2016). On the other hand, it was also seen that 16.42% (n=45) of students are aged 30 or more, which can be understood as a search for better future socioeconomic conditions, either through inclusion in the job market or even a career change, since the medical professional is considered to have one of the most profitable professions nationwide (VERA et al., 2020).

Furthermore, it was noted there existed a predominance of females in the studied sample. This fact was confirmed in other previous surveys, which even showed a growing trend in female participation in higher education, despite the national composition of the population showing proportions that, even while demonstrating a slight female prevalence, remained at stable levels over the years. years, as assessed by the National Association of Directors of Higher Education Institutions (2019).

When asked about regular cigarette use, 96% (n = 263) denied using it, while 4% (n = 11) responded positively to the question. When it comes to other drugs, such as marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy, 9.1% (n = 25) claimed to use, while 90.9% (n = 249) denied using any of these substances.

In a recent study (LISBOA; OLIVEIRA, 2021) carried out at the Evangelical

University of Goiás, the prevalence of behavioral and biological factors of cardiovascular risk in medical students was analyzed, where it was found that 5.2% of students used tobacco, which is close to the 4% regular cigarette users seen in this survey.

Regarding the use of electronic devices for smoking (ESDs), 82.1% (n = 225) responded negatively, while 17.9% (n = 49) reported using electronic cigarettes. Of these, when asked about the amount of days a week they use the device, 42.9% (n = 21) declared using it less than 1 day a week (since they do not use it every week); 10.2% (n = 5) declared using it once a week; 14.3% (n = 7) stated using it two to three times a week; 4.1% (n = 2) use it four to five times a week; and 28.6% (n = 14) use electronic cigarettes six or more times a week.

When responding about the frequency of use on the days of use of ESDs, 20.4% (n = 10) declared using it once or twice on the days of use; 20.4% (n = 10) reported using it three to five times a day; and 59.2% (n = 29) stated that, on days of use, they smoke six or more times.

In another survey, carried out in 2019, the rate of electronic cigarette users was more moderate than that recorded here. There, about 12% of undergraduate students in Dentistry at the Federal University of Santa Catarina reported using or having used electronic cigarettes, and the highest percentage was found in the group of freshmen in the course, which corroborates the understanding that the young adult population is the one that has been most seduced by electronic cigarettes and there seems to be a trend towards an increase in prevalence in increasingly younger age groups (GUCKERT, 2019).

After being questioned about the use of ESDs, among non-users, 98.2% (n = 221) of participants stated that they had already seen friends and fellow medical students from the same study center using electronic cigarettes, compared to 1, 8% (n = 4) who said they had never seen it; 45.3% (n = 102) have tried it at some point and 58.2% (n = 131) feel uncomfortable when they see other people smoking.

Crossing data from current users 17.9% (n = 49) and those who have tried it, but are not in use (n = 102 out of 225), we arrive at the amount of 55.1% (n = 151) of medical students who have at least tried electronic cigarettes.

It is denoted from the data that there is a significant number of medical students who use electronic cigarettes, reaching close to 1/5 of the students, that is, practically 1 in 5 medical students used ESDs. Even more demeaning was the fact that, according to the survey data, more than half of medical students 55.1% (n = 151) had already tried at least one electronic cigarette.

A survey of 342 volunteers carried out in 2021 in health courses at a University in Recife in which the percentage of experimentation with electronic cigarettes among students was found to be 38.6%, which is also characterized as a high rate of experimentation (REIS et al., 2021).

The concept of smoking has undergone profound changes over time. In the 1960s, smoking, until then socially accepted, was considered a habit. In 1970 it started to be seen as dependence, a decade later there was talk of smoking as an addiction and in the 90s the first clinics for smokers appeared. In recent years, institutions of great scientific prestige have highlighted the evidence on nicotine dependence (CARMO; ANDRÉS-PUEYO; LÓPEZ,

2005).

Accordingly, smoking has been considered a public health problem for decades, despite a decrease in its prevalence in recent years. However, a considerable number of young adults still experiment with various means of tobacco consumption, which makes them vulnerable to initiation and, consequently, often to dependence. (OLIVEIRA, 2016).

