O CONHECIMENTO TEÓRICO DOS ENFERMEIROS DE UNIDADES DE TERAPIA INTENSIVA QUANTO A PARADA CARDIORRESPIRATÓRIA E REANIMAÇÃO CARDIOPULMONAR

REGISTRO DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.7613036

DUTRA da SILVA, M1

MOREIRA, FL2

MAGALHÃES, CR1

GUIMARÃES, EdaC3

PIMENTA, LS1

XAVIER, SO4

CORREIA da SILVA, DD1

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Cardiorespiratory arrest (CRP) has high mortality rates in Brazil. Although we do not have an exact measure of this problem, the data considered is around 200 thousand PCR/year in the country, with an even split between extra and in-hospital environments. CRP can be defined as the sudden cessation of heartbeat and respiratory movements. Therefore, it is important that the nurse is able to identify and attend to an episode of CRP by performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) with skill and efficiency. Methods: Descriptive and prospective study aiming to present the level of information of nurses working in the ICU on the care of PCR in the hospital environment. Being carried out with 27 nurses from general, coronary, surgical and neurotrauma ICUs of a public hospital of high complexity and reference for these specialties, located in the Federal District. Data were collected between June and August 2016, using a validated questionnaire. The results were described as percentages calculated by the Microsoft Excel® 2007 program. Results: The average number of correct answers was 80%. The questions with the maximum score of correct answers were: those related to the most used drugs, their respective routes of administration and the ventilation of the patient without a definitive airway. The question with the lowest success rate was about the conceptual definition of respiratory arrest. Conclusion: Nurses showed good knowledge on the subject, presenting better results with practical approaches and greater difficulty on predominantly theoretical issues.

Descriptors: Nursing; Intensive care unit; Cardiorespiratory arrest; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Introdução: A parada cardiorrespiratória (PCR) apresenta altas taxas de mortalidade no Brasil. Embora não tenhamos uma medida exata desse problema, os dados considerados giram em torno de 200 mil PCR/ano no país, com uma divisão equitativa entre ambientes extra e intra-hospitalares. A PCR pode ser definida como a cessação repentina dos batimentos cardíacos e dos movimentos respiratórios. Portanto, é importante que o enfermeiro seja capaz de identificar e atender um episódio de PCR realizando a ressuscitação cardiopulmonar (RCP) com habilidade e eficiência. Métodos: Estudo descritivo e prospectivo com o objetivo de apresentar o nível de informação dos enfermeiros atuantes em UTI sobre os cuidados com a PCR no ambiente hospitalar. Sendo realizado com 27 enfermeiros das UTIs geral, coronariana, cirúrgica e de neurotrauma de um hospital público de alta complexidade e referência para essas especialidades, localizado no Distrito Federal. Os dados foram coletados entre junho e agosto de 2016, por meio de um questionário validado. Os resultados foram descritos como porcentagens calculadas pelo programa Microsoft Excel® 2007. Resultados: A média de acertos foi de 80%. As questões com pontuação máxima de acertos foram: as relacionadas aos medicamentos mais utilizados, suas respectivas vias de administração e a ventilação do paciente sem via aérea definitiva. A questão com menor taxa de acerto foi sobre a definição conceitual de parada respiratória. Conclusão: Os enfermeiros demonstraram bom conhecimento sobre o assunto, apresentando melhores resultados com abordagens práticas e maior dificuldade em questões predominantemente teóricas.

Descritores: Enfermagem; Unidade de Tratamento Intensivo; Parada cardiorrespiratória; Ressuscitação cardiopulmonar.

INTRODUCTION

The increase in population life expectancy has brought changes in the morbidity profile and the progressive aging of the Brazilian population.This fact, which already occurs in countries known as developed, generates changes in the causes of general mortality, which has already been occurring in Brazil.The growth of the older population significantly increases the number of chronic-degenerative diseases.Thus, it is expected that patient care and disease prevention practices will start to plan interventions in the distribution, occurrence and treatment of diseases (PEREIRA, 1995).

Cardiorespiratory arrest (CRP) has high mortality rates in Brazil.The statistics of this occurrence are tenuous, precisely because it is not considered as “causa mortis”, with the need to search for data through reports in medical records.Fact, which causes an inaccurate measure of the proportion of this problem.Even so, the data considered is around 200 thousand PCR / year in the country, with an even split between extra and in-hospital environment (SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE CARDIOLOGIA, 2013).

