NOVOS HORIZONTES NO TRATAMENTO DO TRANSTORNO DO ESPECTRO AUTISTA – TEA: UMA REVISÃO DOS PRINCIPAIS MEDICAMENTOS E SEUS IMPACTOS

REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10034661

Tiago Negrão de Andrade1

Jaciara Inácio de Almeida2

Wesley Almeida Lima3

Bruna Fernanda Damasceno Ramirez4

Guilherme Rossini5

Adriano Gonçalves Caceres6

Luciane Maria Rodrigues7

Paloma de Lucena Lima8

Abstract:

Context: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) showcases a variety of symptoms and comorbidities, and consequently, a range of pharmacological treatments is made available to address these needs. The diverse medications and approaches suggest a need for individualized treatment and a multidisciplinary approach.

Gap: The wide range of medications highlights a gap in understanding the long-term effects of each treatment and their potential interactions. Moreover, integrating medication with specific public policies for ASD remains a challenge in many healthcare systems.

Purpose: The focus of this study is to analyze and discuss the main therapeutic groups and medications prescribed for ASD, highlighting the role of pharmacists in the implementation of a multidisciplinary therapeutic plan and emphasizing the importance of public policies in this context.

Methodology: An observational design was used, with the analysis of articles from the Web of Science. Therapeutic groups and medications for ASD were cataloged, along with their respective indications.

Results: Various therapeutic groups were identified, including: Atypical antipsychotics (mainly used for hyperactivity, aggression, and repetitive behaviors), Antidepressants (focusing on ritualistic and stereotypical behaviors), Antiepileptics (addressing irritability, aggression, and repetitive behaviors), Glutamate receptor antagonists and Cholinesterase inhibitors (focused on hyperactivity and irritability), among others. Each group presented specific medications that address various ASD symptoms.

Conclusions: The research emphasizes the need for an individualized approach to ASD, considering the wide range of medications and indications. The active role of pharmacists is crucial for implementing effective treatment, and public policies should be shaped by these insights to ensure proper care for individuals with ASD.

Keywords: Autistic disorder. Psychotropic drugs. Psychopharmacology. Pharmacotherapy. Pharmaceutical care.

Resumo:

Contexto: O Transtorno do Espectro Autista (TEA) apresenta uma diversidade de sintomas e comorbidades, e, consequentemente, uma variedade de tratamentos farmacológicos é disponibilizada para atender a essas necessidades. A diversidade de medicamentos e abordagens sugere uma necessidade de tratamento individualizado e uma abordagem multidisciplinar.

Lacuna: A vasta gama de medicamentos evidencia uma lacuna no entendimento dos efeitos a longo prazo de cada tratamento e suas potenciais interações. Além disso, a integração de medicação com políticas públicas específicas para o TEA ainda é um desafio em muitos sistemas de saúde.

Objetivo: O foco deste estudo é analisar e discutir os principais grupos terapêuticos e medicamentos indicados para o TEA, destacando o papel dos farmacêuticos na implementação de um plano terapêutico multidisciplinar e ressaltando a importância das políticas públicas neste contexto.

Metodologia: Utilizou-se um design observacional, com análise de artigos da Web of Science. Os grupos terapêuticos e medicamentos para o TEA foram catalogados, juntamente com suas respectivas indicações.

Resultados: Foram identificados diversos grupos terapêuticos, entre eles: Antipsicóticos atípicos (usados principalmente para hiperatividade, agressividade e comportamentos repetitivos), Antidepressivos (enfocando comportamentos ritualísticos e estereotipados), Antiepilépticos (tratando irritabilidade, agressividade e comportamentos repetitivos), Antagonistas do receptor de glutamato e Inibidores de colinesterase (focados em hiperatividade e irritabilidade), entre outros. Cada grupo apresentou medicamentos específicos que atendem a sintomas variados do TEA.

Conclusões: A pesquisa destaca a necessidade de uma abordagem individualizada para o TEA, considerando a ampla variedade de medicamentos e indicações. O papel ativo dos farmacêuticos é crucial para a implementação de um tratamento eficaz, e políticas públicas devem ser moldadas por esses insights para garantir um atendimento adequado aos indivíduos com TEA.

Palavras-chave: Transtorno do Espectro Autista; Farmacoterapia; Farmacêuticos; Políticas Públicas; Tratamento Individualizado.

Introduction:

ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) is a neurological developmental disorder that begins before the age of three and is also categorized as a behavioral syndrome leading to a wide range of clinical symptoms (GILLBERG, 2000; KLIN, 2006; WHO, 2019).

Autism is not just a disorder but a group of conditions characterized by deficits in communication, social interaction, and repetitive behavior patterns. It is not classified as an intellectual disability because not every individual with autism experiences learning impairments. Its occurrence is between the ages of 2 and 12, with the primary characteristic being extreme difficulty in relating to others (FERREIRA, 2008; LACIVITA, 2017).

Individuals with autism typically have a normal physical appearance and good memory, but their social interactions are impaired. They often isolate themselves from others and find it challenging to maintain eye contact. Their language development may be limited, often relying on gestures for communication (CARVALHO, 2002).

Regarding its etiology, although not yet well-defined, it includes genetic factors, toxins, environmental stressors, altered immune responses, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation (LACIVITA, 2017).

Research suggests that the cause may be related to neuronal changes that occur during the first and second trimesters of prenatal life. It can also be purely genetic or related to environmental factors like prenatal exposure to toxins, viruses, chemical pollutants, or drugs. There are reports linking it with other conditions such as epilepsy, seizures, maternal rubella, phenylketonuria, meningitis, and sclerosis, but there is no concrete evidence (CAVALHEIRA, 2004; FERREIRA, 2008; LACIVITA, 2017).

