REGISTRO DOI: 10.69849/revistaft/ch10202408171128

Andrews Barcellos Ramos1; Gustavo Roberto Minetto Wegner1; Leonardo Erik Bohn1; Vinícius Lemos Menegoni1; Christian Pavan Do Amaral1; Luiz Paim Menegusso1; Darlan Martins Lara1; Renata Dos Santos Rabello1

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Studies on work and health in prisons in Brazil are rare. The existing scientific literature indicates that work in prison institutions can be a source of stress. Objectives: To describe the prevalence of stress in prison officers in the north of Rio Grande do Sul. Methods: Quantitative, observational study with a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical design. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) was used to measure stress. Results: 50 correctional officers participated. The prevalence of stress found was 96%. The male sample 78%, aged between 31 and 40 years (46%), white (82%), those who consume alcoholic beverages two to four times a month (40%), with complete higher education (56%), and the most active servers with (70%). Conclusions: The present study found high prevalence of stress, which may be associated with some characteristics of the worker (gender, age) or with the function performed in the prison system. The need for an approach focused on mental health among workers in the penitentiary system should be discussed, and an attempt should be made to improve the health of these professionals.

KEYWORDS: Mental Health; Occupational Health; Occupational Stress; Anxiety; Prisons.

INTRODUCTION

Brazil ranks third globally in terms of its prison population, with the United States leading and China following closely. Data from the National Penitentiary Department reveals that over 820,000 individuals are incarcerated, with approximately 670,000 in physical cells and over 140,000 under house arrest. Despite these figures, the country continues to struggle with prison overcrowding, which stands at around 54%.1

Regarding the prison system in Rio Grande do Sul, data from the Department of Security and Penal Execution of the Superintendence of Penitentiary Services highlight that 42,573 people are serving some sentence in prisons in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. This number represents an amount of 40,423 men arrested and 2,270 women.2 Of this number, the Regional Prison of Northern Rio Grande do Sul, which has a capacity of 307 places, currently has a prison population that exceeds 600 prisoners in the establishment.

The profession of state prison officer is regulated by law 9.228/1991. It has as its attributions the services of surveillance, custody, and custody of prisoners, being classified as a life-threatening job.3

The present study examined the prevalence of stress among prison officers in a facility in the northern region of Rio Grande do Sul. Given the profession’s inherent stressors, such as constant pressure and demanding conditions, it’s not uncommon for professionals to experience physical and mental symptoms over time. This exhaustion can manifest in various ways, potentially leading to the onset of diseases that directly impact the lives of these workers.4

Given this perspective, this research sought to analyze the prevalence of stress in prison officers of a prison in the north of Rio Grande do Sul.

METHODS

This quantitative, observational study, with a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical design, was carried out between March and June 2022. The Regional Prison, located in the north of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, currently has 56 agents in penitentiaries who work directly with inmates. The study aimed to include all prison officers working in the selected prison. Between March and April 2022, the criminal servants received the interviewer at their workplace, being invited to participate in the research. Visits took place weekly on alternate days and times to guarantee access to all agents. Individuals who answered and returned the correctly completed questionnaires were included in the study. When considering the entire target population, the response rate was 89.2%.

The applied instruments consist of a questionnaire with the following independent variables: a) sociodemographic (age, gender, self-declared skin color, marital status, income, education, religion); b) habits and customs (use of alcohol, tobacco, and level of physical activity. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire-IPAQ short version was used to verify the level of physical activity. It consists of six questions that estimate the frequency (days /week), duration (minutes/day), and intensity of the individual’s physical activity during a “usual” week, both in occupational activities and locomotion, leisure or sports practice (moderate and vigorous intensity) and physical inactivity.5,6

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) was used for the stress outcome. It is a scale with 14 questions. The participant chooses a numeric option ranging from 0 to 4 (0=Never; 1=Slightly; 2=Sometimes; 3=Regularly; 4=Always) for each question, referring to the degree to which individuals perceive situations as stressful during the past month. The scale is composed of positive and negative responses. The sum of the scores obtained in the questions provides a result that can vary between 0 (no stress) to 56 (extreme stress). It was used as a comparison parameter that the tolerated level of the Perceived Stress Index is between 25 points; above that, it would be a more worrying stress index.7

The data were extracted in a spreadsheet format of the Google Forms application. These were converted to a format compatible with PSPP data analysis software (free distribution). All statistical analyses address the distribution of absolute and relative frequencies of the independent variables and prevalence with IC95 of the stress outcome.