In this context, it is extremely important that nurses working in ICUs base their care on technical and scientific knowledge, refined and updated.The harmony between theoretical knowledge and care practice should be the target of an unremitting search by this professional, aiming at the correct conduct of care for critical patients, well defined and of quality, including with regard to the identification of PCR and its care.

Knowing the situation and assessing the quality of health services is always relevant as a way to improve the conditions of assistance and performance of professionals involved in the process of care, prevention and treatment of diseases.Therefore, it is relevant to identify the level of knowledge of ICU nurses in the care of cardiopulmonary arrest (CRP), since verifying the reality of care based on the pillars of concomitant theory and practice is of great value to confer greater benefits from health servicesfor the population.

CRP is considered a complication with a high degree of complexity, especially when present in patients who are in critical condition, such as those admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and can be defined as a sudden and unexpected condition of absolute disability. of tissue oxygen. Which may be due to circulatory inefficiency or cessation of respiratory function (CINTRA; NISHIDE; NUNES, 2005). It can also be defined as the sudden cessation of heartbeat and respiratory movements (KNOBEL, 2006). Thus, following early practices of correct maneuvers in the rapid and efficient implementation of advanced support, the chances of immediate recovery and survival are increased. The American Heart Association (AHA) says that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) aims to restore vital functions for some time, but the serious and irreversible brain damage that occurs due to the delay in care will be determining the future quality of life of the patient individual (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015).

The participation of nurses in the PCR protocol is of fundamental importance, since they act directly in the 24 hours with the patient, identifying situations of clinical worsening requesting the presence of the rest of the multidisciplinary team and initiating cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers.Thus, nurses must be well updated and trained, as they work together with the medical and physiotherapy team, acting in unexpected situations in an objective and synchronous way in which they are inserted (VIEIRA, 1996).

Therefore, the full success of assistance in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit) will depend on the presence of human, financial, material and equipment resources, as well as the clear determination of the roles of each professional involved in the process.It is also emphasized the importance of the professionals’ scientific and technical knowledge and the need for well-defined care protocols, aiming at standardizing the actions to be followed, as a way to facilitate the therapeutic approach.These characteristics as a whole are what will enable an effective service in any situation, including the PCR service (FILGUEIRAS FILHO; FLAG; DEMONDES; OLIVEIRA; LIMA; CRUZ, 2006).

Recently, Moura et al (2019) pointed out deficiencies in the immediate conduct of nurses after the recognition of CRP, in relation to the cardiac rhythms found, including the differentiation between shockable and non-shockable.The low percentage of totally correct answers demonstrated the need to update professionals in order to standardize and improve care, to improve the quality of nursing care.Another study identified important gaps in the nurses’ knowledge regarding the medications used during the care of the PCR and identification of the different rhythms of the event (MOURA ET AL, 2019).

Since PCR is a constant reality in ICUs, care should be optimized and, within therapeutic possibilities, these numbers should be reduced through a team based on well-trained scientific technical knowledge and whose goal is to reduce this.

METHODS

This is a descriptive and prospective study to present the level of information on protocols and activities necessary for the care of PCR in an ICU. The research was carried out in a public hospital, of high complexity and reference for neurosurgery and trauma specialties, located in the Federal District.

The research population consisted of nurses working in any of the four adult ICUs that make up the hospital. Each ICU has a capacity for forty-six beds and are distributed by specialties: trauma ICU, surgical ICU, general ICU and surgical coronary ICU. In total there are forty nurses, who work during the day (morning and afternoon) and at night. Of the aforementioned ICUs, the only one in which nurses are exclusive is the neurotrauma ICU, in which there are an average of three to four nurses per shift, since it is the unit with the most beds, twenty five of which per ward. The other nurses alternate their shifts in the remaining three ICUs: general, surgical and coronary according to the daily scale, with the exception of routine nurses who are fixed each in their respective ICU. Nurses who were away from work activities during the period of data collection, which occurred from June to August 2016, were excluded from the study.

Data collection was carried out by one of the researchers, using a questionnaire containing two parts: The first part, containing eight questions, addressing the characterization of the nurse (identification, professional training, work characterization, participation in basic life saving courses) (BLS), Advanced Life Saving (FAS) and updates on PCR and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and the second part, containing twenty questions, addressing nurses’ knowledge about cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. had been validated by BELLAN in his master’s dissertation, carried out in 2010, at a teaching hospital in São Paulo. The BELLAN questionnaire was adapted according to the International Consensus of Science – Guidelines 2015 for CPR and Emergency (EMG) cardiovascular and also according to the cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cardiovascular care guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology (SBC) of 2013. After this update, the questionnaire was composed only of closed questions, which facilitated its application (BELLAN; MUGLIA ARAÚJO; ARAÚJO, 2010).

