REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8353199

Marcos Miranda Rodrigues1

Josivane Quaresma Trindade1

Marcos Jessé Abrahão Silva2*

Karla Valéria Batista Lima2

Luana Nepomuceno Gondim Costa Lima1,2

Abstract

The repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt in the care chain, encompassing the various clinical/hospital structures with their multiple health professionals. The nurse, as a member of this team, works directly with patients affected by COVID-19, being exposed to several situations that lead to stress and emotional shock, in addition to leaving them more exposed to serious occupational risks linked to their professional activity. The purpose of this work was to highlight the risks that nurses who provide care to patients affected by COVID-19 are exposed to. This is a systematic review carried out in 3 databases (PUBMED, SCIELO, BVS) between 2020 and 2021. This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023424251). The PEO strategy was used, related to the anagram: population; exposure of interest; and outcome, and the PRISMA Flowchart for better visualization of the results. A total of 16 articles were selected from 6 countries that highlighted that the COVID-19 pandemic had serious repercussions for nurses. Anxiety, stress, emotional overload, exhaustion, fatigue and burnout were the most common emotional changes associated with symptoms of acute stress (ASD), traumatic stress disorder. In addition, the presence of depressive and psychosomatic symptoms such as headache, insomnia, nausea, palpitations and chest discomfort were evidenced. Along with the lack of protective equipment or its prolonged use and the long journeys and the fear of illness were listed as responsible for the emotional upheavals of nurses.

Keywords: COVID-19; Nurses; Occupational risks; mental health.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had serious global repercussions, either due to its pandemic character with a high number of cases/deaths in a short period and lack of specific treatment, as well as due to the strong global economic imbalance. However, its repercussions were felt fundamentally in the care chain, encompassing the various clinical/hospital structures with their multiple health professionals (DE HUMEREZ; OHL; DA SILVA, 2020). Such professionals work in conditions of tension and fear, as the biological and/or psychosocial risks derived from professional activity can be increased by working hours, lack of adequate protective equipment and possible state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion (VEGA et al., 2021).

Nurses, among all health professionals, play an extraordinary role in the fight against COVID-19, their training is aimed at caring for and saving lives, through intense efforts and risks to their health to the detriment of the other. Having to learn to deal with pain, suffering and death. However, these professionals are more susceptible to contamination by the virus, as they are directly exposed to infected patients (PEREIRA et al., 2020).

The work of nurses who work directly with COVID-19 patients can be loaded with stressful situations when managing the complex process of care. Because the constant use of personal protective equipment, such as masks, glasses, aprons, and gloves linked to long journeys and work overloads, leads to strong physical/emotional wear and tear (DOS SANTOS et al., 2020). In addition, the need for hospital isolation and the fear of getting sick and infecting a family member constituted risks to the mental health of nurses, allowing deep trauma (PAIANO et al., 2020; SAIDEL et al., 2020). Thus, the purpose of this article is to review the literature on the risks that nurses are exposed to when caring for patients affected by COVID-19.

2. Material and Methods

This is a systematic review of the literature with the objective to review the risks that nurses who provide care to patients affected by COVID-19 were exposed to during the pandemic period. The objectives of this study are to contribute to the scientific discussion through the condensation of studies published in the scientific environment and to synthesize relevant evidence that can be used as references for new studies. This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023424251).

Design

The study followed the formation stages: 1- Elaboration of the research question and problem; 2- Stipulation of inclusion and exclusion criteria; 3- Selection of the sample; 4- Analysis of articles; 5- Interpretation, discussion and presentation of the review (ROTHER, 2007).

To elaborate on the research question, the PEO strategy was used, related to the anagram: population; exposure of interest; and outcome, as it generates greater integration of results and resolution of the highlighted problem (SANTOS; PIMENTA; NOBRE, 2007).

In view of this, the following question was raised: What are the risks that nurses are exposed to when caring for patients affected by COVID-19? Patient: Nurses who provide care to patients affected with COVID-19 / Exposure of interest: The risks due to the care of patients with COVID-19 and nurses who took care of patients with COVID-19/ Outcome: identify the main risks in nursing care for patients affected by COVID-19 cited in the literature.