Available treatment for ASD involves patient monitoring by a multidisciplinary team aimed at fostering their social development, in addition to some psychotropic drugs used to alleviate behavioral and psychiatric symptoms (LACIVITA, 2017).

This article aims to provide a bibliographic review of the pharmacological treatment of ASD in Brazil and how pharmacy services available to healthcare professionals, patients, and families can assist in ASD treatment.

Epidemiologia

ASD was once considered rare, but on a global scale, there has been a noticeable increase in prevalence rates over the past decade, from about 4 in every 10,000 children to 1 in every 68 children. In Brazil, it’s estimated that there are 2 million individuals with autism, and the prevalence rate has shifted from 4 cases per 1,000 children to approximately 1 case per 160 children (OPAS, 2019).

The disorder affects males four times more often than females and does not differ across races (ABRA, 2007). However, when diagnosed, girls tend to be more severely impacted (BOSA, 2006).

The significant observed increase in prevalence rates is not directly related to new cases but rather improvements in the identification and diagnostic processes (KLIN, 2006; LACIVITA, 2017). This increase has positioned ASD as a public health concern.

Diagnostic:

The diagnosis of ASD is primarily based on behavioral aspects. It is recommended that the diagnosis be made using the criteria set forth in the ICD-10 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMD), which evaluates primarily the lack of social interaction, language, and stereotyped movements (GADIA, 2004; SILVA; MULICK, 2009).

While there are no biological markers yet to assist in diagnosing ASD, tests such as the Fragile X test, electroencephalogram, nuclear magnetic resonance, heel prick test, among others, may be performed to determine the cause of the disorder and detect the presence of other diseases (AMORIM, 2019; WHO, 2019).

The disorder is primarily characterized by deficiencies in personal communication and social interaction. Repetitive behaviors and restricted interests are also taken into account (DSM-5, 1995). Unlike a typical child, an autistic child does not respond to smiling faces, grimaces, and the like. They have attachment and social interaction difficulties. However, over time, social interest may develop (AMORIM, 2019).

The disorder always begins before the age of three; it’s usually noticed by parents between 12 and 18 months due to observed delays in speech development and a lack of interest in social relationships (KLIN, 2006).

The DSM-IV-TR provides a list of 12 signs of ASD. A diagnosis is confirmed when a child exhibits at least six of these signs, with at least two symptoms related to impaired social interaction, one related to communication, and one to repetitive behaviors and restricted interests, as shown in Table 1 (SILVA; MULICK, 2009).

Tabel 1: ASD Symptom List

Qualitative Impairment in Social Interaction: a) Marked impairment in the use of multiple non-verbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction. b) Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level. c) Lack of spontaneous efforts to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people. Qualitative Impairment in Communication: a) Delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gesture or mime). b) In individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation. c) Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language. d) Lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level. Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Patterns of Behavior, Interests, and Activities: a) Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest, abnormal in intensity or focus. b) Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals. c) Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects.

Additionally, below are some diagnostic tools, which include scales, surveys, inventories, and tests that assist in the assessment of autistic individuals (ALMEIDA, 2018).

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) takes into account the impaired social interaction, poor language development, damaged cognitive abilities, and early onset, before the age of 3. It’s a table comprised of 15 elements, and each one has a score, ranging from normal to severe, which is totaled based on the characteristics the patient presents.

The Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) is one of the most used scales, and besides characterizing the presence of autism, it also monitors the efficacy of treatments and disease progression. It has 77 questions present in subscales: speech, language, communication, sociability, sensory sensitivity, cognitive and physical sensitivity, health, and behavior.

The Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) is a questionnaire consisting of 57 questions that evaluate the presence of the autism spectrum disorder in people diagnosed with intellectual disability. This scale is divided into 5 symptom areas – sensory, relationships, use of body and objects, language, and social skills and self-help – and assists in the differential diagnosis of ASD.

The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) is an observation scale to assess the social behaviors and communication of the autistic individual, both for adults and children, preferably with a mental age of 3 years or older. The purpose of ADOS is to use observation to differentiate autism from other disabilities and investigate the individual’s social and language development.

The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) is linked to the criteria of ICD-10 and DSM-V and observes language, sociability, and restricted and stereotyped interests that are of the utmost importance for diagnosis. It’s usually conducted in the presence of parents to gather detailed reports on the individual’s behavior to make a differential diagnosis of ASD.

The Portage Inventory Operationalized, Psychoeducational Profile (PEP-3) consists of 5 domains: socialization, cognition, language, self-care, and motor development. It’s used for ages 0 to 6 and assesses the development age of the autistic child. It’s used to design an individualized education plan according to each individual’s peculiarities.

According to the DSM-V – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder are determined by persistent difficulties in social communication and interaction that remain across different environments and situations. These difficulties may manifest in the following ways:

O Difficulties in social and emotional exchanges/interactions, which may manifest as an abnormal initial social contact and inability to maintain a conversation or share very little of one’s interests, emotions, and affections. Or the inability to initiate a social interaction or respond to the initiatives of others.

Difficulties in non-verbal communication behaviors (such as hand gestures, body language, facial expressions) used in social interactions, which may range from poorly integrating verbal and non-verbal communication to abnormal eye contact and body language, or a complete absence of facial expressions and/or any type of non-verbal communication.

Difficulties in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, which may vary from being unable to adjust behavior to different social situations, difficulties in playing pretend games with others, difficulties in making friends, to a complete lack of interest in peers.

The doctor must specify the current severity of the symptoms above. The severity is based on social communication deficits and the restricted and repetitive behavior patterns.

B. Restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities, which are currently or historically manifested in at least two of the following ways:

Stereotyped or repetitive movements, use of objects, or speech (repetitive and seemingly purposeless gestures or speech, such as lining up toys, spinning objects, echolalic repetitive and meaningless phrases).

Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns of verbal or non-verbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking, greeting rituals, a need to take the same route or eat the same food every day).

Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g., strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests).

Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain or temperature, negative response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

The doctor needs to describe the current severity of the symptoms (mild, moderate, or severe) from the social communication deficits and restricted and repetitive behaviors.

C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but might not fully manifest until social demands surpass their ability to cope; they might also be masked later by learned strategies).

D. The symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below par for the general developmental level.

Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Those who have marked deficits in social communication but whose other symptoms do not meet the criteria for autism spectrum disorder should be evaluated for social (pragmatic) communication disorder (AMA, 2007, p. 57).

The doctor needs to specify whether the symptoms are accompanied or not by intellectual disability, language impairment, with a known medical, genetic, or environmental condition. Note on numbering/coding: use an additional code to identify the associated medical or genetic condition. They are associated with other neurological, mental, or behavioral developmental disorders. Note on coding: use an additional code to identify the associated neurological, mental, or behavioral developmental disorder. They are accompanied by catatonia (refer to the criteria for catatonia associated with another mental disorder). Note on numbering: use the additional code – catatonia associated with autism spectrum disorder to indicate the presence of catatonia as comorbidity.

The earlier the diagnosis of ASD is made, the sooner treatments and stimuli will begin, thus increasing the probability of achieving more positive outcomes in the individual’s brain development (ARAÚJO, 2019).

Pharmacological Treatment

When choosing appropriate pharmacotherapy for children with ASD, it’s vital to have a reliable diagnosis based on a thorough and careful assessment, also considering clinical and physical examinations. The choice of medication takes into account the diagnosis, symptoms, history of other pharmacological treatments, and the presence of any other problems or disorders. The aim is to use drugs with fewer side effects, which don’t negatively interfere with the patient’s quality of life, promoting good adherence to the treatment (CORDIOLI, 2014; LEITE; MEIRELLES; MILHOMEM, 2015).

The primary focus of treatment is to improve social interaction and speech. Language is a major concern for parents because it can regress over time. There’s no cure for autism. Pharmacological treatment helps in managing behavioral and psychiatric disorders. Benefits have been reported with atypical antipsychotics for aggression and tantrums; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to alleviate anxiety and repetitive behaviors; and psychostimulants for hyperactivity reports (LEITE; MEIRELLES; MILHOMEM, 2015; LACIVITA, 2017).

Atypical antipsychotics (AAPs), also known as second-generation antipsychotics, work by blocking dopamine and serotonin receptors (LEMKE; WILLIAMS; FOYE, 2008). Their inclusion in treatment should consider specific symptoms like aggression, self-injury, or anger outbursts. Generally, they are safer, more effective, and have a reduced risk of causing short-term side effects like Parkinson’s (NIKOLOV; JONKER; SCAHILL, 2006).

Off-label use of drugs in ASD, as in other patient groups, involves using pharmaceuticals whose indications, administration methods, and dosages still lack regulatory authority approval (SILVEIRA et al., 2013). In Brazil, only risperidone and periciazina are approved by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) for ASD symptoms control (BRASIL, 2012b; BRASIL, 2014).

However, as per a comprehensive review by Eissa et al. (2018), various drug classes have been used in clinical practice for ASD symptoms management. These include atypical antipsychotics for hyperactivity, irritability, aggressiveness, or self-injurious behavior; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for repetitive behaviors and anxiety; opioid antagonists and psychostimulants for hyperactivity; and central nervous system mediators (melatonin) for sleep disorders (NASH; CARTER, 2016).

The variety of drugs used for ASD is because there are various potential pharmacological targets to manage the clinical picture (KUMAR et al., 2012). Additionally, many neurobiological abnormalities exist in a significant part of these individuals, suggesting a potential relationship between these central nervous system changes and the behavioral disorders characterizing the disease (SCHWARTZMAN, 2015). Such changes include neuronal function loss and behavioral and sensory alterations, hyperactivity, aggressiveness, mood fluctuations, and social deficits. Therefore, brain tissue plasticity, cells of the central nervous system, the imbalanced production of certain neurotransmitters, environmental factors, associated comorbidities such as mitochondrial dysfunction, immune problems, oxidative stress, and chronic neuroinflammation are involved in the progress and etiopathogenesis of individuals with ASD (KUMAR et al., 2012).

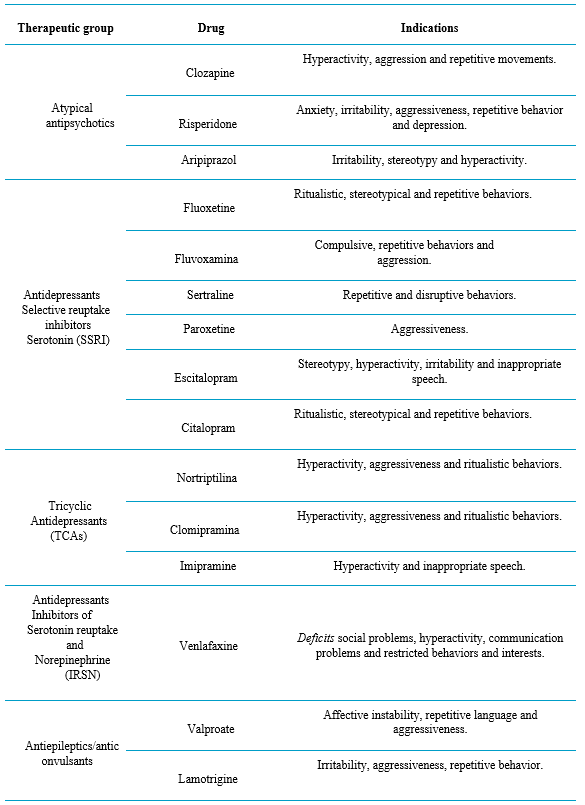

Table2 Main therapeutic groups, drugs and their respective indications in ASD

Source: BARROS NETO; BRUNONI; CYSNEIROS, 2019.