The 17.9% (n = 49) who answered affirmatively as to being users of ESDs were automatically forwarded by the platform to the instrument, that is, the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes (Attachment B) and, below, their respective answers were listed in Table 2.

Table 2 – Answers to the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian

Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes – João Pessoa – 2022

Question Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

- 40 81,6% 4 8,2% 3 6,1% 1 2,0% 1 2,0%

- 18 36,7% 5 10,2% 13 26,5% 8 16,3% 5 10,2%

- 4 8,2% 0 0,0% 15 30,6% 17 34,7% 13 26,5%

- 18 36,7% 7 14,3% 13 26,5% 8 16,3% 3 6,1%

- 30 61,2% 6 12,2% 7 14,3% 2 4,1% 4 8,2%

- 22 44,9% 6 12,2% 9 18,4% 7 14,3% 5 10,2%

- 30 61,2% 10 20,4% 4 8,2% 4 8,2% 1 2,0%

- 23 46,9% 6 12,2% 14 28,6% 5 10,2% 1 2,0%

- 35 71,4% 8 16,3% 4 8,2% 2 4,1% 0 0,0% 10 3 6,1% 3 6,1% 11 22,4% 23 46,9% 9 18,4%

- 20 40,8% 8 16,3% 8 16,3% 8 16,3% 5 10,2%

- 25 51,0% 11 22,4% 5 10,2% 7 14,3% 1 2,0%

- 47 95,9% 2 4,1% 0 0,0% 0 0,0% 0 0,0%

- 38 77,6% 7 14,3% 3 6,1% 1 2,0% 0 0,0%

- 37 75,5% 6 12,2% 4 8,2% 2 4,1% 0 0,0%

- 17 34,7% 13 26,5% 13 26,5% 5 10,2% 1 2,0%

- 14 28,6% 7 14,3% 17 34,7% 8 16,3% 3 6,1%

- 25 51,0% 8 16,3% 9 18,4% 6 12,2% 1 2,0%

- 19 38,8% 6 12,2% 12 24,5% 9 18,4% 3 6,1%

- 43 87,8% 3 6,1% 3 6,1% 0 0,0% 0 0,0%

- 6 12,2% 5 10,2% 14 28,6% 14 28,6% 10 20,4%

Source: Author, 2022.

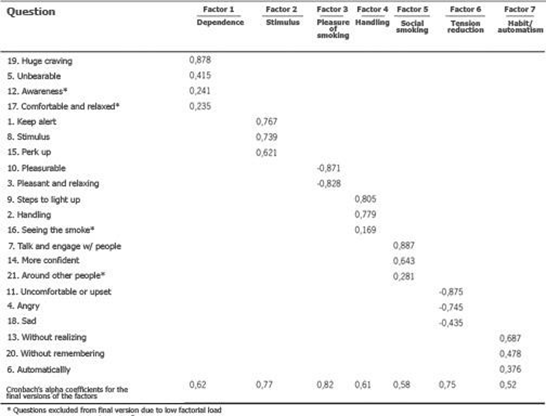

With regard to the instrument validated as the basis of the instrument adapted for this research, studies performed factor analysis of the scale used, thus identifying seven motivational factors, which would explain 62.4% of the total variance of the responses obtained. For information purposes, the composition of these factors was brought to this research (Table 3) and the values of the factor loadings obtained, listed in the table below, where the denomination already used by the literature for each of the factors can be seen. The levels of internal consistency of the generated factors are also declined, obtained from Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (SOUZA et al., 2009b).

Table 3 – Composition and factor loading of the factors identified in the Brazilian version –

João

Pessoa – 2022

Source: SOUZA et al. (2009b).

Translation: Marina Mentor Santos

The exclusion of questions that had a factorial load of 0.3 or less was considered, culminating in four questions being excluded from the analysis. Therefore, questions 12, 16, 17 and 21 were disregarded, since they did not demonstrate sufficient influence on their respective motivational factors. Each of the motivational factors was named according to the original terminology as seen in the literature. (SOUZA et al., 2009b).