Search strategy

Thus, the research question was asked, through which the keywords were selected: (DeCS): COVID-19, Nurses, Occupational Risks, mental health in conjunction with “AND”. The research took place in the following databases: National institutes of Health (PUBMED), Virtual Health Library (BVS), Google Scholar and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SCIELO).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were defined as articles published between January 2020 and September 2021, with full texts, available on a free access platform in English, Portuguese or Spanish; Observational or randomized field research; cohorts; Articles with quantitative or qualitative primary research.

Exclusion criteria were articles published outside the chosen period, articles that were available only in the abstract, letters to the editor, articles with topics not relevant to the research question; reflective articles; literature reviews; course conclusion work, theses and texts that address other categories.

Data extraction

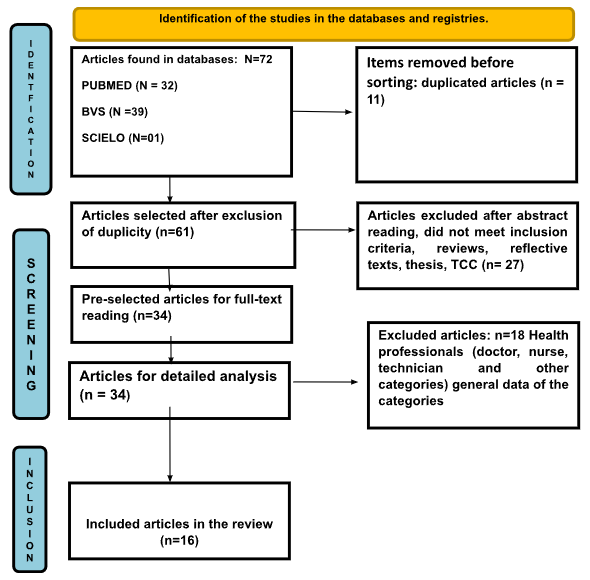

Data were collected in October 2021 and organized and extracted with the help of Microsoft Excel 365. A third researcher (MJAS) resolved discrepancies between the assessments independently by 2 authors (MMR and JQT) in data collection and extraction. The extracted data were displayed in the study in tabular form. The PRISMA flowchart tool, which is part of the PRISMA 2020 protocol, was used to visualize the research in the databases, to show how the final sample was reached, describing all the steps, inclusions, and exclusions (CORDEIRO et al., 2007; LIBERATI et al., 2009; PAGE et al., 2021).

In extracting and visualizing the data, a table was prepared containing the variables: main author, journal, database, country, year of publication, type of study, study population, results, and level of evidence according to the Oxford Center for Evidence-based Medicine, which defines evidence levels 2B as a cohort study, evidence level 4 as case reports; and level of evidence 2C being observation of therapeutic results, ecological studies.

Methodological quality assessment

The quality assessment was carried out based on the types of studies included using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (0–8), JBI Checklist for Cohort Studies (0–11), and JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research (0–10) (AROMATARIS; MUNN, 2017). Only when the conditioned response was “Yes” were the scores for completing the checklist questions taken into account (MUNN et al., 2019).

Studies were rated as having strong evidence when none of the individual components were weak; if the papers received one or more “weak” ratings in the component evaluation, the level of evidence is lowered to middling or weak in the overall evaluation. A third researcher (MJAS) resolved methodological questions and discrepancies between evaluations of 2 authors (MMR and JQT). Furthermore, no statistical analyses were carried out.

3. Results

Literature search

The initial search for articles for systematic review found 72 articles, however, with the selection of materials, 11 were excluded, due to duplicity, 27 articles were excluded after reading the abstract and identification of exclusion criteria and after reading the full texts 18 articles were excluded for not meeting the criteria: not being an article; not be research; did not belong to the theme and did not answer the guiding question adopted (Figure 1), therefore, the final sample consisted of 16 articles. Sampling surveys were international with a higher frequency of Chinese. The total sample of the studies was 7645 nurses. The predominant database was PUBMED.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the article selection process, identification, and eligibility for analysis, Belém, PA, Brazil (2021).