Atypical antipsychotics, or second-generation antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, among others), were developed more recently and are termed “atypical” in reference to their composition and the distinct pharmacological profile from first-generation compounds – typical, conventional ones – having a lower risk of extrapyramidal side effects. These agents possess properties of antagonists for dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors (RANG et al., 2016).

Clozapine was originally intended for the treatment of schizophrenic patients who did not respond to other commonly used antipsychotics in the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia (EISSA et al., 2018; RANG et al., 2016). In ASD, it is adopted to reduce hyperactivity, aggression, and repetitive movements (CHEN, 2001). However, its clinical use is limited due to an increased risk of agranulocytosis, an adverse effect that requires regular blood counts (CHEN, 2001; RANG et al., 2016).

Risperidone is widely used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and, more recently, in ASD (EISSA et al., 2018). Studies have shown its good performance when compared to a placebo in treating anxiety, irritability, aggression, repetitive behavior, and depression (MCDOUGLE et al., 1998; MCCRACKEN et al., 2002). However, its use can lead to weight gain, hypotension, dizziness, and drowsiness (RANG et al., 2016).

Aripiprazole is indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia and Type I bipolar disorder. Due to its unique profile as a partial agonist for D2 and 5HT1A, its use rarely results in adverse effects, such as weight gain (RANG et al., 2016). This is one reason for its recent but significant use in ASD, as it addresses the auxiliary symptoms without leading to this common inconvenience seen with the use of risperidone in ASD (EISSA et al., 2018).

Antidepressants

Antidepressants used in ASD (EISSA et al., 2018) fall under the category of monoamine uptake inhibitors, which further divides into subcategories: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, escitalopram, and citalopram); tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g., nortriptyline, clomipramine, and imipramine); and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (venlafaxine) (RANG et al., 2016).

Among SSRIs, fluoxetine in ASD can result in improved ritualistic, stereotypic, and repetitive behaviors. However, side effects like disinhibition, agitation, hyperactivity, and hypomania are also reported (COOK JR et al., 1992; DELONG et al., 2002; FATEMI et al., 1998; HOLLANDER et al., 2001). With effects similar to fluoxetine in ASD, fluvoxamine reduces compulsive and repetitive behaviors and aggression, though side effects like hyperactivity, aggression, and disinhibition can occur (MARTIN et al., 2003; MCDOUGLE et al., 1996). Similarly, sertraline, escitalopram, and paroxetine in ASD have shown the same potential benefits and side effects (EISSA et al., 2018).

Regarding SNRIs, venlafaxine in ASD has shown promising outcomes for social deficits, hyperactivity, communication problems, and restricted behaviors and interests (EISSA et al., 2018).

As for TCAs in ASD, the use of nortriptyline and clomipramine has been described as beneficial for children diagnosed with this disorder, improving hyperactivity, aggression, and ritualistic behaviors. In contrast, imipramine use isn’t well-tolerated (EISSA et al., 2018). Concerning side effects, a clinical study by Sanchez et al. (1996) showed that clomipramine use resulted in sedation and worsened aggressive behaviors, irritability, and hyperactivity.

Antiepileptics

Antiepileptic drugs, also termed anticonvulsants, are used to treat epilepsy and non-epileptiform seizure disorders (RANG et al., 2016). Partly because of the incidence of seizures in autistic individuals, these drugs have been incorporated into clinical practice (NIKOLOV; JONKER; SCAHILL, 2006).

Valproate operates through various mechanisms, with more studies needed to clarify the significance of each (RANG et al., 2016). Its effects on sodium, calcium channel function inhibition, and potential Gaba action enhancement might be linked to positive outcomes in ASD’s auxiliary symptoms, such as improved affective instability, repetitive language, and aggression (HOLLANDER et al., 2001).

The drug lamotrigine was recently developed, with properties including sodium channel function inhibition and potential calcium channel inhibition (RANG et al., 2016). Although effective for children diagnosed with epilepsy, studies on its use in ASD showed no difference in auxiliary symptom measures compared to a placebo (BELSITO et al., 2001).

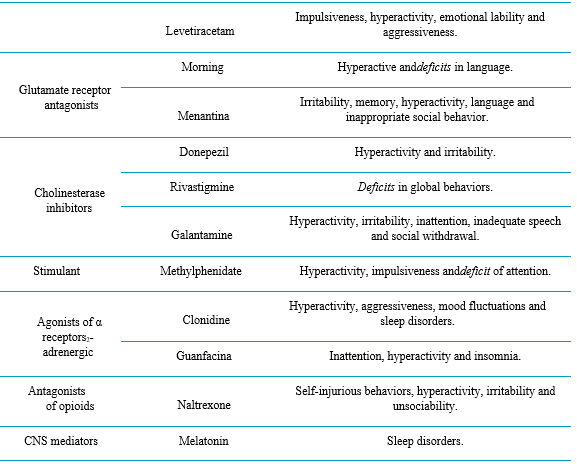

On the other hand, the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam, initially developed as a cognitive-enhancing piracetam analog, had its antiepileptic properties in animal models discovered accidentally (RANG et al., 2016). It exhibited remarkable results in reducing impulsivity, hyperactivity, emotional lability, and aggression (RUGINO; SAMSOCK, 2002).