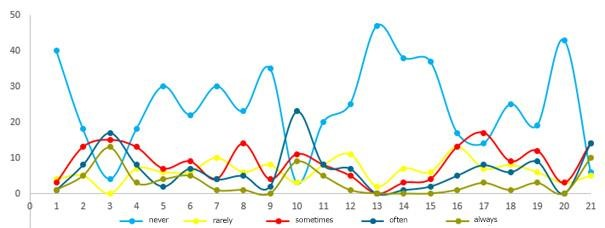

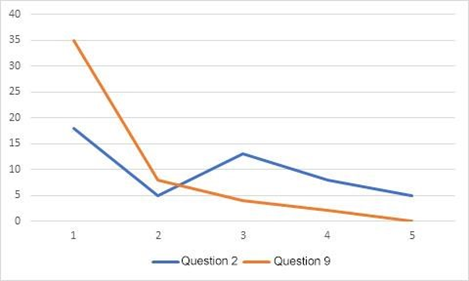

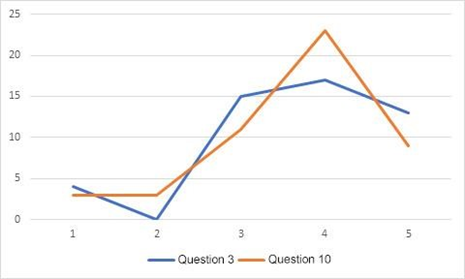

The responses were, then, associated to the instrument (Table 2) in accordance to the seven motivational factors, generating the graphs below (Graph 1), which consolidates all the answers obtained in the scale.

Graph 1 – Representation of all responses to the applied scale – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

It is observed, in the graph above, that in questions 3, 10 and 21 the number of answers considered positive to the question (“sometimes”, “often” and “always”) were higher than those considered negative to the question (“rarely” and “never”), denoting in these points the main foci that impact the reasons for smoking.

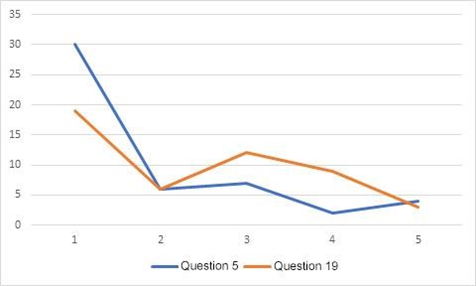

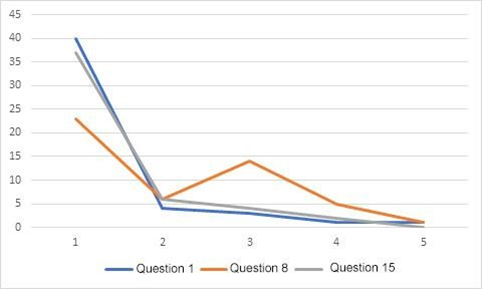

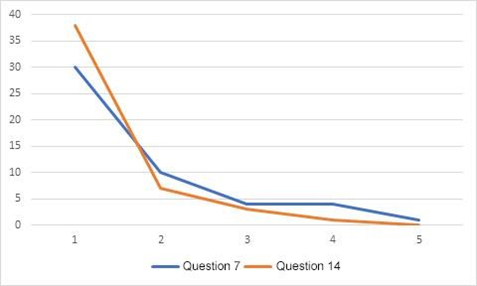

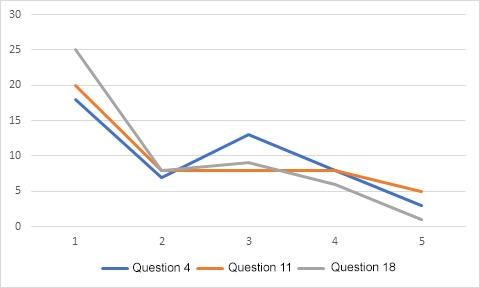

The next six graphs below correspond, respectively, to motivational factors 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7, where the same trend of more negative answers to the respective questions that make up the factors mentioned was observed, with “rarely” and “never” answers prevailing compared to the number of answers given in “sometimes”, “often” and “always”, generating graphs with decreasing lines in general.