The analysis of the distribution of the dependent variable (stress) was verified using the chi-square test, using a significance level of 5%.

All participants signed the Informed Consent Form (TCLE), agreeing with the aspects involved in the research. The instruments for data collection were self-completed, and two trained researchers carried out the collection. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Fronteira Sul (UFFS) and by the National Research Ethics Committee (CONEP) with opinion number 5,220,618.

RESULTS

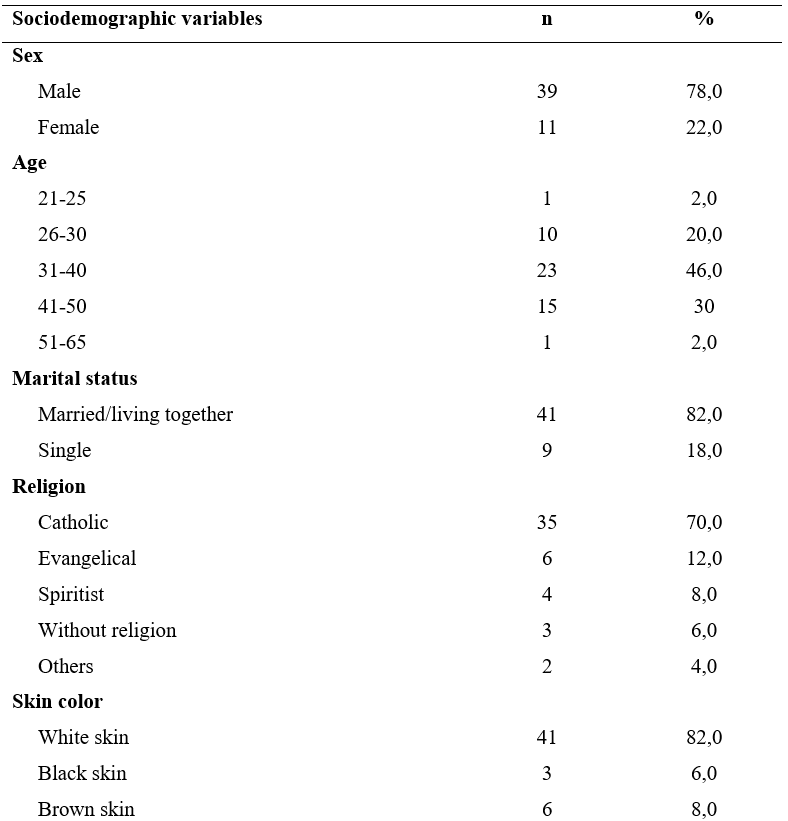

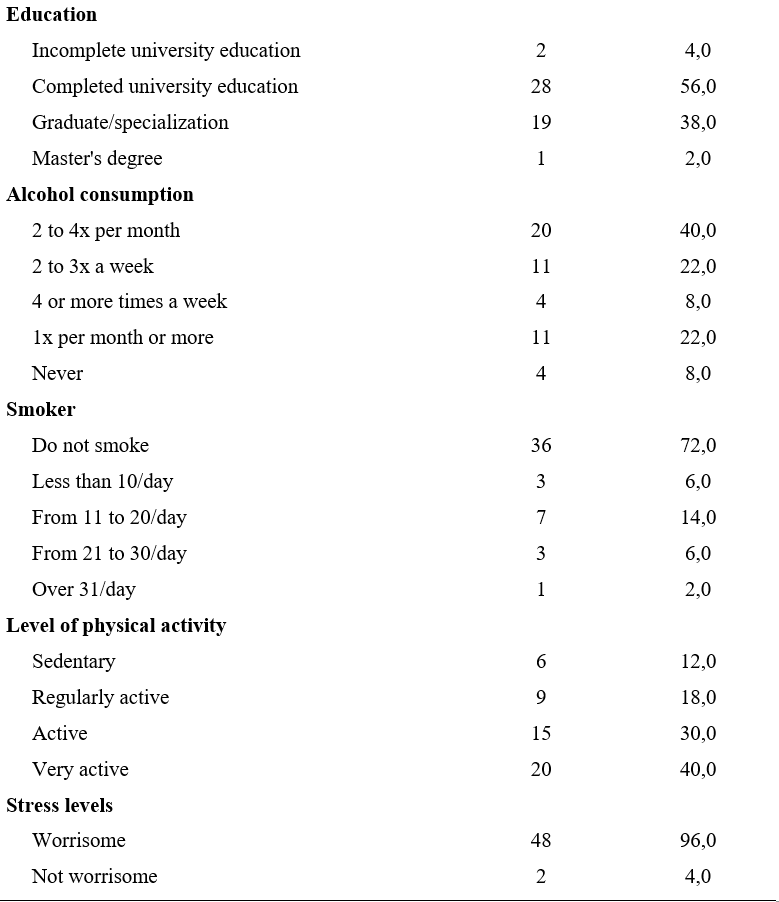

The total number of workers included in the study was 50. Sociodemographic data revealed that the average age was 31 to 40 years. Most are white (82%), male (78%), and live with a partner (82%). Per capita income ranged from R$7,001.00 to R$9,000.00 for 34% of respondents. The