Characteristics of the included articles

Regarding the characterization of the articles included in the final sample of the systematic review, the year of publication of the studies was 2020; China was the most predominant country in the development of studies on the subject with 9 articles, followed by Spain with 02, Jordan 01, Iran 01, Italy 01, Istanbul 01, Egypt 01. As for the language of the publications, all were in English (100%). Regarding the research design of the studies and level of evidence, according to the Oxford classification, cross-sectional studies were obtained – level of evidence 2C (93.75%); cohort study – level of evidence 2B (6.25%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Synthesis of the studies that constituted the final sample of the review, distributed according

Reference/ journal/ Database/ Study location Kind of study Study population Results JBI

scoreEvidence level. ***HUH (SHAHROUR; DARDAS, 2020)/ Nurse Manag, / PubMed/ Jordan Descriptive and comparative quantitative using an online program – Qualtrics 448 64% nurses had acute stress disorder – AED, and 41% had a high rate of psychological distress. (10/10) 2C (LI et al., 2020)/ Medicine/ PubMed / China Cross-sectional study with /convenience sampling 176 77.3% of them had symptoms of anxiety; Anxiety scores in women were significantly higher than in men (P < 0.05); Older nurses had higher levels of anxiety; (P < 0.05). Married nurses had higher levels of anxiety (P < 0.05). The more clinical time spent fighting COVID-19, the higher the level of anxiety (P < 0.05) (7/8) 2C (HOSEINABADI et al., 2020)/ Investigation and Education in Nursing / PubMed /Iran Cross-sectional comparative study between two groups of frontline nurses and those not on the frontline of COVID-19. 245 Work stress and burnout scores in the group exposed to infection were higher than in the group without exposure (p=0.006 and p=0.002) Work stress (p=0.031, β=0.308) was considered a single factor that has a significant relationship with COVID-19-related exhaustion. (8/8)

2C(MURAT; KÖSE; SAVAŞER, 2021)/ Journal of Mental Health Nursing/ PubMed/ Istanbul Cross-sectional and descriptive study 705 56.9% of nurses considered that the isolation care adopted was sufficient, but 63.8% reported difficulty in finding personal protective equipment. 60.9% considered themselves competent in-patient care during the pandemic. 86.2% were afraid of getting infected and/or other people; 58.4% were tested for COVID-19 and 86.7% were negative; 83.1% stated that one of their colleagues had tested positive for COVID- 19. (8/8) 2C (SOTO-RUBIO; GIMÉNEZ-ESPERT; PRADO-GASCÓ, 2020)/ International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health /PubMed / Spain Cross-sectional study 125 It observed that psychosocial risks and emotional intelligence predict 50% of the variance in burnout, 41% of the variance observed in job satisfaction and 32% of the variance observed in psychosomatic health problems in nurses. (6/8) 2C (WANG et al., 2020)/ Medicine/ PubMed/

ChinaCross-sectional and correlational study. 202 The incidence of PTSD in nurses exposed to COVID-19 was 16.83%, the PCL-C score was 27.00 (21.00-34.00) and the highest score in the three dimensions was the dimension avoidance 9.50 (7.00–13.25); (8/8) 2C (LI; ZHOU; XU, 2021)/ Nursing Management/ PubMed/ China predictive study 356 The stress level and prevalence of PTSD significantly increased after working in COVID-19 units. Nurses with less than 2 years’ work experience were significantly associated with a high risk of developing PTSD. (7/8) 2C (LENG et al., 2021)/ Nursing Critical Care/ PubMed/ China.

Cross-sectional study exploring perceived stress status and sources of stress when caring for adult patients with COVID-19 in an ICU.

The main sources of stress included working in an isolated environment, concerns about the shortage and use of personal protective equipment, physical and emotional exhaustion, intense workload, fear of being infected, and insufficient work experiences with COVID-19. (7/8) 2C (CAI et al., 2020)/ Journal of Psychiatric Research/ PubMed / China Cohort study among nurses 702 More than a third of nurses suffered from depression, anxiety, and insomnia in addition to significantly higher risks of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress (P < 0.001). (10/11) 2B (VITALE; GALATOLA; MEA, 2021)/ Acta Biomed for Health Professions/ PubMed/ Italy Descriptive observational study with 291 291 The nurse in the northern Italian region had a higher record of anxiety. Affected psychological factors included: the “Pleasure/Interest” dimension which correlated with the “Unsatisfactory sleep/ wake rhythm” (p=0.004), and “Uncontrollable pain and weakness” (p = 0.001). (10/10) 2C (SAID; EL-SHAFEI, 2021)/ Environmental Science and Pollution Research/ PubMed / Egypt. Comparative cross-sectional study. 420 75.2% dos nurses at the ZFH hospital had a high level of stress versus 60.5% at another ZGH hospital. Workload, dealing with death and dying, personal demands and fears, employing strict biosecurity measures and stigma represented the highest priority stressors in the ZFH, while exposure to the risk of infection was the highest priority stressor among the ZGH. (8/8) 2C (PANG et al., 2021)/ International Journal of Mental Health Nursing/ PubMed/ China Cross-sectional study 282 A high percentage of nurses presenting high levels of anxiety or depression (GAD score ≥10) and depression (PHQ-9 score ≥10) in the present study were 47.52% and 56.74%. (8/8) 2C (ZHAN et al., 2020)/ Current Medical Science/ PubMed/ China. Descriptive cross-sectional study 2768