Thus, it is observed that motivational factors 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 (dependence, stimulation, handling, social smoking, tension reduction/relaxation and habit/automatism) did not prove to be relevant factors for the population studied. Therefore, although loaded with a certain influence on the use of ESDs, such factors were not considered as preponderant reasons for medical students to use electronic cigarettes.

2 tor 1: Dependence – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

Graph 3 – Factor 2: Stimulus – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

4 tor 4: Handling – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

Graph 5 – Factor 5: Social smoking – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

6 tor 6: Tension reduction /relaxation– João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

Graph 7 – Factor 7: Habit/automatism– João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

Graphs 1 to 7 above show the association between the frequency of responses according to the graph legend and the number of affirmative answers to questions related to motivational factors: dependence, stimulation, handling, social smoking, tension reduction/relaxation and habit/automatism. The exact numbers in the graph were illustrated in Table 1, presented above. It appears, based on the analysis of the graphs, that such factors

were not shown to be the predominant reason for the use of electronic cigarettes in the researched population.

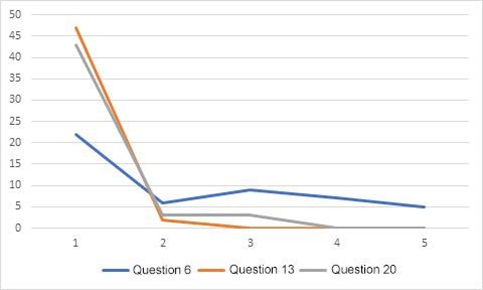

Graph 8 – Factor 3: Pleasure of smoking – João Pessoa – 2022

Source: Author, 2022.

Legend: 1. Never. 2. Rarely. 3. Sometimes. 4. Often. 5. Always.

Graph 8 shows the association between the number of affirmative answers to questions 3 and 10 in relation to frequency, as shown in the caption. The exact numbers in the graph were shown in Table 1, presented above. It appears, from the analysis of the chart, that the motivational factor “pleasure of smoking” was a reason for the use of ESDs since there is a predominance of affirmative answers to questions that include the “pleasure of smoking” factor, totaling 91.8 % (n = 45) of responses considered positive (“sometimes”, “often” and “always”) to question 3, and 87.7% (n = 43) of responses considered positive to question 10.

Thus, factor 3 “Pleasure of smoking” is the most prevalent among the 7 factors analyzed, which is the most prevalent reason for smoking ESDs by medical students in the present study.

Several self-administered chemical products are believed to trigger a rewarding action in the cerebral cortex through the dopaminergic pathway. Many of them produce dependence by causing cerebral dopaminergic release, causing their consumers to adopt repetitive selfadministration behaviors in order to achieve this rewarding benefit.

In this context, chemical dependence on nicotine occurs due to exacerbated stimulation of the reward system in the central nervous system, which initially triggers a feeling of pleasure and, subsequently, of relaxation. After some time of use, successive stimuli will generate tolerance to nicotine, or if the amount of the substance in the body is considerably reduced, a state of abstinence is likely to develop, which can present very exacerbated symptoms of anxiety (DOURADO JÚNIOR, 2013).

It is known today that smoking goes far beyond physical dependence on nicotine, since it was believed that the physical-chemical characteristics and psychoactive interactions of nicotine were most responsible for nicotine dependence. However, there is evidence that the reasons for smoking are multidimensional in nature. Therefore, smoking is currently considered to go far beyond physical dependence on nicotine, since such dependence encompasses factors beyond physical addiction, covering several psychosocial facets of the individual (CARMO; ANDRÉS-PUEYO; LÓPEZ, 2005).

Regarding limitations, time is described as an impeding factor for further statistical analysis, although, as demonstrated before, previous factor analyzes of the instrument demonstrated applicability and cohesion between its results.