vast majority were Catholic (70%) and had completed higher education (56%). Regarding habits and customs, there was a prevalence – of those who drink 2 to 4 times a month (56%) – and a high prevalence of non-smokers (72%). Regarding the level of physical activity, the prison officers are active and very active in (70%) of the sample. However, with 96% (n=48), the study showed a high prevalence of stress in prison officers (Table 1).

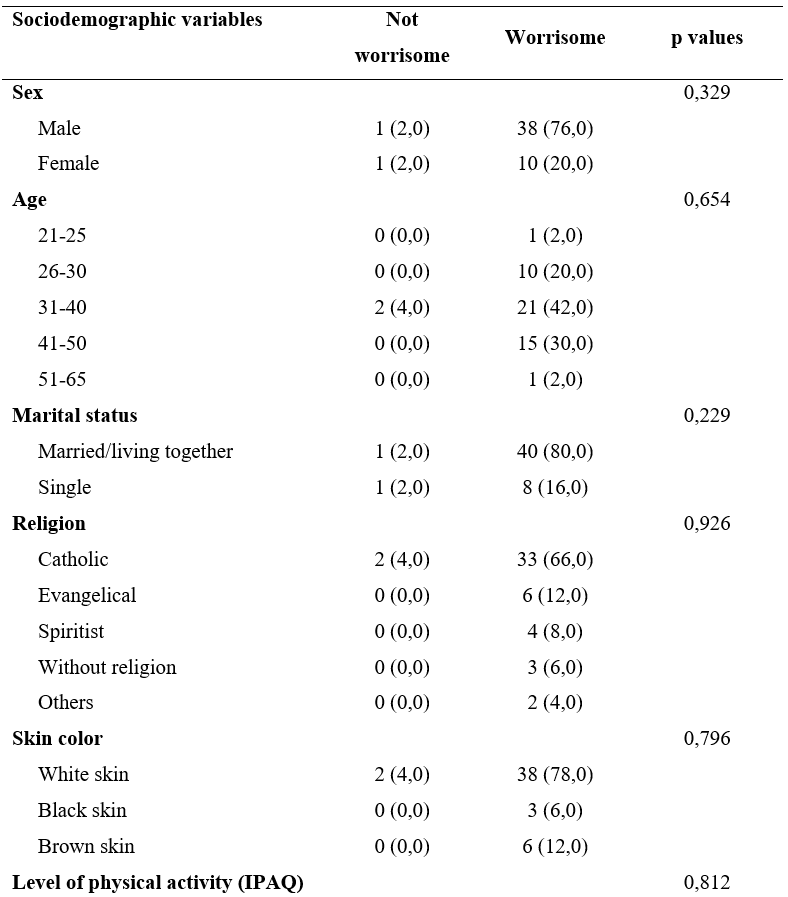

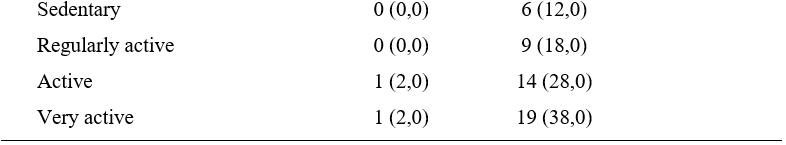

In table 2, on the distribution of stress according to associated factors and in relation to sociodemographic characteristics, no significant results were obtained for sociodemographic variables and habits and customs in this research. Most of those with a worrying level of stress are male, between 31 and 40 years old, white, live with their partner, and are Catholic.