Glutamate Receptor Antagonists

Memantine, a weak antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (which acts by selectively inhibiting the excessive and pathological activation of this receptor), approved and licensed for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), was originally introduced as an antiviral drug and inhibitor of excitotoxicity (RANG et al., 2016). It has also been used for ASD, following study findings that post-mortem brain samples of individuals diagnosed with ASD had elevated glutamate levels (CHEZ et al., 2007; OWLEY et al., 2006). Similarly, amantadine, initially introduced as an antiviral drug in the late 1960s, but currently used in AD due to its beneficial effects (RANG et al., 2016), has also been employed in the pharmacological treatment of ASD, largely due to its antagonistic action on MNDA receptors (CHEZ et al., 2007; KING et al., 2001; OWLEY et al., 2006). As for study findings, in controlled clinical trials, amantadine showed improvements in hyperactive behavior and language, while memantine resulted in therapeutic advancements related to irritability, memory, hyperactivity, language, and social behavior (OWLEY et al., 2006; CHEZ et al., 2007).

Cholinesterase Inhibitors

It is believed that acetylcholinesterase inhibitor drugs exert their therapeutic action by increasing the concentration of acetylcholine (a substance present at the junction between nervous system cells, responsible for transmitting messages between these cells) when there is reversible inhibition of its breakdown or inactivation by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. Hence, enhancing cholinergic function has contributed to the use of these drugs in the treatment of patients with AD (RANG et al., 2016) and more recently, in ASD, as brain cholinergic neurotransmission dysfunction has also been described in ASD. For this reason, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, newer compounds among cholinesterase inhibitors, have been researched for use in individuals with this diagnosis (KUMAR et al., 2012). In terms of the primary therapeutic effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on ASD, donepezil has proven effective in improving hyperactivity and irritability in children diagnosed with ASD (HARDAN; HANDEN, 2002; HANDEN et al., 2011). Rivastigmine led to a significant improvement in overall behavior, but side effects such as diarrhea, irritability, and hyperactivity were reported (CHEZ et al., 2004; EISSA et al., 2018). Lastly, galantamine resulted in substantial improvements in hyperactivity, irritability, inattention, speech inappropriateness, and social withdrawal (NICOLSON; CRAVEN-THUSS; SMITH, 2006; NIEDERHOFER; STAFFEN; MAIR, 2002). Given the evidence, it seems plausible to support the hypothesis that increasing cholinergic neurotransmission in ASD might lead to assertive therapeutic effects (EISSA et al., 2018).

Stimulants

The primary drug with a predominantly stimulant effect on the central nervous system used in the therapeutic management of ASD is methylphenidate, widely known for its use in treating Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (EISSA et al., 2018). The mechanism of action for methylphenidate (Ritalin) lies in the inhibition of catecholamine uptake, inhibiting the transporters of norepinephrine – noradrenaline (NET), dopamine (DAT), and serotonin (5-HT, Sert) (with lesser potency) and producing a profound and sustained rise of these extracellular neurotransmitters (RANG et al., 2016). Numerous controlled studies show methylphenidate’s ability to attenuate various behavioral aspects of ASD, including hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention deficit (HANDEN; JOHNSON; LUBETSKY, 2000; MARTINO et al., 2004). However, its use also resulted in adverse effects such as insomnia, aggression, and weight loss (JAHROMI et al., 2009; KIM et al., 2017).

α2- Adrenergic Receptor Agonists

The centrally acting antihypertensive drugs clonidine and guanfacine act on noradrenergic transmission in the CNS by selectively inhibiting α2-adrenergic receptors. The primary clinical use of these agents is to reduce blood pressure, as they inhibit the release of norepinephrine and partly through a central action, cause a drop in blood pressure (RANG et al., 2016). However, the administration of these drugs in ASD has shown improvements in hyperactivity, aggression, irritability, and mood instability (EISSA et al., 2018). In addition to treating blood pressure, clonidine is also used to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks; as an adjunctive drug in drug withdrawal; and to reduce menopausal hot flushes (RANG et al., 2016). In ASD, clinical trial results demonstrated potential clinical efficacy and a good safety profile (FANKHAUSER et al., 1992; MING et al., 2008). Guanfacine, a drug with antihypertensive properties and also indicated for ADHD treatment, has shown positive outcomes in studies, including improvements in inattention, hyperactivity, and insomnia. Still, some adverse effects such as fatigue, blurred vision, mood changes, and headache were also reported (BOELLNER et al., 2007).

Opioid Antagonists

Naltrexone is a long-acting opioid antagonist drug commonly used as an adjunct in preventing relapse in detoxified addicts (in the treatment of alcoholism and dependence on exogenously administered opioids) (RANG et al., 2016). It has recently been evaluated in ASD, due to the potential existence of a relationship between alterations in the endogenous opioid system and ASD, specifically concerning the known role of the endogenous opioids β-endorphin and enkephalin in regulating social behavior. The results of these studies indicate significant improvements in the behavioral disturbances characterizing ASD when induced by dysfunction of the opioid system, specifically self-injurious behaviors, hyperactivity, irritability, and unsociability (PANKSEPP; LENSING, 1991; EICHAAR et al., 2006).

Mediadores do SNC

O principal fármaco de interesse dessa categoria no TEA é a melatonina (N-acetil-5-metoxitriptamina) (NASH; CARTER, 2016; CIPOLLA-NETO; AMARAL, 2018). A melatonina é uma substância natural, sintetizada da 5-hidroxitriptamina, sobretudo na glândula pineal, de onde é liberada como hormônio circulante. Sua secreção é controlada pela intensidade da luz, portanto é natural que seja baixa durante o dia e alta à noite. Os impulsos luminosos sobre a retina, por meio do trato retino-hipotalâmico noradrenérgico que culmina no núcleo supraquiasmático (SNC) no hipotálamo, usualmente nomeado “relógio biológico”, produz o ritmo circadiano, controlando a glândula pineal mediante sua inervação simpática (RANG et al., 2016).

O mecanismo de ação desse composto se dá por ação agonista dos receptores MT1 e MT2 no cérebro, portanto possui propriedades antidepressivas, antioxidantes, neuroprotetoras na Doença de Alzheimer e Parkinson e ação indutora do sono. No contexto clínico, é principalmente utilizada para induzir o sono, por ser eficaz no tratamento da insônia, inclusive no autismo (RANG et al., 2016).