The median fatigue score of first-line nurses in Wuhan was 4. Their median physical and mental fatigue scores were 3 and 1 respectively. 35.06% of nurses (n = 935) of all participants were in the fatigue state. Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that participants in risk groups for anxiety, depression, and perceived stress had higher scores on physical and mental fatigue.(7/8) 2C (DEL POZO-HERCE et al., 2021)/ International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health/ PubMed/ Spain Cross-sectional and descriptive observational study. 605 Risk factors for the mental health of professionals were identified in more than 90% of nurses (p = 0.009), affecting their psychological state with feelings of exhaustion, emotional overload (p = 0.002), (7/8) 2C (YIFAN et al., 2020)/ Journal of Pain and Symptom Management/PubMed/ China. Analysis exploratory through convenience sample 140 The 10 most frequent symptoms were chest discomfort and palpitations (31.4%), dyspnea (30.7%), nausea (21.4%), headache (19.3%), dizziness (17.9%), xerostomia (15.7%), fatigue (15.0%), drowsiness (9.3%), sweating (8.6%) and waist pain (7.1%). (9/11) 2C (MO et al., 2020)/ Nursing Management/PubMed/China. A transversal survey 180 multiple regression analysis showed that working hours per week and anxiety were the main factors affecting nurse stress (9/10) 2C

4. Discussion

This systematic review with 16 studies involving 7645 nurses from 7 countries showed that nursing care for patients with COVID-19 can lead to serious psychological impacts such as emotional changes, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress and burnout. In addition, the lack of personal protective equipment, work schedule and fear as causes of such shocks. Such findings are corroborated by the review carried out by Pappa et al. (2020) with health professionals, which demonstrates the combined prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress in 21.7%, 22.1% and 21.5% respectively (PAPPA et al., 2020).

The survey conducted by Shahrour and Dardas (2020) in Jordan, pointed out that the majority of nurses (64%) were experiencing Acute Stress Disorder-TEA due to the COVID-19 pandemic predisposing the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder. More than a third of nurses (41%) also experience significant psychological distress (SHAHROUR; DARDAS, 2020). Similar data were found in China, in the study by Cai et al. (2020), which highlights that during the period of the outbreak, nurses on the front line showed significantly higher proportions of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia and signs of disorder. post-traumatic stress disorder (P < 0.001) (CAI et al., 2020).

Anxiety was the disorder with the highest incidence in the studies evaluated with 7 articles (43.75%), indicating that the pandemic brings serious psychological problems to nurses, whose internal trauma is an urgent problem to be solved by public entities. A study by Li et al. (2020) pointed out that 136 (77.3%) frontline nurses had anxiety, 44 (25%) had severe anxiety, which is consistent with the study carried out by Pang et al. (2020), where the incidence of anxiety and depression of nurses working against COVID-19 was 47.52% and 56.74% respectively (LI et al., 2020; PANG et al., 2021).

Burnout syndrome was another important occupational risk highlighted by 2 articles (HOSEINABADI et al., 2020; SOTO-RUBIO; GIMÉNEZ-ESPERT; PRADO-GASCÓ, 2020), however, despite not using the expression burnout in their texts, another 14 studies highlight signs and symptoms in their results characteristic of this emotional state. According to Cocchiara et al. (2019), burnout is characterized as professional burnout resulting from chronic work-related stress, with symptoms characterized by emotional exhaustion, lower productivity and less interest in patients (COCCHIARA et al., 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many nursing professionals to work in conditions of exhaustion, whether physical or emotional. The articles by Herce et al. (2020) and Zhan et al, 2020 highlighted that work activity during the pandemic impacted the psychological state of 90% of nursing professionals, whether due to feelings of physical exhaustion, emotional overload, or long daily working hours. and nighttime for work and little time for leisure or physical activities (DEL POZO-HERCE et al., 2021; ZHAN et al., 2020). The articles by Leng et al. (2020) and Vitale et al. (2020) showed that 37.4% of nurses reported a mild, moderate and severe depressive state. In addition, working at a health center directly involved with COVID-19 was found to be a risk factor for depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress. These authors also showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, health professionals experience sudden and continuous psychological distress that is directly linked to PTSD, a persistent mental disorder that arises through significant tragedies, uncertainties and unpredictability (LENG et al., 2021; VITALE; GALATOLA; MEA, 2021).