DISCUSSION

When it comes to correctional officers’ work, their skills and personal integrity are crucial for ethical and professional conduct. Since 2014, in Rio Grande do Sul, this entails holding a complete higher education degree in any field, alongside successful completion of physical and psychological evaluations to ensure they meet the basic requirements for the role. Following approval, they undergo training to develop the necessary principles, personal and professional skills, and technical aptitudes, enabling them to excel in their duties within the prison system.8

We recognize that certain professions inherently carry factors contributing to stress emergence and development. Continuous exposure to danger, heightened alertness, and pressure within hazardous and unhealthy work environments serve as significant variables for the onset of stress symptoms.9

Based on the data collected in this study, it was observed that the majority of prison officers at the research site, comprising 96 %, exhibited a concerning level of stress. Remarkably, these stress levels surpassed those recorded among doctors (20%),10 nurses (21%),10 and military police officers (22.48)11, professions similarly subjected to high-pressure environments.

Globally, the profession of correctional officer is regarded as the second most dangerous, carrying significant risks to life and exposure to unhealthy conditions. A survey conducted in the United Kingdom analyzed the 20 most stressful professions, highlighting that correctional officers comprise the highest number of individuals experiencing stress.12

In a survey encompassing over eight hundred penitentiary employees exploring alternative roles within prisons, a staggering 72.75% reported their work as highly stressful. Additionally, 310 individuals expressed feelings of anxiety, 272 noted changes in their sleep patterns, 263 reported symptoms of myalgia, and 243 described feeling mood alterations, agitation, and heightened irritability.13

Regarding military police officers, a study involving 264 police officers from a state capital city in the Northeast region of Brazil revealed that 47.4% of these officers experience stress.14 Another study focused on professionals in public security, assessing the occupational stress of civil guards in a city in the Southeast region of Brazil. It found that 44.4% of guards exhibited a significant level of stress, which was lower than the prevalence observed among prison agents in our study.15

This outcome is indeed concerning, particularly considering that prison officers undertake a highly risky and crucial role in maintaining legal order within the country. The prevalence of stress among the majority of participants underscores the gravity of the situation. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the prison environment itself can significantly contribute to this stress, given the inherent psycho-emotional burden associated with it.9

During the period of data collection, it was observed that, in the environment, the agents are in constant vigilance and with a level of attention to all the movements that permeate the daily routine of the chain. In addition to paying attention to the cells, the prison officers carry out custody, escorting prisoners to hearings, medical and hospital visits, and transferring inmates to other establishments.

It is observed that most research participants are classified as very active or active (70%), a number close to the finding with the study performed in the Southeastern region of Brazil (74.1%).16

The results of our study mirror those of research conducted with military police officers from a state capital city in the Northeast region of Brazil. This study, involving 3,193 individuals, revealed similar patterns to those observed among prison officers. Notably, 86% of military personnel were non-smokers, comparable to the 72% of non-smokers among prison officers. Regarding alcohol consumption, 64.4% of military personnel abstained, a lower proportion compared to prison officers, with 92% reporting consuming alcohol at least once a month. However, there was a discrepancy in regular physical activity levels, with 62.1% of military personnel reporting a lack of regular physical activity, contrasting with our study’s finding of 70% of prison officers being active or very active.14

Given the data that the prevalence of stress in this professional group was very high, it is necessary to add that the mental health of the prison officers can influence the work profile of the convicts and their relationship with the institution, the way they work, the preservation of the dignity and rights of persons deprived of liberty.17

Other studies corroborate the findings of this research; stress is one of the main pathologies associated with the work of penitentiary staff.18 In another work, it is pointed out that stress is the greatest suffering described by this type of professional.19 Other authors characterize other stress-related findings, such as sleep problems, depression, gastrointestinal diseases, and extreme tiredness.4

A limitation of the study was the reduced number of participants due to its single-prison setting. This highlights the importance of further research in prison environments. However, conducting such studies is challenging, given the complexities of entering a security establishment, which involves daily routines of prisoner movement, safeguarding, and maintaining public order. Despite these challenges, this research remains relevant and underscores the need for more comprehensive studies in this field.