Acredita-se que, no TEA, há mau funcionamento da glândula pineal, o que resulta em uma deficiência nos níveis de melatonina. Como a principal função da melatonina é o estabelecimento dos ritmos circadianos, a disfunção na sua síntese, ao resultar em níveis baixos de melatonina, ocasiona distúrbios do sono (SHOMRAT; NESHER, 2019). Desse modo, o uso terapêutico no TEA tem sido investigado em diferentes estudos, com o intuito de avaliar os efeitos da reposição farmacológica de melatonina na melhora da qualidade do sono (ROSSIGNOL; FRYE, 2011).

Canabidiol – CBD

The use of cannabinoids, especially cannabidiol (CBD), has been reviewed by science in the treatment of children with epilepsy that is refractory to conventional treatments. After reports of the use of medicinal cannabis in reducing anxiety, irritability, insomnia, and aggression, parents of children with autism began to see the use of cannabinoids as an alternative to alleviate such symptoms in their children.

According to Poleg et al. (2018), the study of CBD as a suggested candidate for the treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder, CBD does not have a psychotropic effect (it does not cause changes in consciousness and does not provoke perception or mood alterations). The article reviewed pre-clinical and clinical studies looking for findings on the involvement of the endocannabinoid system in neurodevelopment and physical and mental disorders, as well as the safety and efficacy of using CBD in treating the most common behaviors and comorbidities of those with ASD. The study concluded that social interaction deficits are one of the main phenotypes of ASD, and that CBD has shown some pro-social properties in pre-clinical studies.

Aran et al. (2021) conducted a study on cannabinoid treatment for autism in a randomized proof-of-concept trial, analyzing the anecdotal accumulation of evidence of efficacy in humans led to a double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of two oral cannabinoid solutions in 150 participants (aged 5 to 21) with ASD. They found that BOL-DP-O-01-W and BOL-DP-O-01, administered for 3 months, are well tolerated.

For Ponton et al. (2020), a case report provides evidence that a smaller dose than previously reported of a phytocannabinoid in the form of a cannabidiol extract may be able to assist in behavioral symptoms related to autism spectrum disorder, basic social communication skills, and comorbid anxiety, sleep difficulties, and weight control. Further research is needed to elucidate the clinical role and the underlying biological mechanisms of action of the cannabidiol-based extract in patients with autism spectrum disorder.

Public Policies:

In Brazil, there are approximately 2 million people with ASD. Moreover, the disorder also affects those with whom the carriers coexist, affecting the family environment in mental, socioeconomic, and social issues. Therefore, it is necessary to establish public policies that guarantee rights and protection to these individuals, as well as the people they interact with (CAVALCANTE, 2002; OLIVEIRA, 2017).

Article 3 of Law No. 12,764 (Law No. 12,764, § 2; BRAZIL, 2012) establishes the rights of autistic people to have a dignified life; safety; access to health services; physical and moral integrity; the right to education in regular or special education institutions; housing; the job market; social security and assistance; and adequate transportation for effective access to education and health. However, there are still gaps in this law, especially regarding two factors: i) there is no obligation for the presence of guardians for specialized care for autistic students; access for children to daycare and ii) definition of an appropriate and specialized place for autism treatment, which today is carried out at the Psychosocial Care Centers – CAPS, which is a place for the treatment of drug addicts and people with mental illnesses, which is not the case for autistic patients (BRAZIL, 2012; COSTA; FERNANDES, 2018).

In April 2013 (on World Autism Awareness Day, April 2), autistic individuals were included in the actions of the National Program for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – Plan to Live Without Limits, thus ensuring access to guidance on care, services, and provisions related to health by the Unified Health System – SUS (BRAZIL, 2011; BRAZIL, 2018; COSTA; FERNANDES, 2018). And, in 2015, another record was published including ASD as a mental disorder and adding autistic patients to care in psychosocial care networks such as the Child and Adolescent Psychosocial Care Center (CAPSi), the “Care Line for the Attention to People with Autism Spectrum Disorders and their Families in the Psychosocial Care Network of the Unified Health System” (BRAZIL, 2015). Analyzing the context, there is a noticeable need to review existing laws so that they are compatible with the reality of patients and promote the inclusion of autistics in society (COSTA; FERNANDES, 2018).

Final Considerations:

Given the rise in prevalence rates, there is an essential need to expand knowledge about the disorder, its diagnosis, and treatment. An early diagnosis is imperative, based on a methodology that assesses a level to determine the complex treatment. As the literature demonstrates, the use of neuroleptics, specifically aripiprazole and risperidone, is prevalent. There is always a need to control side effects under the guidance of a specialist doctor (ALMEIDA; et al., 2019).

The initial contact may take place at community pharmacies. Hence, the pharmacist can identify signs and suggest a medical consultation for a diagnosis (KHANNA; JARIWALA, 2012; ALMEIDA; et al., 2019). Once the diagnosis is made, the pharmacist can provide pharmaceutical care through a multidisciplinary therapeutic plan. Its aim is to identify, solve, and prevent any medication-related problems (OLIVEIRA; et al., 2015). Within the Unified Health System (SUS), the pharmacist can promote educational actions and guidance about autism to disseminate knowledge, raise awareness among the population, and combat existing prejudices in society. Regarding pharmacotherapy, the pharmacist can contribute by developing a regimen so that each individual receives treatment tailored to their needs. In turn, this minimizes the risks of adverse effects that can impact the daily life of the autistic patient and their family (BRASIL, 2015; LULECI et. al., 2016; ALMEIDA; et al., 2019).

In conclusion, this article gathered references from research on the Medication Control of patients with ASD. It is clear that the pharmacist plays a crucial role in treating autistic individuals. They develop a therapeutic plan, provide continuous monitoring, guide regarding dosage, interactions with other medications or foods, adverse and side effects. Moreover, they promote educational actions to inform both the patient and their family about the disorder and its treatment.