This overload that the professional nurse has been enduring when dealing with patients affected by COVID-19 is multiplied by other physical stress factors associated with the need for biosecurity, even knowing its importance, many health professionals have faced a situation of emotional exhaustion when wearing the necessary attire for your protection. In the study by Said and El-Shafei (2020), it was highlighted that reduced dexterity due to multiple layers of gloves, impaired visibility by face shields, back pain, heat stress, and fluid loss were perceived as strong stressors (SAID; EL-SHAFEI, 2021).

The study by Yifan et al. (2020) managed to identify that the changes that nurses have been suffering with the pandemic have psychosomatic repercussions, they identified 3 groups of symptoms among professionals from a COVID ICU in Wuhan who had dizziness, drowsiness, dyspnea, headache, nausea, xerostomia, fatigue, discomfort and chest palpitations related to environmental stress and personal disorders (YIFAN et al., 2020). The article by Mo et al. (2020) emphasizes that these professionals need social, family and spiritual support as well as encouraging each other to discuss their feelings in order to expose their bad experiences, avoiding the accumulation of psychosomatic feelings (MO et al., 2020).

The limitations are that the articles found were cross-sectional studies, in other words, they evaluated the occupational risks at the moment, without the longitudinal observation of the subjects, with that it is not possible to point out what the future consequences for the nurses regarding the emotional aspects. In addition, there was a predominance of studies from China, specifically from Wuhan, despite being the epicenter, the repercussions of the pandemic were felt in different regions of the planet and each location dealt with COVID-19 with the resources available, hence the need for other studies with nurses from other regions with the objective of identifying the repercussions in this category.

5. Conclusion

This review was able to show through the analyzed articles that nurses were faced with many professional challenges that required great ability to deal with the unpredictability of the pandemic, such as high volumes of critical patients, expressive number of deaths, limited resources, scarcity of protective equipment or physical/emotional wear and tear when wearing such garments. In addition, it was pointed out how much this category of health professionals is exposed to occupational risks, showing that nurses need to receive greater attention and investments from government entities in order to guarantee better working conditions and especially psychological support for the maintenance of mental health. and your well-being.

References

AROMATARIS, E.; MUNN, Z. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, v. 2017, n. 1, 2017.

CAI, Z. et al. Nurses endured high risks of psychological problems under the epidemic of COVID-19 in a longitudinal study in Wuhan China. Journal of psychiatric research, v. 131, p. 132–137, dez. 2020.

COCCHIARA, R. A. et al. The use of yoga to manage stress and burnout in healthcare workers: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, v. 8, n. 3, p. 284, 2019.

CORDEIRO, A. M. et al. Revisão sistemática: uma revisão narrativa. Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões, v. 34, p. 428–431, dez. 2007.

DE HUMEREZ, D. C.; OHL, R. I. B.; DA SILVA, M. C. N. Saúde mental dos profissionais de enfermagem do Brasil no contexto da pandemia Covid-19: ação do Conselho Federal de Enfermagem. Cogitare enfermagem, v. 25, 2020.

DEL POZO-HERCE, P. et al. Psychological impact on the nursing professionals of the rioja health service (Spain) due to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 18, n. 2, p. 580, 2021.

DOS SANTOS, W. A. et al. O impacto da pandemia da COVID-19 na saúde mental dos profissionais de saúde: revisão integrativa. Research, Society and Development, v. 9, n. 8, p. e190985470–e190985470, 2020.

HOSEINABADI, T. S. et al. Burnout and its influencing factors between frontline nurses and nurses from other wards during the outbreak of Coronavirus Disease-COVID-19-in Iran. Investigacion y educacion en enfermeria, v. 38, n. 2, 2020.

LENG, M. et al. Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19. Nursing in critical care, v. 26, n. 2, p. 94–101, 2021.