Also, although a relevant sample was attained, reaching very significant confidence numbers, no other studies were found in the literature that use the same instrument in an adapted way to investigate the reasons for using electronic smoking devices. However, the results were compared with other similar studies (e.g., based on regular cigarettes), in which a certain equivalence could be observed.

5 CONCLUSION

In light of the objectives of this study, it can be concluded that, despite the participation of several motivational factors to some degree, the pleasure of smoking was identified as the main reason for smoking electronic cigarettes among medical students. That said, the precise identification of distinctive factors that induce people to smoke electronic cigarettes brings the possibility of contributing to the development of public policies for the prevention and control of smoking of ESDs, as well as the development of personalized strategies for the cessation of this contemporary form of smoking.

With regard to the applied instrument, there could be more socially pleasant answers, which happen when the respondent wants to present an image that is somehow better than reality, a fact that can occur in questions with multiple choices, in which the answers leave room for interpretation, which is when social and psychological issues can trigger response bias.

The results obtained in this study are not intended to elaborate resolute, unquestionable and finished outcomes. Diversely, it is believed and expected that this research will have the power to encourage new complementary and comparative work on the subject, not being restricted solely to the population studied here, but also covering other student spheres or even the general population.

Thus, the aim is to continue the inexorable role of scientific research in terms of obtaining and disseminating solid and quality information, aiming at the common good.

REFERENCES

AHMAD, I; DUTRA, L. Imitating waterpipe: Another tobacco industry attempt to create a cigarette that seems safer. Addict Behav. 2019. Available at:

<https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30366727/>. Accessed on: 10 April 2022.

ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DOS DIRIGENTES DAS INSTITUIÇÕES DE ENSINO

SUPERIOR. IV Pesquisa Do Perfil Socioeconômico e Cultural dos Estudantes de Graduação das Instituições Federais de Ensino Superior Brasileiras. Uberlândia, 2016. Available at: <https://www.andifes.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/IV-PesquisaNacional-de-Perfil-Socioeconomico-e-Cultural-dos-as-Graduandos-as-das-IFES.pdf>. Accessed on: 28 Nov. 2022.

ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DOS DIRIGENTES DAS INSTITUIÇÕES DE ENSINO

SUPERIOR. V Pesquisa Nacional de Perfil Socioeconômico e Cultural dos (as) Graduandos (as) das IFES. Brasília, 2019. Available at: https://www.andifes.org.br/?p=88796) <https://www.andifes.org.br/wpcontent/uploads/2021/07/Clique-aqui-para-acessar-o-arquivo-completo.-1.pdf>. Accessed on: 27 Nov. 2022.

BEAGLEHOLE, R.; et. al. A tobacco-free world: a call to action to phase out the sale of tobacco products by 2040. The Lancet, 2015. Available at:

<https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673615601337>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

CARMO, J; ANDRÉS-PUEYO, A; LÓPEZ, E. The evolution in the concept of smoking. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, v. 21, p. 999-1005, 2005. Available at:

<https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/t8f6fpVrnT6tHr48HrthkCn/abstract/?lang=en>. Accessed on: 26 Nov. 2022.

DOURADO JÚNIOR, J. Prevalência de tabagismo entre os profissionais do Complexo Psiquiátrico Juliano Moreira em João Pessoa-PB. 2013. Monografia. (Residência médica na área de psiquiatria). UFPB, João Pessoa, 2013.

GUCKERT, E.; et. al. Nível de conhecimento dos estudantes do curso de Graduação em Odontologia da UFSC sobre cigarros eletrônicos. 2019. Available at:

https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/201622. Accessed on: 10 Nov. 2022.

KALKHORAN, S; GLANTZ, S. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med, 2016. Available at: <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26776875/>. Accessed on: 10 April. 2022.

KEITH, R; BHATNAGAR, A. Cardiorespiratory and Immunologic Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. Curr Addict Rep, 2021. Accessed on: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-02100359-7>. Acesso em: 07 April 2022.