The questionnaire was delivered to Nurses individually after signing the free and informed consent form (IC), which were then collected by the research team in an envelope, respecting the subjects’ confidentiality.The study followed all the ethical precepts established in Resolution Nº 466/2012 of the National Health Council/ Ministry of Health, being approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Teaching and Research Foundation (FEPECS) of the State Health Secretariat of the Federal District under the number 52581215.0.0000.5553.The data were entered in a spreadsheet of the Microsoft Excel® 2007 program, and distributed in the form of integers and percentages.After their distributions were analyzed based on references of the theme.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

There are a total of 40 nurses in the ICUs of this institution.Of these, 20% refused to participate, 12.5% were on vacation or leave during the data collection period, resulting in a total of 27 participating nurses.Most were female (74%), a fact that corroborates the perspective of sexual division in the nursing profession.According to research data carried out by FIOCRUZ / COFEN (2015), published on the COREN-DF website, 83.3% of nurses in this district were female, reflecting the feminization of nursing in society.The same study shows that 70.9% of nurses were up to 40 years old at the time of the survey.In our population, 59.3% were aged 20-30 years, 22.2% aged 30-40 years and 18.5% aged ≥ 41 years (3 women and 2 men).The average age was very close among men and women working in the sector, being 35.7 and 33.2 years old, respectively.

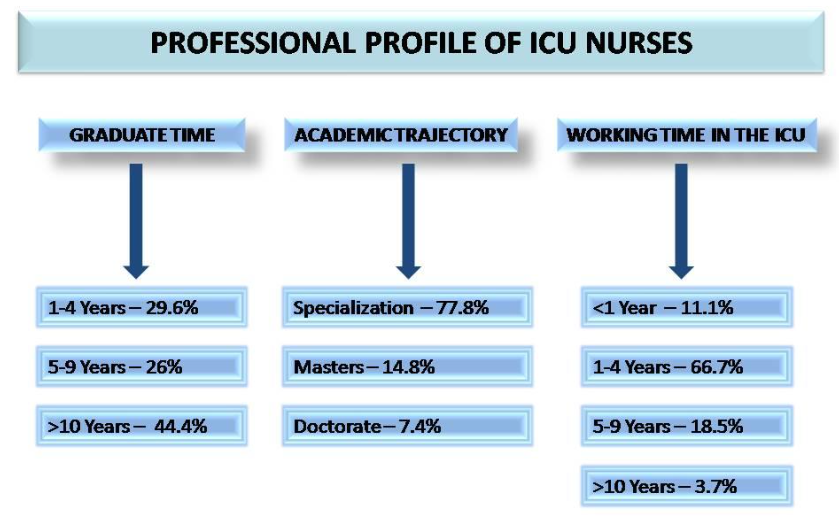

Fig. 1: Professional profile of nurses in the ICU of the study hospital.

As we can see in figure 1, most of the interviewees had more than ten years of training (44.4%).As for graduate courses, 77.8% professionals had specialization and 14.8% had a master’s degree.According to the COFEN survey, 72.9% of nurses in the capital had a postgraduate course.Among the areas of specialization carried out, the most cited in our study were: Intensive Care Unit (66.7%), Urgency and Emergency (29.6%) and Public Health (3.7%).