LI, R. et al. Anxiety and related factors in frontline clinical nurses fighting COVID-19 in Wuhan. Medicine, v. 99, n. 30, 2020.

LI, X.; ZHOU, Y.; XU, X. Factors associated with the psychological well-being among front-line nurses exposed to COVID-2019 in China: A predictive study. Journal of nursing management, v. 29, n. 2, p. 240–249, mar. 2021.

LIBERATI, A. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ, v. 339, p. b2700, 21 jul. 2009.

MO, Y. et al. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. Journal of Nursing Management, v. 28, n. 5, p. 1002–1009, 1 jul. 2020.

MUNN, Z. et al. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, v. 17, n. 1, p. 36–43, mar. 2019.

MURAT, M.; KÖSE, S.; SAVAŞER, S. Determination of stress, depression and burnout levels of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of mental health nursing, v. 30, n. 2, p. 533–543, abr. 2021.

PAGE, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, v. 372, p. n71, 29 mar. 2021.

PAIANO, M. et al. Saúde mental dos profissionais de saúde na China durante pandemia do novo coronavírus: revisão integrativa. Revista brasileira de enfermagem, v. 73, 2020.

PANG, Y. et al. Predictive factors of anxiety and depression among nurses fighting coronavirus disease 2019 in China. International journal of mental health nursing, v. 30, n. 2, p. 524–532, abr. 2021.

PAPPA, S. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, behavior, and immunity, v. 88, p. 901–907, 2020.

PEREIRA, M. D. et al. Sofrimento emocional dos Enfermeiros no contexto hospitalar frente à pandemia de COVID-19. Research, Society and Development, v. 9, n. 8, p. e67985121–e67985121, 2020.

ROTHER, E. T. Revisão sistemática X revisão narrativa. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem, v. 20, n. 2, p. v–vi, 1 fev. 2007.

SAID, R. M.; EL-SHAFEI, D. A. Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intent to leave: nurses working on front lines during COVID-19 pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, v. 28, n. 7, p. 8791–8801, 1 fev. 2021.

SAIDEL, M. G. B. et al. Intervenções em saúde mental para profissionais de saúde frente a pandemia de Coronavírus [Mental health interventions for health professionals in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic][Intervenciones de salud mental para profesionales de la salud ante la pandemia de Coronavírus]. Revista Enfermagem UERJ, v. 28, p. 49923, 2020.

SANTOS, C. M. DA C.; PIMENTA, C. A. DE M.; NOBRE, M. R. C. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, v. 15, p. 508–511, jun. 2007.

SHAHROUR, G.; DARDAS, L. A. Acute stress disorder, coping self‐efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID‐19. Journal of Nursing Management, v. 28, n. 7, p. 1686–1695, 2020.

SOTO-RUBIO, A.; GIMÉNEZ-ESPERT, M. D. C.; PRADO-GASCÓ, V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 17, n. 21, p. 7998, 2020.

VEGA, E. A. U. et al. Risks of occupational illnesses among health workers providing care to patients with COVID-19: an integrative review. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, v. 29, 2021.

VITALE, E.; GALATOLA, V.; MEA, R. Observational study on the potential psychological factors that affected Italian nurses involved in the COVID-19 health emergency. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, v. 92, n. Suppl 2, 2021.

WANG, Y.-X. et al. Factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder of nurses exposed to coronavirus disease 2019 in China. Medicine, v. 99, n. 26, p. e20965, 26 jun. 2020.

YIFAN, T. et al. Symptom Cluster of ICU Nurses Treating COVID-19 Pneumonia Patients in Wuhan, China. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, v. 60, n. 1, p. e48–e53, 1 jul. 2020.

ZHAN, Y. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors on fatigue of first-line nurses combating with COVID-19 in China: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Current medical science, v. 40, n. 4, p. 625–635, 2020.

1 Graduate Program in Epidemiology and Health Surveillance (PPGEVS), Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), Ananindeua, Pará, Brazil.

2 Bacteriology and Mycology Section (SABMI), Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC), Ananindeua, Pará, Brazil.

*Corresponding author:

Marcos Jessé Abrahão Silva. Bacteriology and Mycology Section (SABMI)

Evandro Chagas Institute (IEC). Rodovia BR-316, Km 07, s/n, Levilândia, Ananindeua, Pará, Brazil. Zip Code: 67030000. E-mail: jesseabrahao10@gmail.com. Tel: +55 (91) 980179