LISBOA; OLIVEIRA, R. Análise e prevalência dos fatores comportamentais e biológicos de risco cardiovascular em acadêmicos de medicina. Rev. Educ. Saúde. Goiás, 2021. Accessed on:<https://scholar.archive.org/work/vekkejqkxffgjdpub7w7rvs2cy/access/wayback/http://peri odicos.unievangelica.edu.br/index.php/educacaoemsaude/article/download/6043/4307/>. Acesso em: 30 Nov. 2022.

OLIVEIRA, L. Experimentação e uso de cigarro eletrônico e narguilé entre universitários. 2016. 91 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências da Saúde) – Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, 2016. Available at:

<https://repositorio.bc.ufg.br/tede/handle/tede/6721>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

OLIVEIRA, W. et al. Electronic cigarette awareness and use among students at the Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia [online]. 2018, v. 44, n. 5, pp. 367-369. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562017000000229>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

OVERBEEK, D. et al. A review of toxic effects of electronic cigarettes/vaping in adolescents and young adults, Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 2020. Available at:

<https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/10408444.2020.1794443?scroll=top&nee dAccess=true>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

PERRY, C. et al. Youth or Young Adults: Which Group Is at Highest Risk for Tobacco Use Onset? J Adolesc Health, 2018. Available at: <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30001826/>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

PURKAYASTHA, D. BAT ramps-up E-cigarette expansion as sales go up in smoke. International Business Times, 2013. Available at: <https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/britishamerican-tobacco-e-cigaretteprofit-vype-495893>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

REIS, M. et al. Avaliação do perfil epidemiológico e de consumo de estudantes usuários de cigarro eletrônico dos cursos de saúde de uma faculdade da cidade de Recife. 2021.

Available at:

<http://higia.imip.org.br/bitstream/123456789/794/1/Artigo_PIBIC%202020%202021_Bruna %20Maciel.pdf>. Accessed on: 25 Nov. 2022.

SCHULENBERG, J. et al. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: volume II, College Students and Adults Ages 19-60. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2020. Available at:

<https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED608266.pdf>. Accessed on: 08 April 2022.

SOUZA, E. et al. Escala Razões para Fumar Modificada: tradução e adaptação cultural para o português para uso no Brasil e avaliação da confiabilidade teste-reteste. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia [online]. 2009, v. 35, n. 7, pp. 683-689. Available at:

<https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132009000700010>. Accessed on: 01 May 2022.

SOUZA, E. et al. Estrutura fatorial da versão brasileira da escala razões para fumar modificada. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira [online]. 2009, v. 55, n. 5, pp. 557562. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302009000500019>. Accessed on: 27 Nov. 2022.

ATTACHMENT A – Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated to Brazilian Portuguese (Original and English Version

Source: SOUZA, et al., (2009a).

English Translation:

I smoke cigarettes to keep alert. Handling a cigarette is art of the enjoyment of smoking it. Smoking cigarettes is pleasant and relaxing. I light up a cigarette when I feel angry about something. When I run out of cigarettes, I find it almost unbearable until I can get another one. I smoke cigarettes automatically without even being aware of it. It’s easier to talk and engage with other people when I am smoking a cigarette. I smoke to get some stimulus, to perk myself up. Part of the pleasure of smoking a cigarette comes from the steps I take to light it. I find cigarettes pleasurable. When I feel uncomfortable or upset about something, I light up a cigarette When I am not smoking a cigarette, I am very aware of that fact. I light up a cigarette without realizing there is still one burning in the ashtray. I feel more confident around people when I am smoking. I smoke cigarettes to “perk up”. When I smoke a cigarette, part of the enjoyment comes from watching the smoke as I exhale. I desire a cigarette especially when I am comfortable and relaxed. I smoke a cigarette when I am sad or when I want to forget my obligations and worries. I get a huge craving for a cigarette when I haven’t smoked in a while. I have found myself with a cigarette in my mouth without remembering putting it there. I smoke much more when around other people The alternatives and their respective weight are: ( ) Never [1] ( ) Rarely [2] ( ) Sometimes [3] ( ) Often [4] ( ) Always [5]

Source: SOUZA, et al., (2009a).