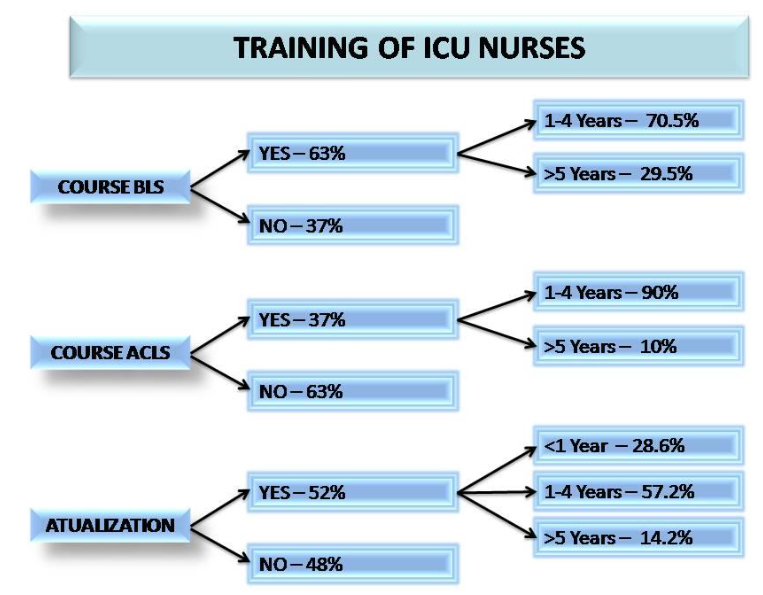

Regarding the participation of nurses in the Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Life Support (LAS) courses, it was found that 63% (13 women and 6 men) participated in the BLS and 37% (8 women and 2 men) of the FVO.The average time they underwent BLS and FAS was between 1 and 4 years for the majority, 70.5% and 90%, respectively (Figure 2).There is a small number of nurses with a course in VAS.

Training and updating are technical forms of capacity building for the necessary care of patients suffering from CPA within an intensive care unit, therefore, they aim to contribute to the dissemination of knowledge associated with a homogeneity of its fundamentals.

Fig. 2: Characteristics of the training carried out by the ICU Nurses at the study hospital.

As for updating the PCR/RCP service, 52% reported having performed some type of activity, both through reading books and periodicals, as well as lectures, courses or classes, and, on average, this update occurred between 1 and 4 years for 57.2% of nurses. COFEN data showed that in 2015 70.1% of nurses working in the Federal District sought professional improvement in the last 12 months prior to the survey.Among the difficulties found for the lack of expansion of professional knowledge, the most cited were respectively: lack of time and encouragement; lack of financial conditions; and, lack of institutional support and encouragement.

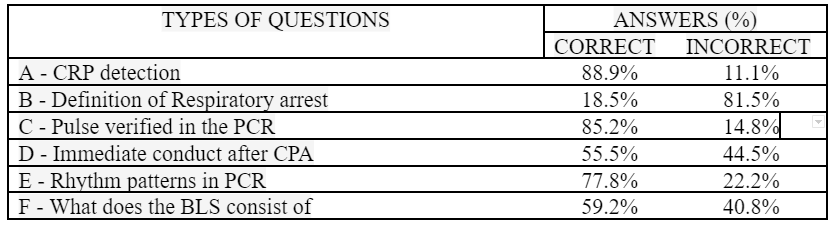

TABLE 1: Distribution of ICU nurses’ answers about theoretical knowledge in PCR/CPR.

CRP = Cardiorespiratory arrest; SAV (Advanced Life Support); BLS (Basic Life Support); CTE (External Chest Compression), CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation), ICUs (Intensive Care Units).

Source: Researchers’ database.Brasilia DF.Brazil. July, 2016.

In the data pointed out in the questions related to topic A – detection of CRP in the Intensive Care Unit in an intubated, sedated (RASS-5) and mechanically ventilated (MV) patient, nurses presented 88.9% of correct answers, showing a good level knowledge in the correct identification of clinical signs of a PCR (Table I). This data differs from a study carried out by Espíndola et al (2017), in which only 33.3% of nurses knew how to correctly recognize CRP, and 66.7% answered partially correct.

The questions that underlie cerebral cardiorespiratory resuscitation must be the domain of nurses, always being able to recognize when the patient is in cardiac arrest or about to present it (ZANINI; NASCIMENTO; BARRA, 2006).

The thematic of question B (topic B) refers to the conceptual definition of respiratory arrest. Nurses indicated only 18.5% of correct answers, representing a low rate, since the researched population works in an intensive care unit dealing directly with critically ill patients. This data is probably due to the fact that they are inattentive to the statement of the issue that dealt only with respiratory arrest and not cardiorespiratory arrest. Respiratory arrest is characterized by apnea or agonized breathing, being defined as the arrest of respiratory movements, with the consequent interruption of the exchange of gasses between air and blood. It determines a critical situation that, if it does not have an immediate treatment, can lead, in a matter of seconds or minutes, to cardiac arrest and even death (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015).

Regarding the pulse to be checked in the PCR (Topic C), 85.2% of nurses marked the correct answer, which is the carotid pulse. However, studies show that both health professionals and lay rescuers find it difficult to detect the pulse, with the former taking a longer time to perform it and, therefore, checking the pulse is not emphasized (GONZALEZ, 2013).