Referências:

ABRA – ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASILEIRA DE AUTISMO. Disponível em www.autismo.org.br/. Acesso em maio de 2021.

ALMEIDA, Hércules Heliezio Pereira; LIMA, Joelson Pinheiro de; BARROS, Karla Bruna Nogueira Torres. Cuidado Farmacêutico às Crianças Com Transtorno do Espectro Autista (Tea): Contribuições e Desafios. Eedic: Encontro de Extensão, Docência e Iniciação Científica, Quixadá, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-7, 2018.

ALMEIDA, Marina da Silveira Rodrigues. Principais Instrumentos Diagnósticos Para Avaliar Crianças com Autismo – TEA. São Paulo. 16 de outubro de 2018. Disponível em https://institutoinclusaobrasil.com.br/instrumentos-diagnosticospara-avaliar-o-autismo-tea/. Acesso em: 09 de outubro de 2019.

AMORIM, Letícia Calmon Drummond. Diagnóstico e características clínicas. AMA – Associação de Amigos do Autista. Disponível em https://www.ama.org.br/site/autismo/diagnostico/. Acesso em: setembro de 2019.

APA – ASSOCIAÇÃO AMERICANA DE PSIQUIATRIA. DSM V – Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais. 5. ed.rev. – Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2014.

APPIO, Eduardo. Discricionariedade Política do Poder Judiciário. 1. ed. Curitiba: Jeruá, 2005. 176 p.

ARAN, Adi et al. Cannabinoid treatment for autism: a proof-of-concept randomized trial. Molecular autism, v. 12, n. 1, p. 1-11, 2021.

ARAÚJO, Liubiana Arantes de. A importância do diagnóstico precoce. Revista Autismo. São Paulo, v. 4, março de 2019.

BARROS NETO, Sebastião Gonçalves de; BRUNONI, Decio; CYSNEIROS, Roberta Monterazzo. Abordagem psicofarmacológica no transtorno do espectro autista: uma revisão narrativa. Cad. Pós-Grad. Distúrb. Desenvolv., São Paulo , v. 19, n. 2, p. 38-60, dez. 2019 . Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1519-03072019000200004&lng=pt&nrm=iso>. acessos em 04 maio 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/cadernosdisturbios.v19n2p38-60.

BOSA, Cleonice Alves. Autismo: intervenções psicoeducacionais. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. Porto Alegre, v. 8, maio de 2006.

BOSA, Cleonice Alves; CALLIAS, Maria. Autismo: breve revisão de diferentes abordagens. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica. Porto Alegre, v. 13, n. 1, 2000.

BRASIL, DISTRITO FEDERAL. Lei nº 12.764, de 27 de dezembro de 2012. Institui a política nacional de proteção dos direitos da pessoa com transtorno do espectro autista; e altera o § 3º do art. 98 da lei nº 8.112, de 11 de dezembro de 1990. Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos

BRASIL. Decreto n.º 7.612, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Institui o Plano Nacional dos Direitos da Pessoa com Deficiência – Plano Viver sem Limite. Disponível em http://www.planalto.gov.br/CCIVIL_03/_Ato20112014/2011/Decreto/D7612.htm. Acesso em maio de 2021.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Diretrizes de Atenção à Reabilitação da Pessoa com Transtorno do Espectro Autista (TEA). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2015. 164 p.

BRASIL. Secretaria Nacional dos Direitos da Pessoa com Deficiência. Dia Mundial de Conscientização do Autismo: Governo lança diretrizes previstas no Plano Viver sem Limite. Disponível em http://www.pessoacomdeficiencia. gov.br/app/noticias/dia-mundialde-conscientizacao-do-autismo-governo-lancadiretrizes-previstas-noplano-viver. Acesso em maio de 2021.

CARVALHO, Maria Monteiro de; AVELAR, Telma Costa de. Aquisição de linguagem e autismo: um reflexo no espelho Revista Latinoamericana de Psicopatologia Fundamental. São Paulo, v. 5, n. 3, julho/setembro 2002.

CAVALCANTE, Fátima Gonçalves. Pessoas Muito Especiais: A construção social do portador de deficiência e a reinvenção da família. 2002. 393 f. Tese apresentada como requisito para conclusão do Curso de Doutorado em Saúde Pública – Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro.

CORDIOLI, Aristides Volpato. Psicofármacos: consulta rápida. 4. ed. São Paulo: Artmed, 2011. 841 p. Disponível em https://www.nescon. medicina.ufmg.br/biblioteca/pesquisa/simples/CORDIOLI,%20Aristides%20Volp ato/1010. Acesso em maio de 2021.

COSTA, Marli Marlene Moraes da; FERNANDES, Paula Vanessa. Autismo, cidadania e políticas públicas: as contradições entre a igualdade formal e a igualdade material. Revista do Direito Público, Londrina, v.13, n.2, p.195-229, agosto de 2018.

FERREIRA, Evelise Cristina Vieira. Prevalência de autismo em santa catarina: uma visão epidemiológica contribuindo para a inclusão social. 2008. 102 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Saúde Pública). Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis

FERREIRA, Marlos José Queiroz. Assistência Farmacêutica Pública: uma Revisão de Literatura. 2011. 53 f. Dissertação (Especialista em Gestão de Sistemas e Serviços de Saúde) – Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Recife.

GADIA, Carlos; TUCHMAN, Roberto; ROTTA, Newra. Autismo e doenças invasivas de desenvolvimento. Jornal de Pediatria. Rio de Janeiro, v. 80, n. 2, p. 1-12, 2004.

GILLBERG, C. COLEMAN, M. The Biology of the Autistic Syndromes. 3rd ed. London:Mac Keith Press, distributed by Cambridge University Press, 2000.