This research concludes that the evaluated prison officers exhibit a high prevalence of stress, indicating their vulnerability due to working conditions. Consequently, further studies should be pursued to understand and address this issue, emphasizing the importance of implementing public policies aimed at reducing stress levels among them. Correctional officers often go unnoticed and underappreciated by society, working with a population facing discrimination. This profession inherently carries a heightened level of stress, as identified in existing literature, posing risks not only to mental health but also impacting social, family life, and professional performance.

DISCLOSURES:

The main author declares being employed since 2021 as a correctional officer at the institution where the research was conducted. Ramos did not participate in the completion of the questionnaire.

The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1 Brasil, Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública, Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. 2021. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Apr 8]. https://www.gov.br/senappen/pt-br/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/segundo-levantamento-do-depen-as-vagas-no-sistema-penitenciario-aumentaram-7-4-enquanto-a-populacao-prisional-permaneceu-estavel-sem-aumento-significativo

2 Superintendência dos Serviços Penitenciários (SUSEPE). [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2022 Apr 8]. http://www.susepe.rs.gov.br/capa.php Accessed April 8, 2022.

3 Lei Ordinária 9228 1991 do Rio Grande do Sul RS. [Internet]. 1991 [cited 2024 Feb 19]. https://leisestaduais.com.br/rs/lei-ordinaria-n-9228-1991-rio-grande-do-sul-cria-o-quadro-especial-de-servidores-penitenciarios-do-estado-do-rio-grande-do-sul-e-da-outras-providencias

4 Jaskowiak CR, Fontana RT. O trabalho no cárcere: reflexões acerca da saúde do agente penitenciário. Rev Bras Enferm. 2015;68:235–43.

5 Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam T, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:115.

6 Matsudo S, Araújo T, Matsudo V, Andrade D, Andrade E, Oliveira LC, et al. Questionário internacional de atividade física (ipaq): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no brasil. Rev Bras Atividade Física Saúde. 2001;6:5–18.

7 Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

8 Administração penitenciária : uma abordagem de direitos humanos : manual para servidores penitenciários in SearchWorks catalog. [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2024 Feb 19]. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/5987495

9 Molina C, Calvo EA. Doenças ocupacionais: um estudo sobre o estresse em agentes penitenciários de uma unidade prisional. ETIC – encontro iniciaç científica – ISSN 21-76-8498. 2009;5.

10 Leonelli LB. Estresse percebido em profissionais da atenção primária à Saúde [thesis]. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2013.

11 Paredes DS. Nível de Atividade Física e Nível de Estresse de Policiais Militares do 16o BPM de Santa Catarina [monography]. Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2012.

12 Cooper CL, Davies-Cooper R, Eaker (Lynn Hamilton). Living with stress. Penguin Books; 1988.

13 Bastos FB, Paixão GSS, Baul MBS, Salles WA. Atenção psicossocial do servidor penitenciário. Documento apresentado no VI Congresso Consad de Gestão Pública, Brasília, DF.

14 Costa M, Accioly Júnior H, Oliveira J, Maia E. Estresse: diagnóstico dos policiais militares em uma cidade brasileira. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007:217–22.

15 Costa AJD, Froeseler MVG. Atividade física e estresse ocupacional entre profissionais da guarda civil municipal de sete lagoas (GCMSL). Rev Bras Ciênc Vida. 2018;6.

16 Bonez A, Moro ED, Sehnem SB. Saúde mental de agentes penitenciários de um presídio catarinense. Psicol Argum. 2013:507–17.

17 Brito LJ de S, Murofuse NT, Leal LA, Camelo SHH. Cotidiano e organização laboral de trabalhadores de saúde em presídio federal brasileiro. Rev Baiana Enferm. 2017:e21834–e21834.

18 Moraes PRB de. A identidade e o papel de agentes penitenciários. Tempo Soc. 2013;25:131–47.

19 Tschiedel RM, Monteiro JK. Prazer e sofrimento no trabalho das agentes de segurança penitenciária. Estud Psicol Natal. 2013;18:527–35.

TABLE 1

Table 1 – Description of the studied sample. Prison in the north of Rio Grande do Sul, 2022 (n=50).

TABLE 2

Table 2 – Distribution of stress prevalence according to sociodemographic characteristics. Prison in the north of Rio Grande do Sul, 2022, (n=50)

1Medical Department, Federal University of Fronteira Sul (UFFS), Passo Fundo Campus, Brazil