Regarding the immediate actions to be taken after the diagnosis of CRP (topic D), only 55.6% answered correctly. Among the less pointed alternatives, those considered as correct were those that referred to placing the victim in the supine position and removing objects from the oral cavity. A study carried out in 2003, in France, showed that of the nurses and doctors of a university hospital facing a PCR, 50% would open airways, 75% would start ventilation, 86% started external cardiac massage, while 42% would call for help. The absence of a call for help corresponds to a serious error, since this delays the arrival of the defibrillator, which is the only device capable of reversing a PCR by shockable rhythm such as ventricular fibrillation (VF) and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (TVSP) (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015).

In a survey conducted in Brazil, Espíndola et al (2017) addressing the initial conduct of care for PCR, 66.7% of respondents answered partially correct and only 33.3% totally correct. In PCR, four rhythm patterns are found: ventricular fibrillation (VF), pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), pulseless electrical activity (AESP) and asystole. However, the highest survival rates are found when the initial rhythm is ventricular fibrillation (SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE CARDIOLOGIA, 2013). According to a survey by SBC (2019), when defibrillation is performed early, within 3 to 5 minutes of the start of the event, the chances of success are around 50% to 70%. In an in-hospital environment, the most frequent CPA rhythm is Pulseless Electrical Activity (AESP) or asystole, with a worse prognosis and low survival rates, below 17%.

As for the patterns of rhythms that can be found in PCR (topic E), 77.8% of correct answers were obtained. The results obtained contrast with a study carried out in Pernambuco, in 2016, in which only 39.13% of nurses correctly identified all the rhythms found in a PCR (MOURA et al, 2019). Beccaria’s research (2017) also differs from the present study in this aspect, pointing out the CRP rhythm patterns as the main difficulty on the part of the interviewed professionals.

The work environment interferes with the ability to identify rhythm patterns, as it provides less or greater contact with the monitoring of patients, as well as the identification of emergency situations (MEANEY; NADKARNI; KERN; INDIK; HALPERIN; BERG, 2010. De In fact, the population of this study has in their work environment, contact and management with equipment and technologies that allow continuous monitoring, such as defibrillators that allow the professional to read the cardiac rhythm at the time of cardiac complications.

For the sequence recommended in the BLS (topic F), the subjects who answered incorrectly totaled 59.2%, with the rapid recognition of CRP and early defibrillation being the least marked choices among the options considered correct. The score found in this research corroborates a study by Moura et al (2019), which demonstrated that the theoretical knowledge of nurses at a university hospital about BLS is deficient.

There was a lower rate of correct answers, relative to what constitutes basic life support (BLS), where only 59.3% of nurses answered this question correctly. According to AHA (2015), BLS consists of immediate intervention, with the start of cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers, aiming at maintaining ventilation and circulation through the opening of the airways, ventilation, external chest compressions and early defibrillation for cases of VF and pulse-free TV. The success of this procedure depends on the skill and speed with which the maneuvers are applied. This data may justify the difficulty encountered by many nurses regarding assistance to patients with cardiac arrest in the prehospital environment, since it is not an everyday situation in the ICU.

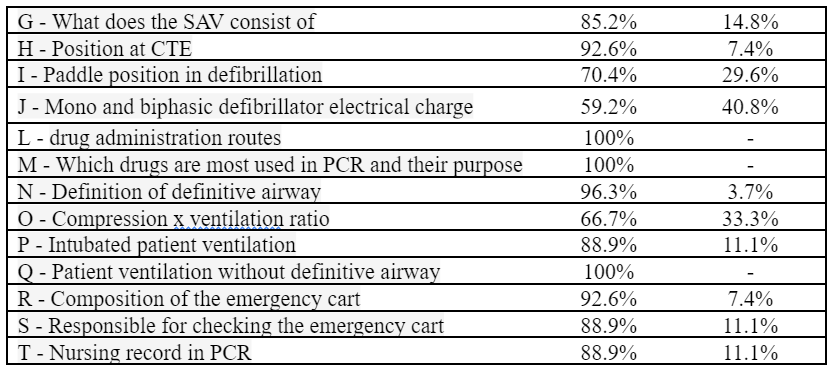

When approached about VAS (topic G), the percentage of correct answers was 85.2%, with maintenance of basic life support, early defibrillation, opening of the airways and artificial ventilation the alternatives considered correct (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015 ). Perhaps the fact that there are more doubts about basic support, compared to VAS, is that the first is usually performed outside the hospital environment. However, in the intensive care unit, nurses are more often faced with advanced support. Even so, it can be said that it is encouraging to identify that 85.18% answered the question about what VAS consists of, presenting a favorable scenario for the study site.