KHANNA, Rahul; JARIWALA, Krutika. Awareness and knowledge of autism among pharmacists. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. Mississippi. V.8, p.464-47, 2012.

KLIN, Ami; MERCADANTE, Marcos. Autismo e transtornos invasivos do desenvolvimento. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. São Paulo, v. 28, maio de 2006.

LACIVITA, Enza; PERRONE, Roberto; MARGARI, Lucia; LEOPOLDO, Marcello. Targets for Drug Therapy for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Challenges and Future Directions. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. Itália, v. 6, n. 3, novembro de 2017.

LEITE, Ricardo; MEIRELLES, Lyghia Maria Araújo; MILHOMEM, Deyse Barros. Medicamentos usados no tratamento psicoterapêutico de crianças autistas em Teresina – PI. Boletim Informativo Geum. Piauí, v. 6, n. 3, p. 1-7, julho/setembro 2015.

LEMKE, Thomas; WILLIAMS, David; ROCHE, Vitoria; ZITO, William. Foye’s Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. 6. ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer, 2008.

LULECI, Nimet Emel; HIDIROGLU, Seyhan; KARAVUS, Melda; KARAVUS, Ahmet; SANVER, Furkan Fatih; OZGUR, Fatih; CELIK, Mehmethan; CELIK, Samed Cihad. The pharmacists awareness, knowledge and attitude about childhood autism in Istanbul. International Journal Clinical Pharmacy Istanbul. v.2, n.10. 2016.

NIKOLOV, Roumen; JONKER, Jacob; SCAHILL, Lawrence. Autismo: tratamentos psicofarmacológicos e áreas de interesse para desenvolvimentos futuros. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr., São Paulo , v. 28, supl. 1, p. s39-s46, May 2006 . Available from <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-44462006000500006&lng=en&nrm=iso>. access on 04 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462006000500006.

OLIVEIRA, Bruno Diniz Castro de; FELDMAN, Clara; COUTO, Maria Cristina Ventura; LIMA, Rossano Cabral. Políticas para o autismo no Brasil: entre a atenção psicossocial e a reabilitação. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva. Rio de Janeiro, v. 27, n. 3, p. 707-726, 2017.

OPAS – ORGANIZAÇÃO PAN-AMERICANA DA SAÚDE. Folha informativa –

ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DA SAÚDE. Perspectivas Políticas sobre Medicamentos da OMS – 4. Seleção de Medicamentos Essenciais. Genebra, 2002.

ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DE SAÚDE – OMS. Classificação Estatística Internacional de Doenças e Problemas Relacionados à Saúde: CID-10. 10ª revisão. São Paulo: OMS; 2000.

PEETERS, Theo. Autismo: Entendimento Teórico E Intervenção Educacional. Rio de Janeiro: Cultura Médica, 1998. 154 p.

PONTON, Juliana Andrea et al. A pediatric patient with autism spectrum disorder and epilepsy using cannabinoid extracts as complementary therapy: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports, v. 14, n. 1, p. 1-7, 2020.

S ONAIVI, E. et al. Consequences of cannabinoid and monoaminergic system disruption in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorders. Current neuropharmacology, v. 9, n. 1, p. 209-214, 2011.

SILVA, Daiana Guarda da; PERAZONI, Vaneza Cauduro. Autismo: um mundo a ser descoberto. EFDeportes.com, Revista Digital. Buenos Aires, n. 171, agosto de 2012.

SILVA, Emília Vitória da Silva; NAVES, Janeth de Oliveira Silva; VIDAL, Júlia. O papel do farmacêutico comunitário no aconselhamento ao paciente. Boletim Farmacoterapêutica. n. 4, Julho/outubro de 2008.

SILVA, Micheline; MULICK, James A. Diagnosticando o Transtorno Autista: Aspectos Fundamentais e Considerações Práticas. Psicologia Ciência e Profissão, vol. 29, n. 1, 2009.

Transtorno do espectro autista. Disponível em https://www.paho.org/bra/index.php?Itemid=1098 Acesso em: novembro de 2019.

WHO – World Health Organization – Disponível em https://www.who.int/en/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders. WILLIAMS, Katrina; BRIGNELL, Amanda; RANDALL, Melinda; SILOVE, Natalie; HAZELL, Philip. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. V. 8, Rev. 2013.

1Mestrando em Ciência dos Alimentos pelo Instituto de Tecnologia de Alimentos – ITAL.

Nutricionista e Farmacêutico pelo Centro Universitário Nossa Senhora do Patrocínio – CEUNSP.

E-mail: tiagonandr@gmail.com

2Farmacêutica pelo Centro Universitário Nossa Senhora do Patrocínio – CEUNSP.

E-mail: jaciaradealmeida@yahoo.com.br

3Farmacêutica pelo Centro Universitário Nossa Senhora do Patrocínio – CEUNSP.

E-mail: wesley.vanessa.lima@gmail.com

4Nutricionista pelo Centro Universitário Nossa Senhora do Patrocínio – CEUNSP.

E-mail: brunaramireznutri@gmail.com

5Doutor em Medicina pela Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo – FMUSP. Graduação em Medicina, pela Universidade Nove de Julho – UNINOVE. Coordenador Acadêmico SOBRAMFA/ SOBRAMFA, Educação Médica & Humanismo

E-mail: guilherme@sobramfa.com.br

6Graduado em Nutrição pelo Centro Universitário Unieuro.

E-mail: sementenative@gmail.com

7Graduada em Administração de Empresas e Ciências Contábeis pela FASP. Graduanda em Nutrição pela Universidade Cruzeiro do Sul

E-mail: encontroessencial@gmail.com

8Nutricionista Graduada no Centro Universitário Nossa Senhora do Patrocínio.

E-mai: limapalomalucena@gmail.com