Translation: Marina Mentor Santos

ATTACHMENT B – Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes.

- Eu fumo cigarro eletrônico para me manter alerta.

- Manusear um cigarro eletrônico é parte do prazer de fumá-lo.

- Fumar cigarro eletrônico dá prazer e é relaxante.

- Eu ativo um cigarro eletrônico quando estou bravo com alguma coisa.

- Quando a carga de meu cigarro eletrônico acaba, acho isso quase insuportável até que eu consiga recarregá-lo.

- Eu fumo cigarros eletrônicos automaticamente sem mesmo me dar conta disso.

- É mais fácil conversar e me relacionar com outras pessoas quando estou fumando cigarro eletrônico.

- Eu fumo cigarro eletrônico para me estimular, para me animar.

- Parte do prazer do fumar um cigarro eletrônico vem dos passos que eu tomo para ativá-lo.

- Eu acho os cigarros eletrônicos prazerosos.

- Quando eu me sinto desconfortável ou chateado com alguma coisa, eu ativo um cigarro eletrônico.

- Quando eu não estou fumando um cigarro eletrônico, eu fico muito alerta a isso.

- Eu ativo um cigarro eletrônico sem perceber que ainda tenho um outro ativado.

- Enquanto estou fumando cigarro eletrônico me sinto mais seguro com outras pessoas.

- Eu fumo cigarro eletrônico para me “por pra cima”.

- Quando eu fumo um cigarro eletrônico, parte do prazer é ver o vapor que eu solto.

- Eu desejo um cigarro eletrônico especialmente quando estou confortável e relaxado.

- Eu fumo cigarros eletrônicos quando me sinto triste ou quando quero esquecer minhas obrigações ou preocupações.

- Eu sinto uma vontade enorme de pegar um cigarro eletrônico se fico um tempo sem fumar.

- Eu já me peguei com um cigarro eletrônico na boca sem lembrar de tê-lo colocado lá.

- Eu fumo cigarro eletrônico muito mais quando estou com outras pessoas.

As alternativas e o peso das respostas para cada questão são:

( ) Nunca (1), ( ) Raramente (2), ( ) Às vezes (3), ( ) Frequentemente (4), ( ) Sempre (5).

Source: Author, 2022.

English Translation

- I smoke cigarettes to keep alert.

- Handling a cigarette is art of the enjoyment of smoking it.

- Smoking cigarettes is pleasant and relaxing.

- I light up a cigarette when I feel angry about something.

- When I run out of cigarettes, I find it almost unbearable until I can get another one.

- I smoke cigarettes automatically without even being aware of it.

- It’s easier to talk and engage with other people when I am smoking a cigarette.

- I smoke to get some stimulus, to perk myself up.

- Part of the pleasure of smoking a cigarette comes from the steps I take to light it.

- I find cigarettes pleasurable.

- When I feel uncomfortable or upset about something, I light up a cigarette

- When I am not smoking a cigarette, I am very aware of that fact.

- I light up a cigarette without realizing there is still one burning in the ashtray.

- I feel more confident around people when I am smoking.

- I smoke cigarettes to “perk up”.

- When I smoke a cigarette, part of the enjoyment comes from watching the smoke as I exhale.

- I desire a cigarette especially when I am comfortable and relaxed.

- I smoke a cigarette when I am sad or when I want to forget my obligations and worries.

- I get a huge craving for a cigarette when I haven’t smoked in a while.

- I have found myself with a cigarette in my mouth without remembering putting it there.

- I smoke much more when around other people The alternatives and their respective weight are:

( ) Never [1] ( ) Rarely [2] ( ) Sometimes [3] ( ) Often [4] ( ) Always [5]

Source: Author, 2022.

Translation: Marina Mentor Santos

ATTACHMENT C – Motivational Domains chart correlated with the Modified Reasons for Smoking Scale translated into Brazilian Portuguese adapted for electronic cigarettes

Source: SOUZA, et al., (2009b).

English Translation:

Source: SOUZA, et al., (2009b).

Translation: Marina Mentor Santos