The majority (92.6%) were right about the body posture for performing external chest compression (topic H), which refers to the complete return of the chest to each compression, the use of the hypotonic region of the hands and arms forming a 90º angle with the patient’s chest and perform the compressions ensuring a heart rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015). The data found by Almeida; Araújo and Dalri (2011) in a medical clinic unit of a public hospital in the metropolitan region of Campinas differ, as there were 46.6% correct answers, differently from the research in question. This may have occurred due to the sector difference, since the medical clinic does not deal with the PCR situation as often (BERTOGLIO; AZZOLIN; SOUZA; RABELO, 2008).

About de-positioning for paddle placement in defibrillation (topic I), 70.4% of the subjects in the sample were correct when checking the option right infraclavicular region and cardiac apex (KNOBEL, 2006).

Regarding the electrical charge for defibrillation (Topic J), there was a 59.3% correct answer, the most pointed incorrect option was on the amount of Joules for both single-phase and biphasic defibrillators. This concept of 200 joules was related to the Guideline of 2000, whereas the Guidelines AHA 2015 provides a load of 360 J (for single-phase defibrillators) and 200J (for biphasic) (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015). For the possible routes of drug administration during the PCR (item L), there was a 100% accuracy.

Most nurses (96.3%) agreed on the definition of the definitive airway (topic N), thus being the alternative that said that the tube in the trachea with the inflated cuff was the most marked. This service step refers to the SAV (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015).

When asked about the compression and ventilation ratio (topic O), 66.7% agreed that the ratio of 30 compressions and 2 ventilations should be applied. Of the incorrect answers (33.3%), the most marked was the one with the 15:2 ratio (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015). The 30:2 ratio proposed by AHA 2015 is accepted worldwide as it is the one that best presents scientific confirmation of effectiveness. The old 15:2 ratio fell out of favor, as it required the rescuer to interrupt chest compressions to perform unnecessary ventilations since the blood supply to the heart is reduced during a PCR, so there is no need for large amounts of oxygen (AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION, 2015). This reinforces the need for training and updates.

As for the way to ventilate the intubated patient (topic P), there were 88.9% of correct answers, demonstrating a good knowledge of the item in question. Ventilation without an advanced airway is performed with a manual resuscitator enriched with oxygen (O2) and a face mask, and ideally it should be used in the presence of two rescuers, one responsible for compressions; and another, for applying the ventilations with the device. With one hand, a letter “C” should be made with the thumb and forefinger and positioned above the mask, pressure should be applied against the victim’s face in order to seal it as best as possible and position the other three fingers on the jaw to stabilize it and open the victim’s airway (CUNHA; TONETO; PEREIRA, 2013).

When an advanced airway (endotracheal intubation, combitube, laryngeal mask) is installed, the first rescuer will administer continuous chest compressions, and the second will deliver ventilation with the manual resuscitator enriched with O2 every 6 to 8 seconds, about 8 at 10 breaths per minute, in victims of any age. Compressions should not be paused to apply ventilation in the case of installed advanced airways (CUNHA; TONETO; PEREIRA, 2013).

Regarding the composition of the emergency cart (topic R), 92.6% of nurses answered the question correctly, leaving a 7.4% error rate. The least pointed item was the alternative related to the material for chest compression that concerns the rigid board located on the side of the cart.

In a realistic simulation study, performed in the emergency room, in 2015 by Mayumie; Bittencourt; Coelho (2015) at the Ibirapuera unit of the Albert Einstein hospital, latent flaws in patient safety were detected, among them was the lack of a rigid board in the PCR cart present in the emergency room, forcing the nursing technician to seek this device outside the room emergency, which proves to be an item neglected by the team, but indispensable for performing an effective cardiac compression (MAYUMIE; BITTENCOURT; COELHO, 2015).

The responses referring to the person responsible for checking the cart (Topic S) showed that a large part (88.9%) is aware that the nurse is responsible for this care, and that the nurses who made a mistake believed that all health professionals are responsible for the cart checklist. Some authors report that the systematic verification of the emergency cart is up to the nurse, observing the presence and validity of the listed materials and drugs and the functioning of the cardioverter. This cart must be checked on a pre-set date and after each use and the seal number and the conference date are recorded in a specific form (PONTES; FREIRE; MENDONÇA; SANTANA, 2010).

For the content of the nursing records in the care of PCR (Topic T), there was an 88.9% correct answer by the subjects. Of the nurses who made mistakes, most did not check the item that said it was necessary to register the drugs used and the route, in addition to the number of shocks and the care team. This data differs from the study carried out by Grisante (2013), which had a correct rate of 36.8%. It is worth mentioning that, currently, there are protocols for the registration of CRP and, nationwide, a form was prepared and validated in order to obtain more complete and succinct notes and can accurately describe what happened to the patient at the time of CRP/RCP, also serving as a legal document (PONTES; FREIRE; MENDONÇA; SANTANA, 2010).

As for the factors that interfere with the team’s lack of knowledge, the research participants could check more than one alternative or even all. Therefore, the following factors were statistically verified in decreasing order: Deficit of knowledge, lack of training and courses on the subject were marked by 77.8%. Inexperience, insecurity and lack of skill were marked by 19 participants (70.3%). These data are in line with the study by Silva and Padilha (2001), in their study on iatrogenicity in CPR procedures. In the study, they cited the professional inexperience, lack of attention and technical-scientific ignorance of the team members, in addition to the lack of professional inputs and materials used in the care of critical patients as determining factors for the failure of a resuscitation (SILVA; PADILHA, 2001).

A score of half a point was provided for each question, totaling the sum of ten points for the twenty questions. Overall, the average number of points obtained by nurses was 8 points, with the minimum achieved by nurses being 6.0 points and the maximum being 9.5 points, out of the total of 10 points (20 questions) they could reach.

The study showed that nurses obtained a good average in the questionnaire applied, of 8.0 points (80%), this may have happened because they are professionals who frequently work with this situation of CRP in their sector, and it is known that how much the more frequent the contact with this situation, the greater the learning and development of skills.

This result was similar to that found in a study carried out in a hospital specialized in cardiology in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, which demonstrated that the average number of correct answers by nurses was 7.5, with just over 75% being more than 75 correct % of questions (BRIÃO; SOUZA; CASTRO, 2009). This good performance is due to the higher incidence of PCR in the closed units, which is a facilitator to keep the team more trained, attentive and skilled, allowing a better interaction between the team members.

CONCLUSION

It can be considered that the nurses at the referred unit perform their role effectively and efficiently, with regard to nursing care for patients when they have CRP. It was also observed that these professionals have deficiencies in specific items of theoretical-scientific basis, since the question with the least number of correct answers was about the definition of respiratory arrest. This shows that the practice and direct contact with the situation of CRP is a differential for the nurses’ performance in the scenario in which they find themselves.

These results were presented to the Continuing Education sector of the studied Hospital so that they could act and take the appropriate measures regarding the findings in this study. Periodic updates and training through courses and lectures were suggested.

This research had some limitations, such as the non-participation of all nurses, which ended up not allowing the totality of these professionals to be evaluated. Therefore, we recommend carrying out new studies, especially after intensive training with these teams, aiming at updating and improving care. It is also necessary to seek moments to discuss cases, training and update in service, being a feasible strategy to improve the care indicators in the care of a PCR.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

ALMEIDA AO; ARAÚJO IE; DALRI MC. Theoretical knowledge of nurses about cardiopulmonary arrest and resuscitation in non-hospital units for urgent and emergency care. In: Rev. Lat. Amer. Nurse 2011, p. 8-10.

AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION (AHA) Advanced life support in cardiology. Ed. Dallas, 2015, p.6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 18.

BECCARIA LM; SANTOS KF; TRCOMBETA JC; RODRIGUES AMS; BARBOSA TP; JACON JC. Cuidarte Enfermagem 2017 jan.-jun .; 11 (1): 51-58 Available at: http://www.webfipa.net/facfipa/ner/sumarios/cuidarte/2017v1/7%20Article%20Conhecimento%20Enfermagem%20Parada%20cardiorrespirat%C3%B3ria%20PCR.pdf Accessed on: 08/20/2020.

BELLAN MC, ARAUJO IIM, ARAUJO S. Theoretical training of nurses to attend cardiac arrest. In: Rev. Bras. of Enferm. Brasília- DF, v. 63, n. 6, ten. 2010. Available at: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-71672010000600023> Accessed on 10/31/2016.

BERTOGLIO VM; AZZOLIN K; SOUZA EN; RABELO ER. Time elapsed from training in cardiorespiratory arrest and the impact on nurses’ theoretical knowledge. In: Rev. Gaúcha de Enferm., 2008, p. 454-60.

BRAZIL, FEDERAL NURSING COUNCIL. Research on the profile of nursing professionals in Brazil. Fiocruz, 2015. Available at: <https://www.coren-df.gov.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/perfilenfermagemdf.pdf> Accessed on 08/27/2020.

BRAZILIAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY (SBC). Update of the Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Cardiovascular Emergency Care Directive of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology – 2019. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2019; 113 (3): 449-663. Available at: http://publicacoes.cardiol.br/portal/abc/portugues/2019/v11303/pdf/11303025.pdf Accessed on: 08/28/2020

BRIÃO RC; SOUZA EN; CASTRO RA. Cohort study to evaluate the performance of emergency physicians in hospitals in Salvador / Bahia on the care of victims with CPA. In: Rev. Lat. Amer. de Enferm., 2009, p. 12-14.

CINTRA RA; NISHIDE VM; NUNES WA. Nursing care for critically ill severely ill patients. Ed. Atheneu. São Paulo, 2005. p. 323.

FILGUEIRAS FILHO NM; AC FLAG; DEMONDES T; OLIVEIRA A; LIMA AS; CRUZ V. Evaluation of the general knowledge of emergency physicians at hospitals in salvador regarding the care of victims with cardiorespiratory arrest. In: Rev. Lat. Amer. of Enferm. Bahia-SV, 2006, p. 200.

GONZALEZ MM. I Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology: Executive Summary. In: Arq. Bras. of Cardiol. Rio de Janeiro, v.101, n.2, Suppl. 3, August, 2013, p.105-13.

GRISANTE DL; SILVA ABV; AYOUB AC; BELINELO RGS; ONOFRE PSC; LOPES CT. Evaluation of nursing records on cardiopulmonary resuscitation based on the utstein model. In: Rev. Red. Enf. Nord, 2013, p.1177-84.

KNOBEL, E. Intensive Care: Nursing. Ed. Atheneu. São Paulo, 2006, p 200.

MAYUIMI R; BITTENCOURT T; MM RABBIT. In-situ simulation, a multidisciplinary training methodology to identify opportunities for improving patient safety in a high-risk unit. In: Rev. Bras. from Educ. Physician, 2015, p.286-293.

MEANEY PA; NADKARNI VM; KERN KB; INDIK JH; HALPERIN HR; BERG RA. Rhythms and outcomes of adult in-hospital cardiac arrest. In: Critical Care Med, 2010, p.101-8.

MOURA JG et al. Knowledge and Performance of the Nursing Team of an Emergency Department at the Cardiorespiratory Stop Event. Rev Fund Care Online. 2019. Apr./Jun.; 11 (3): 634-640. DOI: http: // dx.doi.org/10.9789/2175-5361.2019.v11i3.634-640.

PEREIRA MG. Epidemiology Theory and practice. Ed. Guanabara Koogan, 1996.

PONTES VO BRIDGES; FREIRE ILS; MENDONÇA AEO; SANTANA SS. Bibliographic update on protocols for the institution of emergency cars. In: FIEP BULLETIN, 2010. Available at: http://www.fiepbulletin.net/index.php/fiepbulletin/article/viewFile/1676/3265, p. 8-10. Accessed on 11/14/2016.

SILVA SC; PADILHA KG. Cardiorespiratory arrest in the intensive care unit: theoretical considerations on factors related to iatrogenic occurrences. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP, 2001.

SPÍNDOLA MCM; SPÍNDOLA MMM; MOURA LTR; LACERDA LCA. Rev. Enferm. UFPE (online), Recife, 11 (7): 2773-8, jul., 2017. Available at: DOI: 10.5205 / reuol.10939-97553-1-RV.1107201717.

VIEIRA SRR. National Council for Cardiorespiratory Resuscitation. In: Arq. Bras. of Cardiol. 6th Ed., 1996. Available at: <http://www.uniandrade.edu.br/links/menu3/publicacoes/revista_enfermagem/oitavo_amanha/artigo15.pdf> Accessed on 10/15/2015.

WEDGE C; TONETO M; PEREIRA E. Theoretical knowledge of nurses at a public hospital on cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In: J. Bioscience. MG. Uberlândia, 2013, p.1395-1402.

ZANINI J; BIRTH ERP; DCC BAR. Cardiac arrest and resuscitation: knowledge of the nursing team in the Intensive Care Unit. Rev. Bras. de Intensive Care, Santa Catarina- RS, 2006. Available at <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbti/v18n2/a07v18n2.pdf. P. 143-147>. Accessed on 10/15/2016.

1Instituto Nacional do Câncer

2Força Aérea Brasileira

3Hospital Universitário Gafreé Guinle

4Instituto Fernandes Figueira